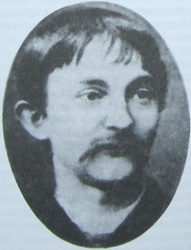

Téodor de Wyzewa (1862-1917)

The three pieces that follow are articles originally published by Téodor de Wyzewa in the press, later gathered together in Nos Maîtres: Études & Portraits Littéraires (Perrin et Cie, Libraires-Éditeurs, Paris, 1895), translated here for the first time.

NOTES ON THE POETIC WORK OF M. MALLARMÉ

by Téodor de Wyzewa

(La Vogue, July 5 and 12, 1886)

"... Astonished not to have felt, yet again, the same kind of impression as my peers." (S. MALLARMÉ, The Interrupted Spectacle)

Ah, Parisians, dear friends, you all know the name of this peculiar poet who, for ten years, twenty perhaps—for what seems like forever—has been publishing, in obscure papers, a handful of verses so baffling they defy comprehension, all under the name (clearly a pseudonym): Stéphane Mallarmé. Some of you have managed to memorize a line or two of his, verses that—no matter how you read them—remain cloaked in mystery. You recite them over dessert, as a party piece, whenever someone calls for a monologue. And you also know he has a rival: Adoré Floupette, as well as a cadre of imitators—young poets equally swept up in Wagnerian fervour and pessimism—our so-called decadent youth. Of course, subtle critics abound, each pressing you toward that same question, the one that sets your speculations alight: is M. Mallarmé a madman, or a master of trickery?

To those—to that one—who, raised in some far-off province, guided by a centaur indifferent to modern ways, might still be oblivious to these things known to all, I’d offer these notes on the work of an artist of the highest order, truly venerable among all.

I

M. Mallarmé began as a Parnassian poet. The Parnassian poets, along with a select few precursors from the sixteenth century and the earlier part of ours, sought to finally give Poetry its place as an art form that arrived rather late to the scene. Verse, at its origin, had served as a mnemonic device, and for centuries it outlived that purpose, remaining bound to it in form if not in function. The Parnassians believed that thoughts labelled “poetic” and vivid images could be better conveyed, more naturally even, through prose; that poetry wasn’t meant to translate, with all kinds of distortions, narratives, landscapes, or teachings but to stir, within the soul, certain musical emotions that music itself could not summon. A centuries-old convention in language has linked specific syllables to particular emotions within our minds. The Parnassians aspired to bring this poetic language to its culmination. They set out to create a symphony of words, unfolding rhythms and sounds in varied forms.

Still, whether out of respect for convention or an incomplete sense of their own aims, they held on to the use of subjects directly conveyed in their verses. Yet, to make their musical task easier, they deliberately chose subjects that were either banal or void: old proverbs, worn-out images, the whole repertoire of romance and pessimistic declarations. They also adopted an air of impassivity, thinking this indifference toward “things to say” would seem more justified. They locked their poems into fixed forms—sonnets, ballads, rondeaux—wrapped in the rigorous trappings of rich rhymes, a choice meant to show that all subjects were equally indifferent to them, all subjected to the same poses, views, and sizes. They would have happily taken on the most common themes, such as the happiness or sorrow of love, their real passion lying only in the variations, the shifting figures of their musical arrangements. Their subjects, in effect, became nothing more than the necessary pretext, like an opera libretto to a composer.

And it was these Parnassian poets who truly revived our poetry: Théophile Gautier, who called himself a maker of verse, diligently seeking, as any good craftsman, new alliances of sound and rhythm; M. Théodore de Banville, who could subject all topics, indiscriminately, to his brilliant form, especially in terms of rhythm; M. Leconte de Lisle, who paid more heed to his subjects yet stands above all as the creator of precious tonalities, at once slow and grave; and M. Verlaine, who, though he later parted ways with the Parnassian school, stayed always its perfect exemplar—a wondrous craftsman, having cleared his soul of thoughts or images, weaving faint, sorrowful, almost fluid assonances; Count Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, the most remarkable of word-musicians, a true master of verbal harmonies, whose poems possess a mysterious, refined charm—like melodies that are impossibly pure. It was through these poets that art was endowed with a poetic vocabulary, enriched further by many others now fading into obscurity.

Among these poets, M. Mallarmé chose his place early on. To the first Parnasse contemporain, he offered a collection of brief pieces, and to the Nouveau Parnasse, a fragment of an ancient scene, Hérodiade. These poems carry the same intentions as those of the Parnassian masters. They are musical studies, explorations of syllables: the rhythms, not especially original; the themes, conventional—perhaps drawn from Baudelaire’s lexicon. Here we encounter life’s suffering likened to a hospital; the poet to a weary bell-ringer; a dreamer’s sorrows beneath the pouring sun; the doomed triumph of boundless, unreachable ideals; the birth of flowers for the artist; the longing to escape, anywhere beyond the world; a woman in love with her own sensuous body.

And yet, without a doubt, these early verses by M. Mallarmé, written in the Parnassian mode—and perfectly comprehensible to all, in the familiarity of their subjects—will stand among the finest of Parnassian verse. Their melodies possess a passion that recalls the youthful phrases of Beethoven. And, much like the early sonatas of Beethoven when compared to the similar works of Mozart or Haydn, these initial poems by M. Mallarmé already captivate with the intentional unity of their musical tone: a logical and necessary unfolding of a motif, a carefully orchestrated arrangement of syllables within that very motif, all aimed at eliciting a profound emotional response.

For instance, let us consider these few lines:

From Guignon:

Above the nauseating herd of humanity,

The wild manes of beggars in azure

Would leap now and then, lost along the paths.

