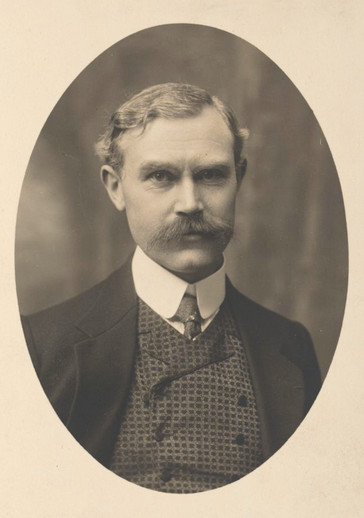

Albert Mockel (1866-1945)

What follows is the first English translation of Albert Mockel’s Stéphane Mallarmé: Un Héros (Édition du Mercure de France, Paris, 1919).

I

The name Stéphane Mallarmé conjures up an artist and a poet, and a philosopher who, even in casual talk, was the most discerning of critics and aestheticians. Others will speak of the man they knew, dissect his art, so noble, harmonious, and precise, and his thought, which he seemed, at least outwardly and deliberately, to pare down and condense, as though to sharpen its piercing strength all the more. Here, in discussing his work, I want to draw out two twin facets from this distinguished figure; to explore the meaning it offers us and, along the way, to recall the mental fortitude we owe to Stéphane Mallarmé, a true representative and a hero.

It may strike one as odd to bestow the first of these qualities upon a personality as singular as his, whose example was meant only for the elite of elites. And yet, Stéphane Mallarmé embodies for us one of life’s highest stances, because he was the unbreakable witness and the willing hostage to a quest for humanity and the human spirit. And the decisive action he set out to take was to present, whole and undiluted, the living figure of the Poet to those dismissive of poetry, and the image of absolute Beauty to an era devoid of glory.

In the age of our classics, beauty flowed abundantly across France; the poet’s task was simply to convey human greatness through his written work. If he wasn’t a noble lord, he lived meagerly, enriching the booksellers or scraping to secure the pension he needed to survive. Some of these great men were almost like servants, yet they reflected, in some measure, the courtly ideals; back then, one protected others and was protected in turn. This was a decline from the previous century, yet still an improvement over the Middle Ages, when poets, often despite themselves, were little more than wandering vendors of belles-lettres. Skipping over the 18th century, where poetry, if represented at all, was largely confined to publicists, we arrive at Romanticism and a lyric rebirth; suddenly, a new vision of the poet burst forth with a kind of splendid upheaval. For the rare few, it was Alfred de Vigny’s noble dream; for the masses, Musset’s charms; for all, it was the eloquence of Lamartine and the social force of Victor Hugo. The figure of the poet emerged, miraculously whole, from this triumphant moment. It was as if it aimed to realize and nearly succeeded in achieving the type of the great Greek singers—whole men—and of an age in which Pericles excelled in matters of intellect, Euripides competed in the Eleusinian games, and young Sophocles presented the citizens of Athens with the harmony of his bare form. True, each of these figures only partly fulfilled this ideal, and here, political action took the place of athletic contests. But for the Romantics, the poet—a complete man—was to command the assembly of the chosen as well as sway the hearts of the multitude, much like the role Plato envisioned for philosophers in his Republic.

This regal stance, abruptly taken on, could not last; having been improvised, it carried within it a trace of charlatanism, something elusive yet unmistakable that could tarnish the dignity of art. For all its faults, it was perfectly suited, like the grand orations of the Revolution, to the time in which it arose; yet it could no longer hold in the years that followed.

The Third Republic had decided to carry on without beauty. “No masterpieces, just a good average—that’s what our democracy needs,” remarked President Grévy as he strolled through an art exhibit. Positivism was in full sway; science, following German methods, pushed its own short-sightedness to an extreme. Metaphysics was scoffed at; philosophy was tolerated—but only just, for the sake of morality; and the era hailed practical inventions—all things that Contes cruels, Claire Lenoir, and La Révolte mercilessly satirized. They had shown a cool, distant respect to the noble Leconte de Lisle—out of modesty, in respect for memory, as if tossing a coin to a generation now past. They still honoured, without any real passion, and for a few sentimental pages, a most dignified yet poorly gifted lyricist: Sully-Prudhomme. But true fame was set aside for the lowly work of a Coppée. Heredia, the prince of an elite, would have starved if his art had been his only means. With genius to spare, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam knew nothing but hardship throughout his life. The most noble minds, like Dierx and Mallarmé, could indulge in lyricism only in the brief moments free from unrelated toil. Poets who wished to live life fully sentenced themselves, like Mendès, to the drudgery of journalism; and I name only Mendès because he, at least, found a way to elevate it.

Two men, however, rose to offer society—whether directly or by contrast—the emblem of its fault. One, as Stéphane Mallarmé pointed out not long ago, was the pauvre Lélian, Paul Verlaine. He offered the sorrowful figure of poetry, cast out from joy; he embodied its suffering, much like a vehement and tragic ecce homo. The other—Stéphane Mallarmé himself—took a higher stance, one akin to the loftiness of his thoughts.

The Romantics imagined the poet as the epitome of generosity, the man who would never fall short of any truly noble task. It seems that Stéphane Mallarmé took it upon himself to make this ideal a reality—but he did so without ever leaving the realm of intellect. The poet’s role is not to engage in external action; his duty is meditation: a meditation that embraces all things. It fears no necessary act, yet, beyond the pages of the book, it holds them all in potential. The soldier affirms his identity as a soldier through the sword, defending us all; the poet acts through the book, expressing us all within it. Now peace has arrived, the battles are far behind, and thoughts are turned only to the struggles of “business.” The sword rests dormant in its scabbard. But secretly, the military leaders are gathering to plot the plans for the next victory. It is as if, one might say, there are certain times when thought settles or sleeps. These times turn away from poetry, or at best, accept it only in its least noble forms. In such times, the poet turns to more mysterious words, to avoid the temptation of debasing his art. Yet, to those who can understand him, he will confide the secret of a heroic soul and the seed of future glories.

This, I believe, is the thought of Stéphane Mallarmé. Of the poet, whom he saw cast aside or despised, he revealed—without bitterness—all the simple grandeur, all the dignity; and always, though ever more distantly, he offered to the wayward crowd the image of that Beauty which they carry within themselves, but which they either disregard or reject. This is what his hermetic and distant art guarantees us—separated from the multitude not out of disdain, but in line with the duty he placed upon himself. It is not, as some may have believed, a fierce isolation. Rather, it is a solitude defended by the unwavering strength of a faith that is, in equal measure, a form of logic. Here, you won’t find the familiar revolts of Barbey d’Aurevilly; instead, one finds an infinite and serene sadness, one in which the pride of voluntary resignation can be read clearly.

There is no trace of vanity here, nor even the sudden eloquence of pride when it makes its appearance. Certainly, like all the truly great—those who have mastered themselves—Stéphane Mallarmé must have had that deep, vital instinct that leads some men to the hidden heart of their being, teaching them their own worth. Call it pride, if you will, because they reflect on the power they have gained; but just as much, it is humility, for they measure it as they contemplate it, comparing it to the ideal: I mean, to that future form, that superior image of themselves, where what still lies incoherent and unfinished within them would appear—at last—perfectly ordered.

