The Marquis de Cluses was slowly recovering. Though still too weak to rise, lingering in a fragile state with an uneasy mind, the shadow of danger had begun to lift. One morning, he wept profusely in the arms of the Countess and the Colonel—tears that gave way to a heavy, restorative sleep. Not a word about Thérèse escaped his lips. No utterance seemed worthy of her, and neither base vanity nor any desire for display moved him to parade his grief before the world.

They thought it wise to bring him the child—but he turned away. His heart remained entirely hers, his reason too delicate, too embittered to forgive the infant whose birth had cost Thérèse her life.

Only M. de Caristy could distract Agénor from the spectral terrors and relentless self-reproach that gnawed at him. He did so with countless anecdotes, lulling him with tales of the revolution, the Army of Condé(101), the Duke d’Enghien, the royal family—stories of faith and hardship, of outposts and guardrooms. Throughout these recitations, the Chevalier’s cornelian(102) snuffbox never left his robust hands, passing from right to left and back again.

As soon as the young widower could stand, when his lungs had regained some elasticity, his first concern was to visit Thérèse’s tomb in the chapel that served as the final resting place for Robert de Cluses and Jenny Gainsborough. There he wept without restraint, refusing to accept his grief, beseeching God to take him, imploring the Virgin to intervene—whatever the cost to his immortal soul. Yet far from breaking him, these tears brought relief, and his desperate prayers, passionate as they were, provided a bracing change of focus.

When he had regained most of his former vitality, a quiet restlessness compelled him to emerge from seclusion. In the deepening twilight, with its enforced silence and the memories it thrust upon corroded souls, Agénor took on the aspect of a man prematurely aged, weighted with remorse. Apart from this, a redoubling of devotional practices, and the obscure disdain he showed towards the child he had created, his manner betrayed nothing extraordinary.

Seeing this, the Count and Countess de Montégrier, preparing to return home, offered to take charge of their granddaughter. Agénor flatly refused. That same day, encountering the baby in her nurse’s arms near the budding edge of the park, he spent ten minutes listening to trivial chatter, testing himself—was he truly capable of hating this slight creature of flesh and bone, rosy in her swaddling clothes, or was he deceiving himself with a twisted sentimentality that merely mimicked genuine feeling?

His introspection yielded only half-answers. Settled in the Picardy nursemaid’s lap, the infant gazed with vague blue eyes, her dimpled hands moving, her tiny skull beneath a frilled bonnet working her lips as though suckling. The Marquis de Cluses smiled. How could he harden himself against such an adversary? Whom did the child resemble? Colonel de Montégrier? Thérèse?—whose every feature, gesture, and expression crystallised vividly in his sorrowful memory. No… but undoubtedly some ancestor, a face from the ghostly retinue that trails behind every family name.

Agénor pushed deeper into the sheltered park. Still madly in love with his wife, her dear voice anchored within him like a ship in harbour, he walked with moist eyes, believing she would have helped him learn to love their child. Perhaps—who knew?—the way mothers naturally cherish their infants kindles the father’s affection for their common offspring.

The time came for the Montégriers to depart. Thus deprived of guests, the château regained its former torpor, its enormous and almost mute appearance, though it was far from empty.

The Marquis’s sadness increased. Sharpened by solitude, vigils, and fasting, nourished by the very excess of a misfortune in which he took a certain pleasure, it became consuming, morbid. Agénor grew thin again, becoming once more a shadow of himself, whilst developing an uncanny ability to fix upon a single, unwavering obsession.

He had forbidden anyone to enter the room where Thérèse had died. He himself went there frequently, obeying an unmistakable inner summons. With shutters closed and a single candle lit, he would sit in a corner, the better to embrace it all. Surrendering to the evil that obsessed him, to perfidious contemplation, he would sob, pray, call for Thérèse, implore heaven for a miracle. As the hours drifted by, the straw and gold hangings seemed to come alive in the church-like glow. This animation spread to the curtains, the canopies, the bed, each piece of furniture as his gaze fell upon them. The wretched man felt his flesh quiver, his thoughts evaporate under the strain of such consuming attention.