From L’Apparition:

The moon grew sorrowful: weeping seraphim,

Dreaming, bow in hand, in the calm of flowers,

Vaporous, drew from dying violas

White sobs gliding softly across the azure of corollas.

From Les Fleurs:

And you conjured the sobbing whiteness of lilies,

Which, rolling upon the sea of sighs that it caresses,

Rises dreamily toward the weeping moon

Through the blue incense of pale horizons!

If one were to compare these verses to certain stanzas by Hugo, adorned with similar rhythms, the distinction will immediately surface between the poet and the orator.

However, M. Mallarmé has, as befits an artist who has journeyed further, distanced himself from these early poems penned in what one might term his comprehensible phase. Nevertheless, they remain the perfect expressions of a bygone style; especially valuable because they already reveal the unique qualities that would guide the poet toward a new realm of creativity.

They reveal that M. Mallarmé did not bring to art either an instinctive and precise vision of images or a natural affinity for the music of words. The images are few and oddly vague, leaning more towards symbols: there is no vivid description; the colours evoked seem washed out. One senses that the external world, for this poet, does not possess a fully objective existence. Furthermore, M. Mallarmé does not linger on subtle musical variations; he lacks the innate and constant urge for formal exploration; he is not the native guitarist that the works of M. Verlaine, for instance, reveal. Yet even here, M. Mallarmé presents himself as both a logician and an artist.

His poems stand apart from all others in that they are composed. The Parnassians improvised their music, surrendering to incidental discoveries; he was the first to impose a comprehensive plan on the developments of his melody. A conscious logic has shaped the theme, along with—nothing more than—its necessary expansion. From this arises the exemplary unity of musical tone. M. Mallarmé was initially neither a musician nor a painter; yet, perhaps due to this very natural shortcoming, he managed to select for each subject the images, rhythms, and sounds that he deemed most fitting. The piece from Les Fleurs, isn’t it akin to the adagio of a romantic sonata or one of Bach’s religious preludes, evoking profound emotion through a deliberate arrangement of harmonies?

Logician though he was, M. Mallarmé remained every bit the artist. He wasn’t some mere craftsman of verse, enchanted by elaborate artifices and treating poetry as a trade for work hours. Nor was he a noble of thought, like Balzac or the Comte de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, those aristocrats who all but lose themselves in the enchantments of a higher life they evoke almost unconsciously. Rather, he was a true artist: he knew that art is labour, separate from the everyday, and it was precisely for this reason that he loved it. This artistic intention stands out even in his earliest verses—a clear sincerity, a visible effort to live out the emotions he conveys; an undeniable preference for refined images over those of nature; and an allure toward exquisite perfumes, rare furnishings, tapestries, and fine fabrics. His themes, often reminiscent of Baudelaire, reveal the deliberate choices of an artist. M. Mallarmé saw both the tangible world and, beyond it, the brighter world of art. This dual vision, held in constant tandem, already contains the essence of his future work. From the start, he sought to summon that higher world, to evoke it through an artist’s clear-sighted, logical intent—not as a profession, nor as an instinctive or unthinking inclination. And from that moment on, he devoted his entire life to the work of art.

Shall I note one more quality in these early verses? Perhaps a tendency, for instance, to view everything as a symbol. A hospital? It’s our life. The bell-ringer? It’s the poet calling out to the ideal. The rose? It’s Hérodiade. We are far removed from Hugo’s swift, incidental images—those schoolbook tropes discarded in haste. Here, already, life is seen under a double lens, real and fictional. The artist always sees, with equal assurance, both worlds, and he transposes into art all that is sensed in reality.

II

These virtues, made clearer by what would soon follow, shine forth in M. Mallarmé’s earliest poems. They were, by nature, foreign to and above the typical demands of Parnassian poetry; it was only natural that they would eventually guide him toward a wholly new vision of poetic creation.

In fact, as most of the Parnassians shifted away from the craft of refined musicality toward the more lucrative ventures of novels and prose stories, M. Mallarmé—ever the logician and artist—pursued with unflagging dedication the logical renewal of his art. He had, I believe, taken on a demanding labour; he had made himself the craftsman of a challenging task, but for the sake of securing a solitude that would let him rise above the self-interested gaze of the world—a world he now wished to observe as a distant witness, untouched by its fray. And so, in the stillness of forgotten provinces, after hours given over to daily obligations, he pondered deeply the meaning, both present and future, of poetry itself.

He then understood that Parnassian poetry had been a preparatory stage, a valuable foundation—but one now complete—for reaching true poetic form. The Parnassian poets had pursued music within their verse but hadn’t used that music to convey specific emotions. He believed poetry needed to be an art—a free and deliberate creation of a unique realm of life. To accomplish this, poetry would have to align itself with literature, which captures ideas through precise words. Earlier poets had crafted a pure kind of music, seductive by its sound alone; M. Mallarmé, however, felt poetry needed to carry meaning, to bring into being a whole way of life. But this new goal required new means; thus, M. Mallarmé found himself considering what poetry should convey and by what methods it might do so.

Poetry had to be an art, something that could create a world of feeling. But what sort of world? Only one answer seemed possible: poetry, being an art of rhythms and sounds, had to be a form of music that would evoke emotions. Emotions, however, in our minds are inseparable from their causes—from the ideas that provoke them. Abstract pleasure or pain doesn’t truly exist; rather, it is joyful or sorrowful ideas that move us. A sonata, for example, can stir emotions without needing a text, storyline, or program; but first, the language of instrumental music is more precise than the emotional language of syllables, and even then, that music creates a less complete world than dramatic music, where the composer provides both emotions and an explanation of their causes. And for poetry, this need is even more pressing: the emotions that syllables call forth are so delicate and subtle that they absolutely require the support of precise ideas to make them resonate fully.