Certain altitudes can only be scaled by that very pride. It’s the snow—cold, pure, and radiant—on which one steps to climb higher. But it soon melts in the warmer regions, blending with the mud in the plains; only a memory remains of it. Stéphane Mallarmé kept his pride concealed, for he was well-versed in every mental grace, even in the art of effortless nonchalance. With all the power of his intellect, he embodied the very essence of that power. His outward appearance was one of simplicity, directness, and even a touch of familiarity, completely at odds with any pretentiousness or dramatic flair. Yet, beneath it all, there was a silent protest, a quiet awareness of a right that had gone unrecognized.

Such are the tragic depth and emblematic nature of his work. It strikes us as painfully human, and present in the sense Goethe meant when he spoke of the word. Through its stark contrast—and just as much as the life of its creator—it stands as a representative of a particular moment in the history of letters.

II

If I now turn my attention to the internal structure of this work, I will find the same lesson. To its forgetful but beloved race, Stéphane Mallarmé sought to present the image of the perfection it holds within. What it could read in his verses was its own genius, elevated to a sublime level. But it failed to see, and so the poet withdrew into a solitude harder to access, there to sing a truth far more absolute. It was a reorientation of the centre of aesthetic sensibility. We perceive only relative truths, and those that are the most relative open up more easily to us, as they are bolstered by an immediate example; we enter them through the senses, in the forms they give us, and through the feelings that lead us to them via memories. Pure intellect only comes into play afterward, as though to complete the understanding through comparison. The less relative a truth is, the more difficult it is to grasp. As we draw closer to the absolute—perhaps forever sealed off—the labour of the intellect intensifies; the senses and sentiment fall further apart in their responses, offering fewer comparisons, as though steps were missing.

The poet gradually scaled back the sensory elements in his work1. This, some have criticized. Yet, in doing so—though certainly pushing them to their extreme—he was, in fact, harking back to the most ancient traditions of French letters. Romanticism, born out of foreign influences like the Pléiade in earlier times, had filled Poetry with a rich array of colors, forms, a more resonant harmony, and a new wave of emotion. But the French tradition is more economical with external means, and is less sentimental than it is grounded in logic. — Stéphane Mallarmé’s art is, above all else, a matter of logic.

“I call what is healthy classical,” Goethe once remarked, “and what is sick, romantic.” He had in mind the unity, structure, and natural harmony of great, perfected works. Yet within the strange, often formless attempts of German Romanticism, there was already something of what would later be known as decadence. A kind of art in distress, if you will—this is what Baudelaire pioneered in our literature—a neurotic art where each detail brims with its own life, sometimes even breaking away from the whole, like an intricate portal blossoming from the side of a cathedral. These are the eerie flavours, the rich, vivid, and deathly hues that Théophile Gautier celebrated in his preface to Les Fleurs du Mal.

I deliberately make these comparisons, to challenge the old prejudice that lumps together the deliberate, ‘constructed’ symbolic art of Stéphane Mallarmé with a type of art it fundamentally denies. If we call classical a work governed by thought—a rigorously logical creation that speaks to the intellect, unfolding in meticulously measured proportions, drawing its strength from their coherence—then Stéphane Mallarmé’s work is indeed classical.

Classical, yes; yet certainly not in the precise image of the 17th-century masters. They would hardly have recognized their own method in Mallarmé’s work, transformed as it was through an unyielding rigour, and might well have been perplexed by the forms he employed. In the world of art, a genuine artist knows no beginnings anew. This artist had experienced Romanticism, had known and cherished Baudelaire, drawing in the potent and bittersweet fragrances of his illusory bouquet. — Every new beauty, once unveiled, is eternally alive; its reflection mingles with the countless others already contained within the vast, clear, ever-shifting waters that carry eternal Hope through the generations of humankind.

Since Baudelaire, the demands on poetic form had risen. His work illuminated the subtle depths of poetic expression, and so it came to be crafted with finer threads, woven together with stranger, more exotic silks. And to this classical framework of old, Stéphane Mallarmé added, quite naturally, an embroidery of fine detail that the grand century had never known; but rather than outlandish, sultry blossoms or strange, otherworldly beasts brought forth by The Flowers of Evil, he traced light, slender threads over his tense-strung stanzas, sketching ethereal forms—lilies, swans, and nymphs in watery scenes. A graceful, restrained decoration set against the purest white imaginable: Jean Goujon might have been captivated by the supple grace of these water spirits, in whom the dream of Fontainebleau finds its fullest expression, while the architect of Sainte Chapelle would have recognized, in their delicate fragility, the airy lines of a celestial ornament. Here lies the delight of French grace, this fancywork where even the sublime stays exquisite. The design is traced with unmatched restraint, and the marvel of this art lies in how the colours are all there, fully contained, waiting to be discovered through transparency, without any relief to betray their presence.

Often, it’s a single image that stirs the poet’s hand. The poem springs up as its natural interpretation, circling back to touch that image again, revealing in passing a few sister images—always with a subtle gesture, one that gestures from a distance, never dwelling on any one thing, content to let the image be glimpsed through the art of suggestion.

As for the musicality of his verse, it would be difficult to argue that it ever drifted from the strictest of French traditions, reaching back to the pastourelles of the eighteenth century, or even Rutebeuf himself; Racine, too, stands as proof that it was not altogether ignored in the grand siècle. In Stéphane Mallarmé, it takes on an unmistakable clarity, no longer left to mere chance but shaped with an almost unmatched assurance. Fluid and full of delicate shades, restrained to the utmost, his verse says everything through its pliant harmonies. So crystalline that it sometimes seems to vanish in its own perfection, it’s a stream gliding over things; the eye senses it by the freshness it leaves behind, diving unknowingly into those transpicuous depths.

Shall I speak to the nature of emotion in Stéphane Mallarmé? At first glance, it may indeed seem almost naïve to try to link it with what we call the genius of France. Emotion, after all, hardly recognizes nations or races; it is simply, profoundly human. Yet it has taken on different forms in literature, evolving with the times as much as with individuals. The Romantics—if we set aside Vigny—tended to exaggerate its expression, drawing it out. In classical times, it had seemed cooler, almost held rigid by a certain majesty or concealed within the stately folds of an eloquent cloak. The poet of Hérodiade, following the somewhat unruly fervour of 1830, returns to the antique “nothing in excess.” The passion of movement matters to him less than its precision. His emotion—which never lapses into mere sentimentality—seems, rather, held back by sheer force of will or half-hidden as though from a kind of pride. Rarely does it break out in a direct outcry:

To flee, far away! Flee…

or in that famous line:

The flesh is sad, alas, and I have read all the books2.

But the soul, which had so freely given itself over, quickly reclaimed control, and one might say it now holds, with quiet dignity, the secret of the pain and indignation it had been about to express. Or rather, its purity seems to have risen. It rises above the world around it, now floating over everything, observing as a disinterested spectator, with the tranquillity of contemplation. Yet the emotion lingers. It will no longer be openly voiced, for it must not, at this point, usurp the place of a loftier idea. Instead, it seeps into the poem like a subtle fragrance, one that’s troubling us, both entrancing and elusive. More tragic and potent for being silent, it extends its reach. It is no longer a single individual suffering, as in the case of the Romantic individualists; now, it is the entirety of humanity speaking through the voice of one.