These sensations were, initially, the extent of his experiences—except during certain silences, when he felt extraordinary shivers, like invisible fingertips upon him, and vertiginous moments of clarity that evoked unsuspected figures and visions unrelated to his conscious concerns.

One afternoon, something—a murmur, then a sigh—exhaled to his right. He turned but found himself alone. Thérèse’s room remained closed as usual, but on the mantelpiece above the candle, a long flame panted and swayed. Then—whether within him or outside, none could say—a thought formed with startling clarity: Napoleon is no more, since the fifth of May.

The candle flame steadied. A peaceful interlude followed, the park birds singing their hearts out. His rationality reasserting itself, Agénor marvelled at how completely this peculiar trick of mind had taken him in.

Two weeks later, a letter from M. de Montégrier announced the death of the former Emperor, the modern Cartouche(103). The news was only just emerging.

Terrible apprehensions assailed the Marquis when he reflected on his uncanny premonition. For several days, despite his usual courage, he dared not enter the sanctuary where other surprises might await.

In vain he told himself: “Mere tinnitus… The candle was guttering… Random chance creates the most peculiar connections… If God had answered my prayers, Thérèse would have appeared to me, not Bonaparte!” Repeatedly he would fall still, troubled, seized by dreams that seemed whispered to him.

He wandered through realms of light and blue darkness where billions of pale shadows ebbed and flowed like spectral tides, draped in white, wings rustling, magical orchestras pouring forth ecstasy. The stars trembled like distant hearts, nearer than ever across unimaginable spaces. At other times, his mind filled with visions of the grand century(104): midnight feasts, Versailles cavalcades, games, celebrations, battles—populated by figures trembling with life, exchanging words, displaying their vanities and joys, their customs and troubles perfectly preserved, as if divinely reincarnated.

Twenty times, when the burden became unbearable, he nearly confessed everything to the curate of Juvigny, his spiritual director. But whenever he prepared to unburden himself, the words died in his throat. A will not his own struck him mute.

Little Berthe was growing visibly. Agénor allowed the child near him twice daily. He no longer suffered utter despondency, so completely did his spiritual fever carry him beyond earthly concerns.

He returned to entering Thérèse’s bedroom, driven by unknown force, nerves frayed despite his determination. There he breathed an atmosphere of acrid delights and subtle bitterness.

A month passed—uneventful, making no impression. The Marquis had banished his anguish when, one day, servants saw him tumble down the castle steps.

“Monsieur de Caristy?”

Having gone riding after lunch, he had not yet returned.

With haunted eyes, gaze elsewhere, voice faltering and hands trembling, Agénor accosted one servant after another—gardeners, his valet, the coachman—making painful attempts at trivial conversation. Then, simultaneously ashamed and annoyed at dawdling amongst the servants whilst gentle rain cut through heavy air, he spent two hours muttering prayers and pacing from entrance hall to garden boundary, as if more at ease there under the vast sky.

When Monsieur de Caristy finally appeared on his stocky cob near the main gate, Agénor ran to him.

“I must speak with you… immediately…”

The steward’s boots bore muddy splashes, water dripping from his hat, though Agénor noticed none of it.

“Here’s the matter!” he declared once they were in the library, but his throat constricted.

The chevalier savoured a delicious pinch of snuff.

Agénor gathered himself: “I’d be grateful if you kept this to yourself… It’s important you understand I’m not mad.”

Stupefied, Monsieur de Caristy nodded. With profound distraction, he balanced his cornelian snuffbox atop three fingers, contemplating its semi-transparency, the sinuous frozen streams, red upon red.

“This is what I must tell you,” said Agénor. “Thérèse… the Marquise has appeared to me.”