Emotions anchored in meaningful subjects—this is the purpose of Poetry. Such is the unwavering, fundamental rule that M. Mallarmé clearly grasped: through this, poetry transforms into art. But what subjects suit poetry? These will differ, depending on the unique inclinations of each poet. The shifting vastness of nature, women, gold—such things may stir some deeply, while leaving others indifferent. Every poet must convey, through the music of words, the ideas and emotions that move him most intensely.

M. Mallarmé was an artist; subjects that require a full belief in the tangible, sensory world held little appeal for him. His mind, purely logical, instinctively leaned towards abstract thinking, which made him especially receptive to theoretical pursuits. He found his deepest, most conscious joys in the search for truth. Thus, in his poems, he set out to recreate the pleasure of speculative inquiry, and to do so fully, he had to evoke its subject. He was driven to express his philosophy—not for the sake of stating it, but because only in this way could he convey the exalted, philosophical joys he sought to capture.

M. Mallarmé’s philosophy was shaped by his natural inclinations. He accepted the reality of the world but viewed it as a reality of fiction. Nature with its glimmering enchantments, the vivid, ever-shifting play of clouds, the bewildered stirrings of human societies—all are dreams of the soul: real, but aren’t all dreams, in their own way, real? Our soul is a workshop of endless fictions, filled with a boundless joy when we recognize them as creations born from ourselves. There is an overwhelming joy in creation, a poet’s delight in being lifted beyond the concerns that cloud vision, a profound pride in becoming an eye that sees freely, perceiving the dreams it casts forth. This is the essence of the poems that M. Mallarmé has shared with us.

One afternoon, a faun in that exquisite light of an ancient Orient glimpsed the light-hearted, amorous, playful nymphs. They fled. And the faun, torn by longing, realizes it was all just a dream—forever lost. But he begins to understand that every vision is a dream spun by his own soul, and he tenderly summons back those gentle, fleeting forms. He recreates their shapes, the warm touch of their lips—he’s on the verge of embracing the fairest one… only for the vision to vanish again. But why grieve? At his leisure, he can call forth the lascivious nymphs whenever he wishes, cherished creatures of his gaze.

A noble poet has passed. Regrets? But what is the death of a man if not the vanishing of one of our dreams? The men we think of as real are nothing but the dim opacity of the shadows they will someday become. When they go, only a shadow dissolves. Yet the poet, beyond that empty bodily existence, lives on for us in a higher, eternal life. The poet is a solemn, stirring music of words; and in his death, our memory of him grows clearer, sharper, reigniting the image we hold.

In the lonely cell of his cloister, a monk toils over a painstaking transcription. His life has been one of ignorance and chastity; here he transcribes an ancient manuscript—perhaps an innocent romance from Alexandria, where two shy, laughing children come together. And now, desire begins to seep into the quiet soul of this good monk. He conjures the lovers before him, willing them to relive their tender, forbidden caresses. Soon, he longs to be the blissful lover himself. Is it memory, or vision? More likely, it’s some distant memory, heightened by his imagination. In his desolate cell, he aches to experience that young, enchanting life of love—and so, he lives it. He strolls beside the innocent girl in a familiar garden, and with the arrival of this unexpected love, everything he knows is transformed. Together, they walk like royalty through an enchanted garden, a place so wondrous it surpasses the world as he knew it. All the flowers bloom larger, the lily stems stretch as if enchanted; and together, radiant and entwined, they move through the melodic landscape of a dream… But then, love fades, and the miracle dissolves. The monk remembers he is nothing more than an ageing, solitary soul; he tries in vain to summon that timid beloved once more. Turn back, old priest, to your parchments; return to your shadowed fate as a wraith—soon enough, the final oblivion will swallow you, there beneath the burial stones!

A swan grieves, bound by its wing to the frozen surface of a lake whose waters are held in eternal ice. Once, it might have sung—might have called forth—a world of its own: a place where it could have lived, sheltered from barren winters and all-consuming ennui. But now, it is enslaved to this frozen realm, its wing pinned to the lake’s surface, eternally. Eternally? Can it not tear itself free on this bright, vital day of reclaimed knowledge? Yet its neck thrashes helplessly in this pallid agony; it denies the space that binds it—space it knows it shaped. Cruel habit anchors it to the ground: it may scorn this image of despair, but from now on, it must endure it.

In strange little prose poems, M. Mallarmé had already suggested this ideal view of life.

It’s a beloved lost one, brought back by desire; it’s a simple fairground scene, transfigured by the poet’s unique vision; it’s a marvellous future event, a momentary evocation, conjured in our age of ugliness, of that ancient, forgotten dream: the beauty of woman.

M. Mallarmé’s philosophy in this period of his life becomes, then, a full acknowledgment of enduring Fiction. A line from his prose poems sums it up: “Reality, an artifice, only serves to anchor the average mind between the mirages of a fact.”

III

Through what form should poetry convey the emotions born of these philosophical dreams? This was no easy task, tied as it was to a broader question: by what form can poetry express the ideas that stir the poet, while also evoking the distinct emotions these ideas carry? Mallarmé confronted this challenge directly, and he resolved it as we might expect from him—with the keen mind of a logician and the sensibility of an artist.

First, he embraced an undeniable proposition: that poetic emotion, like any elevated form of art, should be born in the reader’s soul through a creative act much like the one the poet first achieved. The reader will only know the true joy of art if they completely recreate the work of the artist. Thus, poetry should resist cursory or distracted reading; it must remain beyond the reach of those who lack a deep love of aesthetic pleasures, who are unwilling to devote themselves fully and patiently to it. Poetry must be crafted as a lofty sanctuary, closed to those timid in the face of art and open only to those with true resolve. What value would superficial admiration or vague comprehension hold? Poetry must stand apart, a sacred altar of ultimate joy. Music, after all, cannot be understood without musical training; so why should poetry be served up, perfectly prepared, to satisfy the shallow appetites of passers-by?