And let us observe once more: the classics revelled in expressing broad, sweeping emotions. Here, however, the emotion of a solitary dreamer, held back by his own sense of dignity, becomes something universal.

I would love to pause and linger over the images and the music of Stéphane Mallarmé, and the exquisite emotion they contain. They are like translucent stained-glass windows, casting light upon his work while imbuing it with colour. Through them, we can access the hidden depths of a Beauty that seems more alive, shining with the clarity of precious stones. But from the dry, analytical standpoint I have chosen, it is the architectural structure of this work that I must focus on.

Of the three foundational elements of art—form, emotion, and thought—Stéphane Mallarmé chose the most austere one as the organizing principle for his poems: thought. It serves as the measure by which all things are judged, the living centre to which all things ultimately point. Like the classics, it belongs to the broadest order, but—wherever no trace of allegory remains—it emerges naturally from an image that was its very origin, and that still speaks as its resonant symbol.

The poet discovers, in nature—which he seeks to explain—a truth to exalt; this becomes the initial spark of his song, or, if you will, the reason to shatter the silence. But from this moment onward, everything is arranged according to his own design. Once the vision or life’s truth has been unveiled, its meaning must be steered toward the related ideas it is meant to awaken, and then it must be pressed into carefully chosen images. In this way, reasoned will takes on a distinct role; its stance is commanding; it orchestrates everything, under the rule of logic and sovereign thought.

Here, nothing exists but a sequence of facets of eternal truth, as the poet has envisioned it. There are no preliminaries in this rigorous art. The images themselves are fundamental, appearing less as mere decoration than as a kind of refined verification within the very things they depict. The idea ascends, with a purity of sound, only encircled and supported by all the harmonic ideas it is destined to evoke3.

Strictly governed by thought—intellectual before it becomes sentimental or engages the senses—the work of Stéphane Mallarmé truly belongs to the oldest tradition of French art. The elegance of his lines alone made it clear, with their compelling charm. In fact, I know of only one master in our time—M. Anatole France—whose writings, side by side with Mallarmé’s, bear witness to the untainted French tradition. And yet, France has failed to recognize its own image in these verses that assert its beauty!

Through its majestic ease, the balance and precise harmony of its proportions—one might even say through a kind of pure simplicity, revealed within the form beneath the complex swirl of ideas—this work brings together some of the finest qualities of the classics. And yet, the corrupted classics that still exist have despised it. Could it be because the sobriety here is not dryness, because the majesty is not rigidity, nor the simplicity a form of poverty? One wouldn’t dare deny it without irony. But beyond the reasons we can surmise, and which I will attempt to explain, it was, as we now understand, because a mind too logical had pushed their own method to its extreme consequences, and they deemed it thus perverted.

III

The main criticism, and the one shared by all, is that Stéphane Mallarmé’s art is obscure. I cannot argue with this: the obscurity is undeniable. He must have been aware of it himself, and certainly, it was not without a hidden purpose that, in representing the Poetry of an era indifferent to poets, he raised its image so high, placing it beyond the immediate reach of the crowd, who would never have seen this beauty had it been right before their eyes. I wouldn’t dare say that he was wrong.

The poet’s role is to give even to the ungrateful; and even if they toss in the first coin, or the tenth, or the twentieth, because by the hundredth coin they might just realize that the image is pure and that the coin is gold. — Oh no! Stéphane Mallarmé would reply. It’s better to share, among the few who understand its worth, a treasure that the masses completely misunderstand, and to deny the crowd a generosity it would not grasp; better that than to trade this true treasure for counterfeit riches, and to hand out worn coins that are accepted by mistake, or worthless metal that can’t postpone misery by even a single day.

“There are, in the world,” says M. Paul Adam, “seven or eight mathematicians of extraordinary intellectual power. No one else can solve the problems they set for one another. And yet, these mathematicians are not looked down upon!” The argument is both ingenious and undeniably persuasive. But I don’t think we should settle for such a limited conclusion. The page that is obscure today may, tomorrow, shine brightly.

Examples abound, and history proves that appreciation for artistic works shifts from one era to the next. Hard to believe, but Gustave Planche once faulted Sainte-Beuve for a lack of clarity… But let’s call on even greater witnesses. Bach, famous in his day, fell into obscurity afterward. Only a few of his lighter pieces stayed known, while his cantatas were forgotten entirely; his harpsichord works, concertos, sonatas, and toccatas came to be seen as mere exercises in will—a kind of musical mathematics with meanings that had been lost to time. Yet, as revealed by time itself, they are indeed masterpieces. Beethoven’s last quartets, too, were dismissed as unintelligible when they first appeared, and his Ninth Symphony was once written off as the work of a lunatic. I think this is because, in those extraordinary compositions, as in the art of J. S. Bach—or indeed in the work of Stéphane Mallarmé himself—thought takes precedence over all else. With Bach, this thought is serene, so luminously clear that it slips past distracted eyes; in Beethoven, it’s complex, revealing the noble restlessness of a soul that was never fully at peace. In both, thought seems to eclipse feeling. Perhaps humanity is simply so unused to encountering pure thought that it fails to recognize it when it stands alone. And do we even need to mention Richard Wagner? As is all too well-known, not so long ago, his symphonic brilliance was derided as a chaotic darkness.

It is no mere chance that I have chosen these three poets of music. Not only because they are the greatest, embodying the full sweep of our spirit—its mystical aspirations, its deep contemplation of human fate, and its heroic ambition to overcome it. It is also because each of them stands as a deliberate creator, a visionary by choice; and because within each of them, one finds something that mirrors the poet of Hérodiade.

The true place for admiring Mallarmé’s heroism is in his life itself, for he succeeded in shaping an art uniquely his own; yet his poetry, too, bears this heroic spirit—restrained, it’s true, and almost veiled, but still visible. What one perceives is a HEROIC IDEALITY, a brilliance that shimmers in the Swan’s pure indignation. Mallarmé embodies a striking purity, a radiant whiteness that evokes the very essence of Parsifal and Lohengrin, those champions of the ideal. Here as well appears Beethoven of the late quartets, with the intricate depth of his thought and that powerful inner logic of “development”—not the straightforward logic of Bach, which tightly binds thoughts in unbreakable chains, but a more inward logic, born of intuition, capturing ideas by their hidden cores to unite them. This profound logic, which perhaps Lassus and Palestrina dreamed of, Beethoven brought into music forever, and Mallarmé alone, thus far, has introduced it into literature. Then there is Bach himself, symbolizing perfect serenity; in him, it arises naturally, grounded in a faith in divine guidance. In Mallarmé, this serenity is won through self-mastery, by a stoic disregard for suffering. His is the transparency of an art so pure it seems to transcend earthly concerns; it is noble in line, its elegance soaring in slender forms, an architecture balanced with an almost miraculous precision.