The snuffbox nearly hit the floor; the chevalier caught it mid-flight.

“The Marquise de Cluses?”

“Yes. I was thinking of her… A murmur enveloped me: ‘Don’t be afraid…’ And I saw her, clear as I see you now.”

Speechless, Monsieur de Caristy clutched his snuffbox, weighing it mindlessly.

“Devil!” he said. “Devil! Devil!”

He glanced briefly at his companion.

“You’re certain? Not mistaken?”

Agénor interrupted: “I should tell you I’ve been begging God to return her to me… I’ve suffered greatly… wept bitterly… We loved each other…”

Tears rushed to the young Marquis’s eyes. The snuffbox gave a little start, then began to pitch between its owner’s thumb and forefinger, expressing better than words the emotional communion between the two men.

The sky had darkened further. In the library shelves, the morocco-bound books with their gilt seemed like attentive listeners, they too full of the inconceivable.

Aware of the chevalier’s understandable scepticism, Agénor insisted:

“I saw her… saw her! Just as I see you.”

Monsieur de Caristy muttered again: “Devil! Devil!”

The snuffbox disappeared into his closed fist.

“Where were you when…?”

“In her room.”

A corner of the snuffbox peeked out, winking with reflected light.

“The shutters no longer closed, then?”

“I always light a candle.”

The cornelian snuffbox retreated to its hiding spot.

“This… vision, did she speak? Explain her presence?”

“No, I ran away… I was afraid.”

Lost in thought, the chevalier reflected: Poor Marquis! Grief has overturned his mind… Such a modest fellow… upright and good… possessing such fortune… Ah, Caristy, you imagined you’d earned respite from hardship? That you’d no longer be penniless? No, my friend, think again… In the next world you’ll be rewarded for blood spilled for God and King, for kith and kin cut short by Madame Guillotine…

He inhaled a pinch of snuff, laying the box on his thigh. All this pained him enormously.

“Will you write to the Colonel? Or Madame la Comtesse?”

“They wouldn’t believe me.”

That’s not a madman’s remark, thought Monsieur de Caristy. He pocketed his snuffbox, only to retrieve it immediately.

The tear stains had dried on Agénor’s mournful face when he murmured:

“I was wrong to run… The more I reflect, the more I blame myself.”

“One cannot reason with panic.”

“Truly, there was nothing to fear.”

“Eh! Eh!”

“No, truly… A shadow rose in the room upon my arrival. At first I paid it slight attention, completely unsuspecting… But the shadow gradually took colour, assumed form, became wreathed in light. And I recognised Thérèse, in one of her favourite costumes, glossy linen… That’s when I heard: ‘Don’t be afraid…’ She was smiling, approaching… You know the rest.”

A shiver ran through Monsieur de Caristy.

“Listen! She must be here,” said Agénor. “She is here, I feel it!”

Though increasingly dubious, the chevalier gripped his snuffbox, prepared for whatever might come.

Outside, rainwater gurgled through gutters. Within the library, profound silence had fallen—abruptly shattered by three knocks. Three sonorous, otherworldly knocks struck the tall mirror above the fireplace. These sounds, at once familiar yet utterly alien, announced to their trembling nerves that something beyond nature had entered their presence.

“There! What did I tell you?” stammered the Marquis, ashen-cheeked, pupils darkened.

The steward bellowed, terrified: “Yes… I cannot explain… It’s marvellous! And upon my word, if it happens again…”

No response came. But the moment Agénor mentally voiced the same desire for proof, the unseen intelligence responded promptly with another series of three knocks.

Instantly, uncanny resonance filled the library, vibrating through furniture, floor, and walls. Abruptly, a heavy oak armchair came alive, gliding towards the Marquis. He was seated in it. The chair creaked towards a table where writing materials always waited—pens, paper, pencils. His muscles powerless whilst his soul rebelled, crying No! No!… I don’t want to… You’re killing me!—he wrote by force.