M. Mallarmé resigned himself, then, to being opaque to those who, before any initiation, expected time for laughter. At this cost, he achieved his goal: to translate ideas and, at the same time, evoke the emotions bound to those ideas.

At the pivotal points of his poems, he has placed precise words that reveal the idea itself—this is the subject, emerging plainly for anyone willing to read through the piece at least once. (Do those unfamiliar with music mock Beethoven because they must first painstakingly decipher his scores to relive their joy?) The subject appears distinctly beneath the flowing modulations of musical syllables, just as the main theme of a fugue stands out, even amid the constant play of counter-themes. At times, too, the poet, for the sake of the music—after all, its beauty is the main aim—must resort to metaphors and circumlocutions. Yet, eventually, the work is complete; and our persistence in reading it multiple times rewards us with the joy of full artistic creation.

For once the literary words indicating the subject are fully grasped, the surrounding syllables reveal their deeper purpose. They provide the musical accompaniment to the idea—how precise, continuous, and finely attuned to the concept they carry! All the refinements of the Parnassian poets are put to use here, yet now thoughtfully and deliberately, by an artist in complete control, fully aware of their expressive force.

I’m aware the work isn’t flawless; some rhythms fall flat, certain metaphors remain obscure beyond reach, and above all, Mallarmé adhered to the fixed forms of traditional poetry, a constraint that may have stifled the full sweep of his melody.

But what do these flaws matter when one grasps the grandeur of his artistic ambition? To convey the highest emotions with poetry—a poetry that is both rigorous and artfully composed!

And I truly believe that, despite its imperfections, Mallarmé’s poetic work remains today the finest example of what the music of words can achieve. It commands our admiration with a deep, elusive charm, born, I think, from two elements: its musical coherence and a sense of inner necessity.

Mallarmé has always approached his work with rare aesthetic insight and a mastery of tonal harmony. Each of his pieces is written in a consistent tone, perfectly tuned to the emotion the subject demands. In the Afternoon of a Faun, there’s a fluid lightness in the syllables, a warm languor, a beguilingly ancient modulation, with an interplay of drifting melodies and sharper notes, as the faun’s illusion fades and flares back to life. In the Prose pour des Esseintes, we feel the steady beat of short, weighty words, building a crescendo of passion that mounts throughout the poem—only to break abruptly, with a single line:

That such a place did not exist.

And here, the melody shifts to rougher sounds: a harsh disenchantment, the monk’s return to his familiar sorrows.

The most outstanding quality in these poems lies in the intimate, logical interweaving of motifs and their development. On rereading, the verses reveal their complete necessity, each melody beckoning the next as its only possible outcome. A mysterious, delicate thread binds every part together. Few poets give such a powerful sense of artistic inevitability as Mallarmé. He is not some fatigued artisan, content to indulge in decorative flourishes; rather, as he himself put it, he is “a humble servant, bound by an eternal logic.”

Would you like a few examples of this poetic style? Here, then—(why not amuse the onlookers?)—is the sonnet Mallarmé recently dedicated to Richard Wagner. In an earlier, masterful prose study, Mallarmé shared his view of Wagner, showing him as a musician driven by genius to create the complete, living drama that literature itself should have brought forth. Here, composing a poem, Mallarmé no longer seeks to explain his views but instead strives to convey and substantiate the emotion stirred in him by this musician—this musician who, in Mallarmé’s eyes, was now claiming the stage long prepared by poets.

Le silence déjà funèbre d'une moire

Dispose plus qu'un pli seul sur le mobilier

Que doit un cassement du principal pilier

Précipiter avec le manque de mémoire.

Notre si vieil ébat triomphal du grimoire,

Hiéroglyphes dont s'exalte le millier

A propager de l'aile un frisson familier!

Enfouissez-le-moi plutôt dans une armoire.

Du souriant fracas originel haï

Entre elles de clartés maîtresses a jailli

Jusque vers un parvis né pour leur simulacre,

Trompettes tout haut d'or pâmé sur les vélins,

Le dieu Richard Wagner irradiant un sacre

Mal tu par l'encre même en sanglots sibyllins.

Here is the time-worn furniture, painstakingly assembled by poets of bygone generations for the arrival of the next. They had intended to soon transport it to a grander palace, one promised to their care. But a funeral shroud has draped its heavy, dark folds over it; the house is already crumbling, and this ancient furniture is destined to be broken to pieces, with the shroud of forgetfulness already descending to cover it.

The venerable furnishings of ancient tomes and lore, now rendered futile and soon to be shattered—the cherished relics of literature and poetry—oh, how joyfully they once gleamed before our eyes! Now they lie, fated to useless rest in a cupboard forever closed, if the collapsing vaults of the decaying house don’t crush them entirely.

For behold! Rising from this scorned realm comes music itself, bursting forth with a triumphant bloom of brilliance, reaching the steps of this palace—the ideal theatre, once meant for the poet—behold! Don’t you hear the joyful fanfare announcing it? A splendid god, Wagner, has arrived as the sovereign of the stage, once prepared for others; and here, as the relics of poetry fall to ruin, the poet himself stands in awe, dazzled, saluting the usurper of the temple he once dreamed of.

Mallarmé’s unique form shines through in this poem: the subject made clear by emphatic words, the emotion conveyed through the tone of the melody, the swelling crescendo of the tercets, and those lines where meaning is intentionally subdued until they become nothing but pure music:

To spread with wing a familiar shiver,

and:

Trumpets aloud of gold, swooning on vellum.