Here, then, are indeed certain analogies. And I would add yet another, already mentioned above: that within the most beautiful and supposedly obscure part of Beethoven’s work—just as in the works of Bach, and as in Mallarmé’s—emotion, however powerful it may be, is intellectual before it is ever sentimental. Why, then, shouldn’t the poet, like those who were once dismissed, become the prophet of tomorrow?

And yet, there is something undeniably perplexing about it. Many verses, I confess, remained a closed book to me for a long time, and some still leave me disappointed. But what should I make of it if I return to certain poems among the most admired—and if I remember how I, too, once stopped here, unsure of their meaning… As soon as a stanza is fully grasped, it sometimes throws us off with its unmistakable clarity, leaving us wondering why it caused such discomfort at first. There is a riddle here, one I would like to solve.

What is it that causes this obscurity? I can sense several reasons, the first of which might seem trivial. Due to a scruple I find poorly justified, Stéphane Mallarmé, who in prose employed complicated punctuation, had chosen to abandon it in his poetry.

Let no one think this was merely a whim; such indulgences were not allowed in his art. It was the conclusion—perhaps an unfortunate one—of a perfectly logical line of reasoning. He saw poetry as the most intellectual form of music—and prose as incomplete music. So, he argued, punctuation must be added to prose, as it holds the “keys of discourse,” and prose needs it. But let’s not clutter the poem with unnecessary periods and commas. They disturb the eyes, interrupt the flow of the stanza, and above all, they strip the verse of its sense of absoluteness. Should we guide the intonations? — Music alone is enough, and will direct them by itself, in line with the flow of thought4.

I transcribe these arguments, though they have yet to persuade me. They reveal a scruple that verges on the obsessive. However, I must add that, to properly assess them, one must connect them to a series of very specific ideas I shall scarcely delve into here. The poet had given particular attention, with remarkable persistence, to everything—even remotely—related to the act of writing. The pen, the gesture of the hand that traces, as he explained, seemed to take on a life of its own; and, for instance, the inkstand, as clear as a conscience, with its drop of darkness lingering at the bottom…

He had the most subtle and ingenious insights into what a word, a phrase, a line, a blank page truly are. He explained them with a thousand reasons, paradoxical to the casual onlooker, yet profoundly meaningful from the poet’s perspective; all of them held a certain charm and offered the mind a rare kind of diversion. Small musings, some might call them, insignificant things… Perhaps. Stéphane Mallarmé believed that for an artist, the duty is to overlook nothing that pertains to his mental process, and that no concern is too small when it comes to creating Beauty.

But there are more serious reasons behind the obscurity of his verses than this. One of them, still external, stems simply from the idea we have of what constitutes clarity in verses. I mean, in beautiful verses. — Our readings are filled with illusions. The pages we deem truly thoughtful, the ones we find clearest, often seem so to us because of our mental limitations, which spare us the effort of truly engaging with them. We barely touch their shining surface, but that’s enough for us; and satisfied with this fleeting nothingness that only brushed against our fancy, we move on, unaware that the poet’s true vision and the mystery of his emotion remain hidden, from those of us who only linger on the immediate meaning of the words. The superficial reader who skims through Hugo’s poems quickly picks up the eloquence of the antitheses, or, in Lamartine, the melancholic romance, or if he flips through Baudelaire, the fiery essence of images he wasn’t expecting; but the true Beauty of those verses, what would lay his soul bare and leave him shuddering before an unrevealed God—this, he will never know.

In this rushed age of ours, you’ll often come across those travellers with round-trip tickets, hopping from city to city, crossing squares and streets, admiring the monuments, and then already making their way back to the station for the trains heading out. The city has shown them only its closed facades; but of what breathes behind those facades, of all the lives woven together with their heroism and their banality—of the customs of these people, their art, their prejudices, all the good and all the evil they have contributed to their homeland and the vast world—these passers-by have seen nothing, understood nothing: nothing but the lifeless stone that contains it all.

Yet the palace of Stéphane Mallarmé has no external display to distract or amuse the eye of the hurried traveller; nothing to seize his mindless glance. Its facade is simple and modest in scale; no colour screams at you, no ornament calls to the gaze. It charms only through its proportions, which are exquisite, yet do not impose themselves on anyone. It matters little that within there are rooms draped with rare tapestries, chambers filled with priceless treasures; the facade remained silent to the careless tourist. His train, no doubt, was calling to him, and he failed to notice the golden light filtering through the closed windows.

There’s no show of virtuosity in this poetry. The images, however plentiful, only shine to convey something. Everything in it is essential. For those who read, it’s nothing more than words that fall flat, much like those who hear only soulless notes in Bach’s Harpsichord or Beethoven’s Great Fugue.

This supreme discretion when it comes to the adornment of thought is, I must stress once again, the strictest and most classical French tradition, which a poet has carried to its furthest limits. What may seem most foreign here, however, is the reluctance to draw conclusions. But beyond the highest aesthetic reasons that justify this, it is imposed upon Stéphane Mallarmé by his estrangement and solitude. The exceptional man, whose thoughts express the problems of life yet has placed his voice outside the crowd, cannot address it directly, nor can he force it to heed his arguments. If he does wish to influence it, it will be through an indirect route, almost by accident. His goal—Art’s goal, in fact—will be less to convince than to gently persuade. He will not bluntly declare to these men what, being too distant from his beliefs, they would refuse to accept. But to a select few, he will suggest the truth, in such a way that it seems they have discovered it themselves, within things. As Carlyle says, “For a base eye, all things are vulgar.” But a truly beautiful soul will see the sign of Beauty everywhere.

“I do not place my thought like a statue in the public square,” the work of Mallarmé seems to tell us. “But I have shaped it as one, unified, discreet, and profound, like a mirror. Its ripple is true. Come, measure your dream against its reality; and depending on what you bring, its reflection will reveal either the full nobility of the human figure or the grotesque grimace of your own ugliness.”

The ordinary reader is left disappointed here. All his usual expectations are upended. He waits to be told, but instead, he is asked to think. The meaning of a poem isn’t laid out for him in painstaking detail; rather, in a radiant equilibrium, its vivid images are revealed. It is his own effort that is called upon, so that he may uncover, more elusive yet revived by a youthful clarity, the Idea that will soon stir within him the graceful apparition of his own soul.

Thus, within forms that aren’t precisely described but only hinted at, ideas gradually reveal themselves. In the heart of the princely palace where reflection calls us, they drift like translucent phantoms, with no sound to betray their steps. Though they make no claims, they hold sway alone in these enigmatic halls. Only by allusion are they ever spoken of. At times, it feels as if they have vanished altogether, as if some inattentive gesture broke the melody they hum. But there they are, the moment one thinks of them; one feels their undeniable presence, like a gaze that watches yet hides its eyes.

The reader, as I was saying, finds himself thrown off course. Yet what is asked of him is only to honour the innate genius of his own heritage. To capture the meaning of a suspended conclusion, to pick up on an allusion, or to catch what’s hinted at with a half-spoken word—these are qualities of the mind, subtle and refined, that are most truly French.