Terrorised, Monsieur de Caristy neither moved nor spoke. The air pressed down, making movement a struggle. The entire castle came alive with sound—cascading knocks racing through ancient stonework and aged timber, ghostly twins to those first haunting taps.

Finally, the unearthly clamour quieted. For sixty seconds, Agénor appeared lost to this world. When his eyes reopened, he was stunned by profound exhaustion, with no memory of what had transpired. His bewildered eyes sought the chevalier.

“I believe you’ve written something… Read… before you.”

A dark raindrop suspended from his nostril, the snuffbox retaining warmth his body had lost.

Rain lashed the library windows as dusk approached, casting the gilded volumes into deepening shadow.

Agénor silently passed the paper to Monsieur de Caristy.

“It is indeed I, Thérèse, who am here,” the steward read. “I shall never leave you again… I love you, you alone.”

The Marquis had slipped into a dreamlike state, will no longer his own. Humbled beyond measure, the chevalier felt his utter smallness—a mere atom adrift in creation’s boundless majesty. Distractedly setting his snuffbox on the marble console, he left without another thought.

Days slipped past, remarkably similar despite ever-changing skies and fleeting skirmishes between sunlight and shadow.

The sickly, disquieted Agénor, whose life had been unravelling like scattered clouds, was no more. Eating well, sleeping deeply, he had resumed reading and renewed his passion for hunting antiques from that uniquely admirable era. His complexion and hair reflected blossoming health. Day by day, his old self resurrected.

Solitude remained dear to him, but no more locking himself away. The chamber where Thérèse had died, no longer sealed, ceased to exert special pull—just another room.

Even as daughter Berthe’s smile formed, lips learned to babble, and silken hair grew longer, she remained utterly indifferent to him. Nothing about her touched his heart. Unyielding as marble, he felt nothing. Though she was Thérèse’s flesh living on, she appealed only to his logical mind.

Monsieur de Caristy habitually asked during post-dinner conversations: “Well then, sir, what news since that famous evening?”

But Agénor avoided direct answers, finally imploring the topic be dropped. With no answers forthcoming, the Chevalier witnessed only rare phenomena—mysterious occurrences that shared living spaces sometimes reveal to the properly attuned.

Once, a tall bronze lamp, fully lit, moved purposefully through August night air, drifting from credenza to secretary desk, clicking as it came to rest. Another time, mysterious flowers materialised—natural blooms inlaid with azure, bizarre pistils, astonishing calyxes sprawling magnificent and red across rounded vases, remaining fresh three months. Most unsettling was the incomprehensible duplication of the Marquis, who appeared simultaneously seated against a bust’s pedestal whilst his perfect double examined prints nearby—same face, blue coat, yellow waistcoat, pleated trousers, seemingly fashioned from identical substance.

Whether delusions of mind, deceptions of eye or soul, or jugglery from beyond the grave—these phenomena invariably left Monsieur de Caristy profoundly confused and fearful. By turns convinced or doubtful, he alternated between rebuking his gullibility and congratulating himself on grasping truth, convictions swaying with daylight, coloured by uncertainty. The Infinite kept its silence.

Fifteen years passed. Under Europe’s banner, France marched into Spain. Courier lashed out with his pen. Béranger, that anticlerical Bonapartist, turned politics into ditties. With Louis XVIII gone, the hopelessly outdated Count of Artois took his place, feeding a billion to returning émigrés, re-establishing primogeniture, and, in sheer folly, having himself crowned at Reims like his forefathers. The names Chateaubriand and Royer-Collard were on everyone’s lips. The Greeks threw off the Turkish yoke. No sooner had Algiers fallen than the king attacked his subjects’ liberties. Revolution broke out in July, sweeping aside king’s guards and Swiss allies. Charles X gave way to Louis-Philippe with Laffitte at his side. The final Condé scion, worn down by a harlot, hanged himself ignominiously. The nation endured cabinets led by Perier, de Broglie, Guizot, and Thiers. Cholera left one hundred and twenty thousand dead. Civil unrest at Saint-Méry pitted common folk against soldiers. The Duke of Reichstadt’s brief candle was snuffed out. Caroline of Naples found herself in chains. A four-power alliance drove wedges between the courts of Paris, London, Lisbon, and Madrid. As Fieschi’s infernal machine shook Juvigny, the would-be regicide became Agénor’s unlikely hero—such was his visceral contempt for the younger branch of royalty that from 1830 onwards, he kept a plaster likeness of the bourgeois monarch in the most degrading position imaginable: in his privy, directly above the most undignified fixture.(105)