IV

M. Mallarmé has also bestowed upon our French prose some exquisite pages that exude refinement and elegance. To him, we owe a translation of Poe’s poems, remarkably faithful in its restitution of the emotions that lie beneath the words; a preface to Vathek, light and delicate, reminiscent of a chronicle from a bygone era; and an article on Wagner, where, with the impartiality of an artist, he compares the German master’s musical drama to the dramatic ideal he himself has envisioned. It is here that he offers such a brilliant definition of music: “These natural rarefactions and solemnities that music renders, the farthest vibratory prolongation of our ideas.” But may I take a moment to say a few more words about the complete body of M. Mallarmé’s prose works?

Today, we find ourselves ensnared in a dire writing habit, one instilled in us during our college years, which renders us incapable of artistic expression. We initially conceive our sentences as abstract reasoning: we merely inhabit the ideas; then, confronted with paper, we twist our original vision to fit in words unearthed only later, chaining them to conventional structures, whimsically dubbed grammatical, as if the only grammar were not the natural logic that organizes all the ideas within our souls! M. Mallarmé, through prolonged reflection, arrived at a different understanding of style. He aimed first to experience the entire sentence, meaning the complete idea, along with its details, various perspectives, attitudes, and nuances of sensation. Then he sincerely set down on paper his whole vision of this idea: he restored to us the lived sentence intact, respecting the order of sensations, the occurrences, and the roles that different parts of the idea occupied within his soul. It is an artistic and vibrant prose, opaque to newspaper readers, yet offering the learned an unparalleled pleasure of lofty thought translated objectively.

V

These poems and prose are all that M. Mallarmé has published; thus, it is only from these that I have attempted my analysis. However, he did not stop at the forms he had created. As a logician, he continued his inquiries; and as an artist, he constantly directed them toward the advancement of his art. In this way, he envisioned a new work, still unpublished and, I believe, not yet completed. I would like to briefly highlight its essential traits—at least some traits that directly stem from the virtues I have noted in M. Mallarmé.

“The highest work of nature,” as M. Séailles puts it somewhere, “is religions and metaphysics: its final effort is the endeavour to compose in the human spirit a vast ideal poem… And the spirit is the prophet of nature: within it, she stirs the premonition of her future worlds.” These words encapsulate the philosophical journey of M. Mallarmé.

He sensed that the supreme source of emotions for him was the quest for truth; that the world was a fictional reality, alive in the soul of the poet, contemplated and created by his eyes. He then sought to analyse this vision, and to regard it more joyfully, he created a more subtle world. In doing so, he discovered that the parts of his dream were imperiously interconnected: each one the profound image of the rest. The idea of monadology presented itself to him, adorned with his aesthetic embellishments. Everything is a symbol; every molecule brims with universes; every image is a microcosm of the whole of nature. The dance of clouds conveys to the poet the revolutions of atoms, the conflicts of societies, and the clash of passions. Are not all beings similar creations of our souls, born of the same laws, summoned to life by the same motives?

The drifting clouds, the movements of water, the restless stir of human life—each is a scene, unique yet part of the one eternal Drama. Art, as the ultimate expression of all symbols, should be an ideal drama, one that captures and transcends these natural displays, which have found their fullest understanding within the poet’s soul. A drama, then. But offered to whom? “To all!” Mallarmé replies. The highest joy lies in the understanding of the world, and this joy must be shared with everyone. Thus, the supreme work of art will be a drama, one that each person can recreate—suggested by the Poet, rather than explicitly shaped by his individual hand.

And so Mallarmé has pursued the hidden correlations among things. Perhaps he hasn’t seen, in his curiosity, that the symbols are infinite, that he holds within himself the power to renew them endlessly, and that he may find himself worn out, reaching for the impossible task of capturing them all.

He has also sought a form to match this ideal work. Since the poetic drama seems impossible today—men are entangled in trivial pursuits, distracted from true artistic joy—the Poet must, at the very least, write this drama, make the Book, and place his work there for posterity. But this Book could not be the kind found in book stores—slices of paginated newsprint that break the illusion with their clumsy typography. Mallarmé envisioned a poetic form where precise words shine among purely musical syllables, and he believed this form should be elevated by the very layout of the text. So he dreamt of a new Book, one where subjects would stand out effortlessly against the surrounding music. He has pursued the perfect form for the Book; but, like his search for symbols, I fear this quest for the right typography may go on indefinitely. He will not accept that the exact marks might matter less, that a reader’s goodwill could compensate for any flaws in the material. From here on, his soul will chase the ever-moving, elusive dream of ideal perfection, and his life’s work may remain forever unfinished—unless he tears himself away from these captivating illusions to reveal, with whatever means he has, some radiant parts of the universal symbol.

I express here a concern, not a critique. Only those who finally witness the fulfilment of this work—into which Mallarmé has poured his life, the work promised for so many years—only they will be fully entitled to appreciate his new ideas. And so we must await it, with a sort of reverent despair.

M. Mallarmé’s place in the art of our era remains no less remarkable, both beautiful and noble. This cherished poet will have earned the honour of seeking to raise the purpose of poetry itself, devoting it to the expression of true, defined emotions. Already, despite the mockery, he has inspired others to follow in this valuable path. But whether or not he has successors, whether he completes his admirable endeavour or leaves it unfinished, he will command our admiration above all for simply being an artist.