But what is allusion, really? It plays, with greater restraint, the same role as metaphor. The latter reveals the result of an unspoken comparison. Similarly, allusion hinges on the comparison of two ideas: one made explicit, the other assumed to be familiar, already present in the mind. In essence, it is nothing more than a more delicate kind of metaphor, one used among people whose thoughts move through the same intellectual spaces. Here, we assume a mental kinship between the reader and the author, who meet in this intimate circle of intellect, gathering like friends at a shared table—that of the Book. To Mallarmé, allusion is the very grace of poetry. Likewise, it is the grace of conversation itself—a small touch of confidence slipping between speakers, built on a shared heritage of knowledge, opinions, and assumptions that each believes the other holds.

Our forefathers believed that saying everything is the surest way to bore an audience. So, what peculiar paradox is it, then, that makes us reject mystery in poetry as something overly complicated, while we almost expect it in the lighter words tossed out for our fleeting moments of idleness? I think this holds the key to the puzzle. This aversion to mystery doesn’t merely stem from our well-known preference for clarity; rather, it reflects a disconnect between reader and poet. The poet, drawn to absolute beauty, voices only what he deems essential; anything beyond that seems to him a kind of redundancy, an ornamental distraction—a dead weight that drags down his flight. The reader, meanwhile, can no longer find in the poem’s solemnity what he once delighted in during the easy banter of a casual chat. He searches for answers but finds none close at hand, no ready echoes in his memory; his mind just hasn’t been trained for it. He is, in a word, “out of touch”.

Allusion, in conversation, is understood by everyone because all share the same social privileges—familiar scenes, common experiences with familiar faces, objects, and, often enough, the same readings. We rarely stray far from a familiar circle of ideas, and these ideas are seen in much the same light by everyone. Shared customs prompt shared words and gestures; incomplete sentences are effortlessly understood, creating that charming ease of feeling ‘among one’s own’ and recognizing oneself in others. — This is also the delight of the literary-minded reader, savouring the allusions within beautiful verses. Like a guest in an exclusive salon, he encounters ideas he knows well; he moves among them with ease, for this world is his own. Though the scope of these ideas is indeed vastly wider, most are old friends; and the allusions seem no less clear to him because, instead of leading to some petty gossip, they address his whole being, raising him up to the very threshold of beauty.

But when an unprepared reader stumbles in—if his mind isn’t attuned to poetry, if he’s tangled up in trivial concerns, or if he has little practice in reflection—he finds himself like a stranger, inadvertently drawn into an intimate gathering. All the other guests are familiar faces here, but he knows no one; he cannot catch the hidden meaning in the words that draw laughter or exclamations from those around him, and soon his discomfort becomes unbearable. Perhaps it’s his own fault, understanding nothing of what’s going on and having nothing to say. But maybe, too, there’s fault on the host’s side, for neglecting to look after his unexpected guest. Were this objection raised to Stéphane Mallarmé, he would likely have answered, “Why so? A stranger, yes, but I welcome him graciously. Yet, why has he not attended our concerts and spectacles, why has he not read yesterday’s book before joining our little circle? I cannot, for the sake of an unknown visitor, let this delightful conversation fall flat.”

The absolute art that Stéphane Mallarmé sought left him no room for any other approach. Furthermore, the use of allusion or the deliberate omission of a conclusion might, for the unprepared reader, add to the mystery of the verses; but this is merely an incidental factor. It undeniably drives away anyone who expects the lyrical verse to provide clear-cut sensations and neat conclusions—in short, almost the very opposite of poetry. For others, however, it is merely a fleeting veil. Every mind must learn to embrace the art of slightly parting its fluttering folds, and in doing so, there is the joy of a discovery that carries all the allure of a secret shared with quiet intimacy.

IV

Up until now, it was the artist who was to blame for the obscurity of the book—by which I mean its aristocratic nature. But there is, in fact, another reason for its existence, one that’s less known, and that concerns both the poet and the philosopher equally.

“No eye, however gifted,” as Carlyle says, “can ever exhaust the meaning of any object, no matter what it may be. In the most common human face, there are more things than Raphael will ever take away.” Now, this is certainly a beautiful statement, and it rings true. But it’s more Saxon than Latin. The southern genius, which the French belong to, has a fondness for generalization and classification. And because of this, it tends to isolate images and ideas into separate categories, rather than imagining them as tangled together. Its strength lies in seeing, in each thing, that single luminous point that pushes everything else into the shadows, revealing its concept in a way that’s decisive and unchanging. It’s quick to tell apart the essential from the incidental, but perhaps it overdoes it, separating them too sharply. Yet, the incidental is hugely important in poetry, which is no mere web of syllogisms; and no less important for the thinker, for those incidental ideas are but extensions of the main one and — I’d like to stress this — they link it with other ideas of equal weight. They are like the stretched or retracted filaments of neurons, the connecting threads between the cells of our nervous system when our consciousness stirs from sleep.

Unlike the French genius, which tends to simplify, Stéphane Mallarmé is chiefly struck by the complexity of phenomena. He has marvelled at how they interact with one another and the infinite variety of their connections, which his art uncovers in the form of a unanimous convergence.

One might trace the origins of this view of the world to the Greeks; even the idea of universal consistency, which underpinned Marcus Aurelius’ moral philosophy, is closely aligned with the notion upon which Mallarmé grounded his aesthetic. And yet, despite its roots in our ancient intellectual homeland, Greece, this vision seems to stand quite apart from the arts of France. From the Platonic doctrine, the French have mostly taken away the theory of Ideas, along with a tendency to view humanity as a series of fixed types.

Of course, one must not overlook either Victor Hugo or Baudelaire, whose poems are so rich in correspondences. Yet, in Baudelaire, there was a distinct desire for contrast, the deliberate intention of “not conforming.” With Hugo, these correspondences are primarily verbal, and we know how rooted the French are in this tendency toward verbalism. Something of it can even be found in Stéphane Mallarmé himself. He had not renounced “the worship of the word… which, beyond any doctrine, is simply the glorification of the race’s innermost essence, in its bloom, the language itself.” — Let us not be too quick to decide that this is a flaw: it may very well be the essential condition of style. For doesn’t the poet need to fall a bit in love with words, to bring them to life and know their full worth, just as the true painter becomes enamoured with colour or with the rhythm of a line?

I admit that there is a divergence here—and I don’t believe it’s essential to look for remote explanations. A superior individual overcomes, if need be, the tyranny of his moral surroundings and even that of his race, or he reshapes its inclinations. He possesses a mindset that is uniquely his own: sentimental in Lamartine, satanic in Baudelaire, elegiac in André Chénier… none of this is particularly French. The mind of Stéphane Mallarmé perceives an abundance of connections between things, and perhaps this is because his close study of verse has developed his sense of metaphor—which always implies comparison—to an extraordinary degree. That alone is enough for us. — But one could also add that this disposition in a poet’s mind is deeply revealing, a true sign of his time. Harmony within complexity is, indeed, a reality of our time.

I could expand on this point. There would be no shortage of examples to support it, from Wagner’s vision of the synthesis of the arts, to M. Vincent d’Indy’s methods and our return to painted sculpture, and all the way to the latest findings of the sciences. But it seems so self-evident to me that I will assume it already understood.