The years touched the Marquis only lightly. Slender and unwrinkled, he bore with unassuming dignity the inner pride of possessing talents rarely gracing mere humans. Gone were days when weeks stretched endlessly. He had developed great fondness for Monsieur de Caristy.

Remarkably sturdy for seventy winters, his cornelian snuffbox miraculously unscathed despite countless frenzied pirouettes, the old gentleman had preserved both character and penchant for well-worn tales. The soldierly ways once kept private had, one morning, given rise to fondness for uncomplicated affairs of the heart. Of his friend, whose estate he managed scrupulously and whose spiritual convictions he honoured, nothing bewildered him quite so much as the lavish almsgiving and baffling appetite for ancient bric-à-brac.

Years ago, Agénor had entrusted his daughter to the Montégriers. Having grown merry in idle twilight years, made merrier by selfishness and convenient forgetfulness, they delivered her to his estate for a month each summer. He observed in Berthe a fair prettiness, yet found no shadow of her mother in these evolving features. Unable to alter his nature, he soon felt oppressed by this trio who made him uncomfortable with misplaced joviality, blindness to the past’s value, their habit of falling silent when he approached, yawning early yet retiring late, insisting on plucking every flower before it could die naturally, and visiting the chapel only on Sundays, where what remained of Thérèse had surrendered to the grave’s universal corruption.

Each passing day, Agénor fell deeper under his wife’s spectral thrall. Like matter transmuted into ideal form, he had become progressively refined. His metamorphosis began with subtle signs: touches light as angels’, slender hands suddenly intertwining with his, dreams blossoming beyond ordinary experience, gradually unfolding visions, magnetic sensations of being enveloped—all remaking him, bestowing previously unknown senses and insight. By imperceptible degrees, in particular states of intellectual solitude, whether during blazing afternoons or chill grey seasons, the phenomena intensified: unceasing enchantment, more frequent appearances, soul-journeys to that distant epoch for which the Marquis maintained unquenchable thirst. Nowadays, the moment he found himself free from intruders, Thérèse would manifest and bewitch him, palpably present in the youthful loveliness of their wedding day.

Winter had again despoiled Juvigny of autumnal finery, locking everything in ice. With troubled thoughts, Agénor took his evening meal, soon withdrawing to his chamber—a vast, elongated room awash in moon-like clarity from a high-mounted globe lamp. No servant would enter again, for his sleep-inducing concoction already sent wisps of steam from a thick, ornately chased goblet on the table’s edge. The room, with weighty varnished furniture, had walls draped in white silk rep embroidered with gold-outlined chenille, hung with portraits: Court ladies and long-haired gentlemen with elaborate lace cravats. An open bed squared off a raised platform, lavishly appointed with petit point depicting Louis XIV period figures. Knotty logs crackled in the hearth—distinguished by a red marble medallion encircled with acanthus leaves—sending brief flashes to mingle with the lamp’s serene illumination, playing across authentic seventeenth-century seats where pale violet velvet fleurons twisted against saffron upholstery.