For it is he alone among us—or at least to a degree higher than any other—who has shown us the image of a true artist. Mallarmé alone has always chosen, over all wealth, over all fame, the free and deliberate creation of an artistic life. A madman, one might say? Yes, certainly so, if madness is indeed nothing but a “difference.” And not the madness of some other extraordinary visionary, who also brings a different world to life, but does so instinctively, without the conscious joy of recognizing himself as creator. The artist’s madness is something higher; it’s a madness that brings joy. It gives him the freedom to see everyday reality and, by choice, build something better above it. It grants him the ultimate pleasure, the joy of knowing himself, of daring to make himself different!

Surely, M. Mallarmé knows this joy. Beyond our trivial distractions, calm and smiling, he observes the birth of his ideal visions. He has built his art’s temple so far from the world that he has placed it beyond even Glory itself. He will never know what so many other poets today do: the tarnishing of his works by the debasing admiration of fools. And he will savour the joy, sacred and exquisite, of forever witnessing, in the serene clarity of his noble spirit, the mockery and scorn of those who fail to grasp the beauty of his unfathomable madness.

THE SYMBOLISM OF M. MALLARMÉ

by Téodor de Wyzewa

(Revue Indépendante, February 1881)

For all these years I’ve heard talk of it, I must confess, I still don’t grasp exactly what a symbol is—or rather, the more I think about it, the less I’m sure, overwhelmed by the sheer range of meanings that people heap onto this word. A symbol, I believe, is first and foremost a sign—an object meant to stand for another object. If that’s so, then one might be a symbolist simply by using signs to convey one’s thoughts: words, tones, colors, and lines, each giving form to the artist’s mind. But in this sense, all art would inherently be symbolic. A symbol can also be more than a mere term pointing to an idea; it can be a straightforward concept meant to represent a more complex thought, something harder to grasp. In this form, a symbol becomes like the scholastic trope or analogy, a concrete rendering of a general notion—a story invented to embody or bring a theory into clearer view. This kind of symbolism often proves essential in art, especially in emerging art forms aimed at broad, straightforward audiences. Still, I believe that higher art should aim to avoid it: a thought expressed in its precise, unvarnished form—even if abstract—may indeed be harder for all to understand, yet those who grasp it do so more profoundly, sharing the artist’s vision more intimately. At the very least, it’s certain that our young poets’ symbolist school doesn’t use “symbol” in this way; they bypass philosophical themes and abstract doctrines, clearly not concerned with making their thoughts more accessible to the general public. I’ve come to think that, for these poets, symbolism is simply the act of replacing one idea with another. So, if I wanted to evoke the scent of a flower but found no word that captured it directly, I might resort to describing it symbolically as a soft grey.

The exercise may refresh a few select souls, but I confess, I struggle to see much artistic value in it. Rather than fixating on this back-and-forth exchange of sensations, wouldn’t it be far better to expand our vocabulary—letting each term keep its own distinct meaning and reaching instead for that ideal of a thought expressed with true accuracy? I even believe the genuine revival of our literature (not merely our poetry—after all, what place do these issues of grammar and symbol hold within poetry?) would lie in precisely the opposite approach to what the symbolists envision. Rather than twisting words away from their natural meanings, we should restore some of that essence lost over the past century. Don’t our young writers see that nearly every word in the Dictionnaire de l’Académie has become almost unusable? Each one can now mean forty different things through metaphor alone, and at this rate, soon enough, any one of them might be replaced, with no change in meaning, by hundreds of others.

I have no problem venerating the symbol in art; I simply ask to see it put to a genuine artistic purpose. I know that M. Stéphane Mallarmé is striving, with admirable constancy, toward creating an art that is purely symbolic. Yet surely, the unique charm of his work owes itself not to his use of symbols, but to the life he breathes into it—the noble height of his ideas and the expressive harmony of his syllables. These, at least, are the qualities that captivate me in all of M. Mallarmé’s poems, far more than any symbolic weight they might hold. Here we find delicate paintings that stir and animate the artist’s soul, conjuring a world of fierce or desolate passions—the unifying theme that rises above the varied shapes and shades.

For example, here is a series of three sonnets recently published in the Revue Indépendante:

Tout Orgueil fume-t-il du soir,

Torche dans un branle etouffee

Sans que l'immortelle bouffee

Ne puisse a l'abandon surseoir!

La chambre ancienne de l'hoir

De maint riche mais chu trophee

Ne serait pas meme chauffee

S'il survenait par le couloir.

Affres du passe necessaires

Agrippant comme avec des serres

Le sepulcre de desaveu,

Sous un marbre lourd qu'elle isole

Ne s'allume pas d'autre feu

Que la fulgurante console.

First, a console stands beneath the cold marble of the fireplace. The poet, thinking back to the joyful flames that flickered there just moments ago and are now gone, wonders if all pride, and the youthful blaze of splendours, dreams, and glories, will meet the same fate when evening falls—if every last glimmer will be extinguished, leaving behind nothing more than the fleeting trace of smoke in the place where that torch once burned so brightly, now choked by some fatal stroke. Is evening really going to reduce all pride to smoke, just like that fire in the marble hearth? Will the triumphant burst of its flame never manage to hold on, to resist that surrender? But the blaze dies out, inexorably; and should the heir to some extinguished trophy, its own splendour snuffed out by fate, return to this empty house, he would find the room cold—cold, alas! because the deadly evening has arrived. In vain, he tries to escape through dreams, to forget this ominous sight; but memories of the past cling to him like the talons of a powerful bird, holding him fast. Condemned to endure the chill of this room once filled with light, he suffers. Yet soon his suffering eases, for he has seen—not the darkened hearth, but something rising in the night beyond, and from the depths of his heart—brilliant, oh! so brilliant that it gives him the illusion of that lost flame and its warmth. He sees the spark of that console and finds the true hearth again, the blaze of the all-powerful dream that will never die.