Mallarmé’s philosophy brings to mind an unexpected insight: it doesn’t necessarily rest on the idea of progress or evolution. At moments, a hint of doubt does arise:

Yes, I know that in the far distance of this night, the Earth

Casts a great, radiant, strange mystery

Beneath the hideous centuries that darken it less.

But this doubt is soon cast aside, yielding to the Dream, creator of all things, and the universe appears more like a still, circular mirror to the dreamer, echoing back images that are illusory yet full of meaning. Illusory, because nothing exists outside of thought; yet meaningful, if the outside world—the objective form of the self—calls forth hidden harmonies, as though measuring itself by its own shadow within life’s mythic echoes. An endless web of mysterious connections threads through all things, but this web is merely the reflection of another, woven in the soul of the contemplative mind.

In this way, we can understand Stéphane Mallarmé’s idea of the symbol: “Every existing object serves a purpose only if we see it… in other words, to represent one of our inner states; the array of traits it shares with our soul elevates it to the status of a symbol.”

When words flow harmoniously, they give their speaker a palpable sense of Life5. They form a mark of existence, the mark of an absolute that gathers the scattered emblems of the universe into a single, unifying presence. “Everything, in the world, exists to come together in a book6.” And yet, this absolute remains subjective, born in the mind that envisions a God contained within nature. But nature itself does not appear alive in the way Schelling would have seen it; nor does it hint at any ultimate purpose—unless we grant this sense to the image of chaotic incoherence, a reflection of our own disarray, an accumulation of shapeless material, awaiting endlessly the hand that will bring them into form. Outside of ourselves, the universe lies as the boundless domain of Chance. Every human act affirms the very chance it hopes to refute; in simply being realized, it borrows its means from chance. And yet, out of this chance, a world may burst into being7.

Whether or not there’s a contradiction here, I cannot say—it may well lie with me alone. For all its brevity, and despite its dryness where I sought above all to be clear, this account may contain flaws. I can only hope none are essential; but it is always risky to condense into a few lines a philosophy whose traces are scattered across poems. By allowing for some uncertainty here, I limit myself to specifying that the poet drew from an idealist Philosophy, one that wavers between Fichte and Schelling, and may even bring Berkeley to mind. “It is in illusion,” this philosophy says, “that we must search for truth; it is the sole reality, the only thing that concerns us. Truths are woven from intertwined illusions.”

For Stéphane Mallarmé, an idea never comes alone. Isolated ideas are mere abstractions. — Quite so. I’d like to add that, in real life, ideas always come as a broad, shifting current, where each element holds up the next. The single drop of water I might scoop from it no longer belongs to the flow; reduced to an inert droplet resting in my hand, it loses its connection to the great stream pulling the others along, and I cannot catch my reflection in it any more. It’s only by leaning over the moving stream itself that I can catch sight of the living water—water that moves with unstoppable force toward its destiny, or toward the sea.

I wouldn’t go so far as to say that French writers have only ever glimpsed ideas one at a time or that they have always isolated them from their complementary sister ideas. You can see this tendency in Les Caractères by La Bruyère or in Molière’s The Miser and The Misanthrope (a tendency even reflected in their very titles). Further examples come to mind: the guidelines set forth by Despréaux, Corneille’s single-minded heroes, and more still—but none of these define a strict rule. Yet the norm, right up until our century, has been to present ideas in sequence, whether in the novel, in drama, or even more rigidly in lyric poetry, where such a method remained the standard for a long time, even in other traditions.

As far as drama and the novel are concerned, this is clearly rooted in our preference for simplicity. As for lyric poetry, I believe it’s because it had not yet fully realized its worth — neither with us nor anywhere else.

If I define lyricism as the complete outpouring of a soul into the forms where it comes to know itself through their reflection, it is undeniable that its true realm lies in music, and its most perfect expression, the modern symphony. Nothing, in fact, is more complex than a symphony. One feels that a being presents the theme of its contemplation and embodies it; it plunges into sorrow and joy, uniting the voices of all nature in a final declaration. But this theme was never alone; it immersed itself in harmonies, encountered other themes that either challenged or supported it, and compared itself to its earlier, untransformed self when it emerged anew. — So, let lyric poetry move closer to this idea of the symphony. The deep emotion that drives it cannot be satisfied with a single object; rather, let it grasp the full breadth of life, let it feel the contrasting forces of what lifts it up and what drags it down, let it contain countless bursts of feeling, let it dive into its deepest centre and spring back from there toward the infinite — and only then will it achieve the sublime!

This is roughly the ideal that Stéphane Mallarmé aimed for in his last poems. However, he expressed it in a manner that was both severe and discreet, with an extreme economy of words.

The “complex actions” that the old Aristotle contemplated under the porticoes, and which Shakespeare developed with such genius, were precisely what Mallarmé sought to make room for in poetry, transforming them in the process. The curious form of the pantoum might have suggested this idea to him. But the pantoum, as it stands, is nothing more than two separate narratives placed side by side. Mallarmé believed that the poet should place himself at the very centre of the ideas and images he has gathered through reflection: not to explain them one by one, but to reveal them through their interplay, drawing them together tightly. In this way, meaning emerges from their interaction, or from the way they permeate one another.

Let us reread the well-known sonnet:

Le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd’hui

Va-t-il nous déchirer avec un coup d’aile ivre

Ce lac dur oublié que hante sous le givre

Le transparent glacier des vols qui n’ont pas fui!

Un cygne d’autrefois se souvient que c’est lui

Magnifique mais qui sans espoir se délivre

Pour n’avoir pas chanté la région où vivre

Quand du stérile hiver a resplendi l’ennui.

Tout son col secouera cette blanche agonie

Par l’espace infligée à l’oiseau qui le nie,

Mais non l’horreur du sol où le plumage est pris.

Fantôme qu’à ce lieu son pur éclat assigne,

Il s’immobilise au songe froid de mépris

Que vêt parmi l’exil inutile le Cygne.

In it, I see the image of a swan, trapped in a frozen pond—struggling, yearning to break free, like a bird craving the vastness of open skies, set against the blank wilderness of snow. I also see the Platonic notion of the soul, fallen from the ideal and longing to return to it as if to its native land; and the idea that genius, by nature of its own aristocracy, stands in isolation. It evokes the poet’s plight as well—exiled in this time and place—where once he might have been hailed as a prophet, now simply lingering beyond his moment. And then there’s the stoic resolve: to conquer misfortune with scorn, standing proud through adversity. Lastly, one could draw from it various moral reflections, perhaps this one, which I think was the author’s intended meaning: that a greater spirit, if it succumbs to the pull of everyday life, becomes a victim of its own past indifference; having failed to sing of the realm in which to live, and not having shaken off in time the prejudices that now imprison it—a captive now, despite its disdain.

Standing at the centre of these ideas and images, the poet takes them in all together, perceiving them in their entirety, down to the finest detail. And when he speaks, it’s not to lay them out one by one for us to examine; instead, he brings them to mind as if tracing the outlines of an emotion we had already begun to feel. In much the same way, certain modern melodies draw on multiple tones at once, drifting between them, never fully resolving into any single one. The opening bars of Tristan and Isolde appeared unintelligible to older classical ears for this very reason; yet it’s precisely in this quality that their mysterious, deep beauty lies.