The Marquis washed hands and mouth, slipped from pleated frock coat into cashmere dressing gown. Donning slippers, he arranged his hair, carefully combed his circle beard and slender moustache worn for some weeks. The moment he drained the goblet, eyes alight with anticipation, he spotted the awaited vision opposite: a patch of cloud-like substance suffused with fire’s crimson light. Rippling greenish, it gradually solidified, resembling an unfinished statue. Obscuring the fireplace heart, whose radiant halo maintained wavelike upward movement on either side, the cloud grew denser, forming, whirling, taking richer hues. First came a face helmeted with temple curls, then one bare arm, another, finally the rosy tip of a dainty silk-clad foot beneath triple tiers of pinkish flounces. Thérèse lived again, exactly as in days gone by.

With fabrics rustling softly, she seated herself. He tenderly kissed her brow and eyes.

Not a single shudder passed through the Marquis, nor any trace of misgiving. Nothing but sweet fragrances suffused the room’s warmth as ethereal music drifted from afar.

Gentle breaths caressed his ear, murmuring, “Dear Agénor.”

His attention was elsewhere. The sight of Thérèse, released from tomb and Paradise, provoked happiness so intense it was nearly painful. Without lips parting, they began conversing through silent means. Meanwhile, moon-like light hung motionless and knotted logs flickered with dancing flames.

“I love you!… I love you!”

Thus spoke ghost and living man. This refrain, with infinite variations, gnawed the space between them, enveloping Agénor entirely, dissolving traces of his insular existence. To what ultimate purpose was he drawn? What bizarre madness made him its helpless victim? What beliefs taught that love could shatter death’s barriers, sway Fate’s hand, unite heaven with earth, intrude upon eternal sleep? Not a trace of concern troubled him, constructed as he was for passion, utterly convinced he truly saw, heard, touched, and sensed.

“I love you!… I love you!”

Her eyes resting lovingly upon him, Thérèse lifted his soul heavenward as their perfect union’s hymn answered the distant melody. The memory of that day’s confession had vanished completely. He had wished, not for the first time, to disseminate his joy, revel in modest pride, celebrate the pure miracle granted him. But again memory played false, some inner voice reminding that Monsieur de Caristy had been merely tolerated during those first frightening moments.

“I love you.”

The wretched man kept returning to these words. Drifting through ethereal domains, he became drunk on luminosity, chased phantoms, found himself panting from releasing the purest distillation of his affections. Myriad ways opened, overseen by glimmering dream-stars, where conviction fed upon the occult, gnosis, hope, and yet-unrevealed sweetness. He heaved a soulful sigh, nearly leaving earth behind.

“I love you.”

Yet because the domains he wandered were not those of perfect purity, his baser nature grew increasingly weary and finally halted, despite attempts to urge it onward. “Man is but clay,” and thus fated, even from loftiest heights, to topple precipitously into some miry pit.

“I love you and no other, only you.”

The Marquis regained his bearings briefly, though still pulled in two directions. Then he broke down completely, weeping for the whole of Thérèse he had lost.

The divine symphony had just died away, leaving the once-healing vapours utterly bereft of perfume. Now solemn and still, the dead woman’s apparition hovered, wrapped in rosy corporeality. Her lovely sibylline eyes closed, phosphorescence shimmering on arms and bosom. She spoke no more to Agénor’s mind as he remembered how his wife looked when she came to him, joyful in surrender.

In his mind, he relived their wedding night in distant Paris, hidden deep in winding streets, and all their nights afterward—far too few! He lost himself in recollections of this good-natured, loving, ever-helpful companion, to whom he had been closest friend and protector. Waves of warmth washed over him at memory of that adorable body once his but which he would never touch again. All the yearnings held in check, all that masculine vitality confined during widowhood, now began surging unstoppably, like high tides creeping up an estuary.

A nightmare, that pregnancy! The ghastly, merciless bleeding, her death—all nightmares! And Berthe, those visions—nightmares all! Not a cherub, no—Thérèse lives, for didn’t he hold her, kiss her yesterday? She is love itself, pleasure incarnate, the quenching of thirst. She’s become the spectre breeding deadly thoughts.