Surgi de la croupe et du bond

D'une verrerie ephemere

Sans fleurir la veillee am ere

Le col ignore s'interrompt.

Je crois bien que deux bouches n'ont

Bu, ni son amant ni ma mere,

Jamais a la meme Chimere,

Moi, sylphe de ce froid plafond!

Le pur vase d'aucun breuvage

Que l'inexhaustible veuvage

Agonise mais ne consent,

Naïf baiser des plus funebres!

A rien expirer annonçant

Une rose dans les tenebres.

Now, on the table, there’s a vase—a slender vase that once held radiant flowers. The poet notices it, contemplating its delicate, curving form, the fragile sweep of glass poised as if to leap, then the neck, rising only to break off abruptly. He sadly reflects that no flowers remain to console his bitter vigil. Here, he finds his poetic spark, and then emotion stirs. Why, he wonders, can he not summon the flower he longs for within himself? Can he not conjure it by his sheer will? Ah! It must be that, by birth, he’s condemned to fall short; some inherited inertia holds him back. Perhaps his parents failed to endow him with that power of evocation, failed to draw from the bountiful spring of Chimera—and so the source, left untapped, has dried up. Alas! the vase stands without its warm crown; it languishes, useless, bereft of any refreshment but its own hollow emptiness, refusing—oh! the punishment of inheritance!—to finally bring forth, from the artist’s sterile wish, the blooming crown that would consecrate him: a fragrant blossoming of roses.

Une dentelle s'abolit

Dans le doute du Jeu suprême

A n'entr'ouvrir comme un blasphème

Qu'absence eternelle de lit.

Cet unanime blanc conflit

D'une guirlande avec la même,

Enfui contre la vitre blême

Plotte plus qu'il n'ensevelit.

Mais, chez qui du rêve se dore

Tristement dort une mandore

Au creux neant musicien

Telle que vers quelque fenêtre

Selon nul ventre que Ie sien,

Filial on aurait pu naître.

A lace curtain: here lies the third subject. Through it, the poet feels the suggestion of a bridal bed. Yet, looking closely, he finds no bed beneath the lace; it appears almost sacrilegious, parted as it is over the bare emptiness of the pale window. This white, monotonous clash, endlessly retracing its faint lines across the glass as if seeking escape—it drifts but fails to veil the bridal bed that would have suited it. But now the Dream arrives, sweeping away the bleak thoughts, for within the soul touched by the dream lies an eternal, harmonious mandora—this magical lute of fantasy that rests deep in the soul’s depths, where all music is born. And what does it matter now if no bed is beneath that lace? The poet envisions himself willingly as the child of the Dream, son of that eternal force rooted deep within his soul. Isn’t the rounded body of the mandora itself a royal womb, nurturing, above all the illusions of fleeting life, the innermost life of imagination? And that lace that only moments ago was fading—see how now it becomes a sumptuous backdrop for the truly real bed, where the poet imagines his own birth!

In these three sonnets, Mallarmé has aimed to glorify—through a variety of symbols—the indestructible Dream, ruler of all things. Yet, isn’t the symbol here simply a pretext, while the true subject is something else entirely: allowing poetic emotion to rise within him, sparked by everyday objects, held up always by that noble faith in the Dream as a comforting guide? Perhaps he sought to express visions through emotions, to show the intimate connection between the two. But for me, it is in the emotions he conveys, and in the remarkable music with which he clothes them—not in any symbolic intent—that the true beauty of these poems resides.

THE GARLAND OF M. MALLARMÉ

by Téodor de Wyzewa

(Figaro, December 8, 1893)

M. Mallarmé’s renown is universal. In England, Italy, Poland, and the United States, eminent critics have gone to great lengths to celebrate him. Like Victor Hugo in his day, he is the one whom young travellers from abroad eagerly seek out as soon as they arrive in Paris. Recently, when provincial newspaper editors were asked about their literary tastes, they included him among the few writers they would like to see in an ideal Academy. And if he’s not already the most recognized of our poets, I have little doubt he soon will be.

Many, it’s true, know of him without having read his verses—but then, these days, no one reads poetry at all. Indeed, many are happy to imagine him as some extraordinary figure, set apart from the everyday world; but isn’t that just the way we ought to imagine a poet?

As for M. Mallarmé himself, he greets fame with the same serene, proud smile that he once turned upon mockery. Few artists, perhaps, have had to endure as much casual, small-minded derision as he has. Yet M. Mallarmé is wise. Neither ridicule nor fame reaches him in the diamond tower where he keeps to himself; and the tangible world has never seemed real enough to trouble him in his contemplation of a higher reality he knows he holds within.

He sought only to offer his admirers the chance to read him. At last, he’s resolved to release a popular edition of his poems, in both verse and prose, which until now have remained scattered across distant journals or bound in costly, limited-edition collections. This new edition is, to be fair, just a selection—or, to use M. Mallarmé’s own delightful term, a “florilegium.” Yet the flowers gathered here more than suffice to form a rare and precious bouquet, one whose fragrance I could breathe in endlessly. Among them, I discovered several poems from M. Mallarmé’s early period, which, while delightfully clear and in a purely classical style, still strike me as the noblest, most passionate, and harmonious poems written since Lamartine.

There I discovered, too, several poems from Mallarmé’s later period—the very pieces that once drew so much criticism and mockery, and which now underpin his fame. I had the privilege of being among the most passionate admirers of these works during a time when the consensus still largely deemed them ridiculous. With what emotion I revisited them! How many memories they stirred, how many old dreams came rushing back! It proved quite challenging to examine my thoughts on them openly, to untangle my current impressions from those cherished feelings of the past!