It’s quite natural that this kind of poetry might remain obscure to readers who rush through it, or to others whose well-meaning efforts are tangled by small missteps. In the sonnet at hand, one image stands at the heart of it all: the captive swan. The idea of a Platonic fall from grace flows directly from it, guiding the poem’s course. And surrounding this idea, related thoughts—harmonic ideas that enrich and expand upon it—have taken shape. Focus might easily drift among these ideas, and that would be unfortunate. For the poem’s essence lies in the simultaneous blossoming of them all. The main image came first, and then, almost at once, the central idea appeared, dressed in the dense, luxuriant foliage of these other ideas, sprouting forth from it like an extraordinary cascade of hair. They are all bound together, not so much by the surface structure of the phrasing, but by their intrinsic qualities; even more so, by the meanings they acquire, either from the poet’s perspective or through their contact with neighbouring ideas.

Thus, the poem doesn’t follow the traditional, rigid logic of the scholastics. What it calls for is something more flexible and refined, with an element of intuition—a kind of logic reminiscent of Beethoven in his late quartets. And with this new logic comes a distinctive syntax, more synthetic in nature, where the harmony of phrases flows in step with the ideas themselves rather than strictly following the order of words.

It’s a new approach, to be sure; and understandably, it was bound to bewilder. Yet all it involves is an unusual application of forms we already know. The surprise lay rather in how an entire system of thought emerged through them. But let’s not suggest that this is anything less than proper French. Grammarians were familiar with all of these constructions that threw so many into disarray; they even named them: ellipsis, synchysis, apposition, syllepsis, and anacoluthon. And surely, they wouldn’t have coined these terms if they hadn’t seen the need for them8.

I have just spoken of harmonic ideas. They surround and penetrate the main idea, much as the harmonic overtones of an instrument encircle the fundamental tone. I’d like to dwell on this analogy a little longer, for it serves well to explain both the obscurity of certain poems and the clarity they reveal once we have truly grasped them.

The simplest example would be that of a bell. The harmonic sounds create distinct notes, and the most beautiful bell is the one that resonates with the richest harmonics. But if I bring it close to someone with only a moderately sensitive ear, they won’t hear the fundamental tone… At first, this tone is obscured by the harmonics, and it is one of these overtones that they will mistake for the fundamental sound. However, if I point out the fundamental tone to them, they will recognize it within the bell and be struck by how it dominates, drowns out, and almost ‘invades’ the others. And as we step back, the fundamental voice soon overtakes all the others around it: from that point on, it will stand alone, and we will listen to its deep, irresistible resonance.

I want to show that the same holds true for Mallarmé’s work. At first, the surprise prevents any deeper thought; the harmonic ideas form an accompaniment to the fundamental idea, which seems almost swallowed by them. The bell is too powerful, and we are too close. The carillonneur, in his tower, hears nothing but a tremendous, indistinct noise. Let us step back. Let us examine the poem: little by little, our minds distance themselves through reflection, and gradually the fundamental tone begins to pierce through the overlaid tones. — The book is closed, I reflect on my reading; the incidental details now take their proper place, the secondary ideas, to which my clumsy attention had once given too much weight, now gently fall into the shadows; and now the poem reveals itself as a whole: and the fundamental idea, isolated by distance, finally reaches me, solemn and bare, like the source sound of the bell.

Now I can open the book again to the same page, moving closer. The incidental ideas will no longer mask the essential one, but will instead form a radiant webwork around it, clear to my now-enlightened eyes. I can approach the tower; the bell continues to toll. The singular voice I once heard from a distance seems to multiply, as harmonic notes, gradually becoming distinct, increasingly enrich the deep, primal sound; they swirl like singing souls circling a mother soul. But it is through them that I will still hear the underlying sound, ever-present.

V

These are the thoughts I wished to share about the work of Stéphane Mallarmé—an unfinished work, as we know, for Death arrived, with its stupid breath, to scatter the pages that had yet to be bound into the Book. Apart from the volume of prose in which the core of his aesthetic is expressed, the master had published only a handful of poems—one of which was left unfinished—and they stand like statues, bestrewn, marking the place of the grand, absent edifice. The hermetic and fascinating poem published in “Cosmopolis,” Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, doesn’t suffice to give us a clear view of the projected book. It’s not even a definite clue, for it must be seen above all as an early attempt at a method the poet had yet to fully uncover, both in its possibilities and its limitations. This is a conception closer to music than literature; it is the breathtaking unleashing of an orchestra where thoughts and images intertwine like musical themes, crashing together like the cry of instruments. The harmonic ideas spiral out in dizzying circles, swirling around the deep bass of a central idea, surrounding it with a tumult of waves. I confess, this poem held me in its grasp for a long time. Never before had Stéphane Mallarmé been so expansively lyrical, and never had he been so perplexing.

Hundreds of solitary pages still hold, I believe, brief notes and the sketches of verses that will never see the light of day; for they are missing the powerful spirit that was meant to bind their images together, and breathe life into these scattered words, now rendered inert by his death.

This man, whose art was cloaked in mystery, left us with the greatest secret of his thought still kept to himself. Fatalists might see here the bitter mark of fate, which abruptly sealed the Supreme Word on lips that were ready to utter it—the very word that summed up a lifetime.

There seems to be a sort of unyielding logic in the tragic ending of this life and this thought, both of which sought solitude. The noble figure of Stéphane Mallarmé thus acquires a deeper, fuller meaning.

A true witness to the finest qualities of his race, he lived heroically alone, surrounded by those whose virtual beauty he attested to—silent, for he was misunderstood.

Misunderstood, for he sought, to the very end,

To give a purer meaning to the words of the tribe.

But more than that, he dared to follow his dream of Beauty to the very edge of the absolute. This is where heroism truly reveals itself—not in grand gestures, but through an unwavering will and the spirit of sacrifice.

I believe there is not a single writer who, in the midst of their work, does not, in some way, think of the reader who will come. It doesn’t quite turn into worry, and this preoccupation is often unconscious, but it’s there. The thought of those friends I hold dear and to whom I wish to be pleasing follows me, though I don’t even realize it. At this very moment, I catch myself thinking of them, and I can tell that this study would be different if I were directing it toward the readers of Le Petit Journal.

One looks too much around oneself. Instead of writing for Beauty, one ends up writing—no, truly, not for oneself: one writes for others; but not with that magnificent generosity one ought to have, with the fraternal selflessness of someone who gives his soul entirely to the world and humbles himself with gratitude. We work selfishly for others, and far too often what drives us is, if not the craving for publicity—far too revolting for poets—then at least a petty desire for fame and glory, and a somewhat cowardly need to be strengthened by the approval of those we admire. Alas, it’s not the lofty hope of discovering a new reflection of Beauty in the eyes that have looked upon our work!

Stéphane Mallarmé had the strength to set aside all these relative things, choosing instead to immerse himself in a singular concern — so that, at long last, a man would bring his entire dream to life, even if afterward he offered it only to himself. His isolation was the necessary price for this lofty goal; it was the most direct consequence of his vision, and it helped strengthen him as well. Thus, he embodied the heroic stance of a man whose heroism was the sum of his life.

A hero, not just the one who surpasses us; rather, the one whom nothing deters, who moves relentlessly toward his aim — and even more so, the one who represents us in beauty, whose example we are meant to love. Stéphane Mallarmé also embodied this third aspect of heroism: he compelled us to love more than we had once admired. There was nothing in him but nobility and kindness, that great heart open to all human pity. And like his heart, his mind had its own indulgences, though not the kind the heart commanded. At a certain height, intelligence draws close to love. It understands everything and forgives everything on its own.

“It is meet that the bard, when he doth fashion his lays, doth bring them forth in mirth,” says Euripides. Our poet lived in modest comfort, barely above poverty — yet with the dignity of a prince. Perhaps he would have known nothing of life but its pains: the weariness of thankless labour, sleepless nights and their long, tormenting hours, and the despair of the impossible work — had it not been for two extraordinary women, Madame and Mademoiselle Mallarmé, who stood as guardians of a small but vital joy in his life.

Beneath the calm that veils it, perhaps this is why a hidden sentiment dominates his verses: indignation. It is the feeling of a soul too noble for anger, a rebellion born of righteousness standing firm before injustice. This feeling runs through the work of Stéphane Mallarmé, yet its intensity is restrained; it is sensed rather than seen. Never does it reflect personal grievances.

The memory of these would be, without doubt, justified by the bitterness of a life lived in humble, undeserved obscurity, and by the awareness of a glory that went unrecognized; but the poet’s mind was too lofty to allow them close. He admitted them only after they were transformed, as echoes of humanity’s endless lament toward its destiny. Stéphane Mallarmé, whose spirit had long found rest in eternal things, knew how to regard the fleeting under the light of eternity they contain. From here arises his radiant calm. Without denying the suffering brought by ugliness, he brushes it aside and lets it slip from memory, for his gaze is always set higher.

Such is the hidden power of sacrifice that sustains heroes: the strength that led him to forgo immediate happiness so he might match his effort to the goal he had set for himself. But let us imagine nothing here that resembles stiffness, much less grandeur. This disciple of ancient Virtue taught it without a word, through the sheer fact of his charm and a natural nobility that welcomed both simplicity and familiarity. In slippers, a flannel shirt, a small pipe resting between his fingers, he would open the door to his modest home. The conversation would spring up quickly. Without any posturing, with natural pauses, it would drift of its own accord toward those higher realms that meditation reaches. A light gesture would illustrate or emphasize a thought; one would follow his noble gaze, gentle as that of an elder brother, subtly smiling yet profound, and at times touched by a mysterious solemnity.

We spent there unforgettable hours, quite possibly the finest we will ever know; hours where we were witness to a selfless reverence for ideas—which is the spirit’s own religious joy—surrounded by every grace and refinement of speech. And he who welcomed us there was nothing less than the Poet incarnate—a heart that truly knows how to love, a mind that understands with depth—looking down on nothing, scorning nothing, for in each thing he saw either a hidden lesson or an image of Beauty.

Certainly, one should never encourage anyone to attempt to imitate the poems of Stéphane Mallarmé. It is always folly to imitate any art, whatever its nature, and his methods may even be perilous: for they are linked to a very particular mental habit, and the charm of these verses lies in the ineffable. Yet they bear witness to an artist’s consciousness, the most admirable ever known, and the great lesson of this Book is that of an incorruptible thought which presents us with its unwavering courage. I know of no more moving moral example, nor one more heroic, than that of this powerful and kind man—”of an unyielding sweetness,” as Anatole France put it—whose entire life was nothing but a hymn to his faith.

.

Notes:

1. Without rejecting them absolutely, certainly. But he had modified their aspects; and memory thus no longer aided knowledge directly1..

2. There are also such surprises in the delicate and reserved soul of Racine. One would find some in the noblest scenes of Phèdre; not to mention the beautiful verse translated from Euripides:

Ah! que ne suis-je assise à l’ombre des forêts

[Ah! why am I not seated in the shade of the forests]2.

3. Such, indeed, is the aesthetic of the sonnets, the final work in verse (I exclude the long poem Un coup de dés; there, the harmonic ideas unfold with an uncommonly lavish richness, but it isn’t an interpretation of an image of nature and strikes me not as a symbol but rather as a lyrical essay).

The lines above are not a doctrine I claim as my own; they only strive to shed light on the poet’s intention as I thought I grasped it the day he spoke to me about his work. — When sketching a theory of the symbol, I wrote in Propos de littérature: “Without daring to attribute to Stéphane Mallarmé, who might perhaps reject it, the authorship of the theory above, I at least know all that those who attended his Tuesdays owe to his words.” A well-meaning critic, should he compare these pages to the text of that small book, would soon notice some discrepancies. The main one, I must point out.

The poet is a consciousness that stays vigilant. Even in lyricism, he must remain his own critic. Stéphane Mallarmé understood this better than anyone, and it’s probably for this reason that he demands so much of the will. In his work, thought reigns and directs. It “guides the meaning” of the images: it somewhat imposes an a priori meaning upon them. — Stéphane Mallarmé’s tact was of unparalleled delicacy and subtlety; and here’s a small detail to show his keen awareness and his effort not to mislead nature. He would jot down brief notes on blank cards: images, likenesses — fleeting thoughts they had sparked in him — and by comparing them, he moved forward in his work. In a sense, it was about controlling deduction through example. Certainly, by deducing in this way, the artist can sharpen or fortify his vision; but to me, it seems less authentic, almost a little contrived in its development.

I prefer that the idea, induced by the poet, be only the natural link between a cluster of images that seem to associate themselves almost on their own. In poetry, I would like to rely on the logic of things as much as on the abstract logic of the mind, which tends to be rigid and often forces a tight relationship between overly narrow aspects. Let the mind observe and compare, but sometimes let it forget its preconceptions. Let us listen with naïveté to what things have to tell us and, above all, let us focus on seeing them clearly, so we can present them as truly alive — “to make nature,” as the painters say. The meaning they originally held will not be diminished, but, I believe, it will appear all the more certain. And this applies as much to dreams as it does to raw reality, through the believability of their details3..

4. He could have pointed to a historical example. Bach, too, was reluctant to include in his fugues those markings of movement and intensity that act as punctuation in music. This was the way all composers before him worked4..

5. Conférence sur Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, first page5..

6. Divagations, p. 273. Phrased this way, the proposition seems to embrace both the objectivity of the external world and its evolution. It’s unrealistic to demand a strict, unvarying solution to metaphysical issues from a poet. Rather, his task is to hover thoughtfully among them, within a certain frame, for he is, above all, a soul in search, a soul that reflects. Yet, the logic of this particular soul has an exceptional clarity, and one might wonder if, in some way, words themselves are falling short of capturing it6..

7. Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le Hasard, published by Cosmopolis magazine7..

8. I would have liked to delve more deeply into the syntax of Stéphane Mallarmé: this is a matter of far greater importance than it might initially appear. The structures of language reveal many hidden truths. One could easily demonstrate—though I have only hinted at it—the essential harmony between the poet’s syntax, his logic, and his entire mental framework. But such a task would require a dissertation of considerable length, one that would drift too far from the focus of these notes8..

This is one of 50+ rare French literary texts translated into English for the first time on this site.