***

It is Fontenelle, I believe, who once remarked, “I was very young when I learned philosophy, but already I began to understand very little of it.” My situation regarding the poems of Mallarmé’s later period is quite different. I was still quite young when I first encountered them, yet I understood them immediately; there isn’t a single one so obscure that I couldn’t break it down word for word. Through the thickets of their tropes, I moved with as much ease as Hellenists must navigate the darkness of Pindar.

One day, while I found myself marooned and resource-less in a small town in Germany, I considered taking up a profession that would allow me to make a living. It struck me that the most practical solution would be to open an office devoted to the complete and guaranteed interpretation of Mallarmé’s works. And perhaps, as my clientele grew, I might have even struck it rich in this line of work: for I truly grasped the meaning at a glance and could translate the most challenging passages with ease. I could untangle the meaning behind every inversion, every parenthesis, and even the word ptyx—

An abandoned trinket of resonant nothingness

that is to say, a word that is purely euphonious and utterly devoid of any meaning.

Alas! It remains a profession that, today, would be beyond my capabilities! For I must admit that I no longer grasp these exquisite poems of Mallarmé with the same literal precision. It’s not that I have forgotten my earlier interpretations; rather, I find myself uncertain of their accuracy, and next to them, I stumble upon other interpretations that seem equally legitimate. I see obstacles rising once again that I thought I had pushed aside. I fully comprehend the overall meaning of the poems, and enchanting details catch my eye at every turn; yet now, there are aspects I wouldn’t dare to explain.

Thus, the poetry of Mallarmé seems to me less clearly explicable than it did in the past; yet never, in contrast, has it struck me as so beautiful, nor has it ever touched me so profoundly.

I struggle to reconcile myself with the obscurity of a moralist; among Ibsen’s works, for instance, I can only genuinely admire those pieces that I fully grasp. Yet, the same does not apply to poetry. As I become more attuned to the obscurities within Mallarmé’s verses, I also begin to discern and appreciate the reasons behind the complexities that sometimes shroud these poems. If Mallarmé has moved away from clarity, after having been so in the splendid poems of his earlier style, it is because he aspired to elevate poetry to loftier heights. He envisioned a form of poetry in which the most diverse orders of emotions and ideas would be seamlessly intertwined. With nearly every line, he sought to weave in multiple layers of meaning. Each verse, in his intention, was meant to function as a vivid image, an expression of thought, a declaration of feeling, and a philosophical symbol; it was also designed to be a melody, as well as a fragment of the poem’s overall musicality—all while adhering to the strictest rules of prosody, so as to forge a perfect unity, akin to the artistic transfiguration of a complete state of soul.

This represents the most noble attempt ever made to elevate poetry, to firmly establish for it a higher purpose that transcends the shortcomings, the approximations, and the clichés of prose. While many nuances may inevitably slip through our fingers amid such a variety of subtleties, we can still grasp the grandeur of the entire work. A delicate charm washes over us, a subtle fragrance lingers in the air, accompanied by a gentle flow of sweet and pure sounds.

Such is, at least, the impression that these poems leave on me: The Afternoon of a Faun, Prose for Des Esseintes, and the sonnet of the Swan. I am convinced that this is an impression they will evoke in any soul with a bit of a passion for beauty, on the day when one decides not to place such exclusive emphasis on the intellectual aspect of poetry.

Ah! That damned need to understand that we carry with us in everything today, which ravages our lives, corrupting our only true pleasures at their very source! I feel ashamed for having succumbed to it for so long: it now seems to me that in my attempt to explain, to translate the poems of M. Mallarmé into abstract ideas, I was reducing them to mere elaborate puzzles. Their worth is, in fact, so much higher. They are not just works of literature, but rather of art. They reach out to our sensibility, transcending our intellect; we must embrace them as they come and let ourselves be enchanted. For their poetry is, above all, a melody.

***

And the poems of M. Mallarmé do not solely exhibit the music that arises from variations in rhythm and the arrangement of words. They also resonate as a harmonious echo of a poet’s magnificent soul; it is through this quality that they touch me most profoundly and have exerted such influence over young generations for the past decade. For all of us fortunate enough to have encountered him, M. Mallarmé will forever remain the perfect embodiment of the ideal Poet.

Man is indeed as Mr Whistler portrayed him on the frontispiece of the new edition of his works—head held high, eyes raised, serene and disdainful; yet how many other qualities do we know of him that Mr Whistler could not quite capture! M. Mallarmé stands as a poet, the last of the poets. It’s impossible to imagine a peculiarity more natural, more free from artifice and pretension. His thoughts spring forth spontaneously, fully adorned, elegant, subtle, and unique, just as one would expect from a poet. His conversation is a carousel of colorful visions—discreet and charming, effortlessly traversing a range of subjects, never losing its artistic touch or poetic grace.

And beneath it all, there lies an unfailing benevolence, the gentle indulgence of a sage, along with the most remarkable examples of dignity, nobility of soul, and selflessness.

This is what M. Mallarmé teaches the young poets who flock around him. Yet it would be a mistake to think of him as their master in poetry; he has no disciples and desires none. The conception he holds of poetry is far too elevated; it demands an effort that others might hesitate to devote their lives to, especially in a time when poetry is scarcely a priority, and prolonged pursuits fail to entice anyone. M. Mallarmé is not the initiator of a new poetry; rather, he stands as the final representative of the old. He has merely pushed to their utmost limits the principles embraced by all the great French poets since the Renaissance. His art presents us with the strange and delightful charm of those sunsets that paint the horizon in a thousand delicate shades after the warm glow of an autumn day.

This is one of 50+ rare French literary texts translated into English for the first time on this site.