On his knees, the Marquis lunges for the apparition. His hands close on emptiness. She’s gone. The globe lamp casts steady pallor, the hearth gives dimming halo—her presence interrupts neither.

Weeping, Agénor bombards emptiness with frantic prayers, twists his hands, howls sorrow, falls numb. At last he sheds clothes and sinks into bed. Sleep comes fitfully, as to a child whose tears poison dreams.

Will they come as tormentors, cruel visions prolonging this wretch’s misery stretched alone in his too-empty bed? Or might they, led by kind yet imperturbable force, try diverting his thoughts whilst keeping their gloom?

First emerge billowing clouds—blue, green, yellow—shot through with rays, speckled with glittering sparks, swirling into single mass. Glowing, flashing, dispersing, drifting—delightful mirage, taste of what’s to come. Then stark scene: whitewashed walls, giant crucifix lit by ox-eye window, where figure lies prostrate, clad in white cotton, forehead wrapped in cloth, under pleated Carmelite robe. La Vallière(106) did penance for loving a king. In prayer she kneels, wretched and drained by helpless jealousy, features gaunt, mouth soiled with dust from countless prostrations. Holy terror has rendered her mute. Love and forbidden joys, jewellery worn, past festivities, violet-perfumed wiles to keep lovelier rival at bay—all now seem sinful to eyes that once sparkled so brightly. Has God forgiven her? Yes, comes Agénor’s dream-voice, loud and clear. His breathing grows laboured as anguish spins into madness, dredging up past, growing ever more acute with each suffering witnessed, each illusion dangled before him.

Now, as if hidden helmsman guides him unchecked through favourite eras, second vision appears, less suggestive of physical union: open sea—indigo depths stretching endlessly, skimmed by frothy waves beneath torrents of golden sunlight. Two armadas prepare to clash, sails catching wind, gilded sterns and prows glinting, magnificent as rival flocks. Flags snap—here fleurs-de-lis(107) on white fields, there tricolour flags of blazing orange, shimmering silver, cerulean blue. Ruyter(108) and du Quesne(109) launch their attack. They mesh, pull away, rejoin the fray, each ship locked with enemy. Billows of smoke and thunderous blasts pour from flanks, sails ripping open, hulls grinding, masts splintering, frayed rigging swinging wildly. Sailors’ cries rise above din, and at slap of stray cannonballs, salty sea splashes skyward.

But the Marquis remains unmoved. He cries out for Thérèse yet again.

“By all that’s holy, my children!” comes sudden bellow by Agénor’s ears—he’s forced to listen—”this ain’t time for dilly-dallying, damn your eyes! No time to fear these Turkish dogs besieging us! Let’s laugh instead as we tan their hides, loot their treasure, woo their Turkish women who’d tempt saints to sin. So get ready for plunder, hit them hard, and long live the king, damn it all! Forward men!”

Astride black charger Phoebus, the Duke of Beaufort(110) preens—proud of rousing speech and victorious curl of moustaches—his entourage of armoured officers around him: Navailles, Vendôme, de Villarceau, Schomberg, all sporting woollen caps. Blades swing from leather belts, pistol grips jutting from uncovered holsters. Three hours past midnight on open square in Candia, rough with cacti and sweet-smelling heather, men Louis XIV sent to serve the Pope stand in battle array: musketeers, seasoned officers, guardsmen, marines, select companies of infantry and cavalry—small band of warriors, arms giving dull gleams, insignia hardly visible under inky sky. This handful sets off, passing beyond city walls—and Agénor finds himself transfixed by Henri IV’s grandson. His heroic end never made the annals of history.

On he marches, crimson plume bobbing on helmet, as blood-red nimbus of rising sun appears behind hill chain, soon lighting gold trim on old-fashioned breastplate, brown buff coat, and—towering above wide boots edged with purple saddle cloth—brilliant scarlet velvet breeches.

“Whoa there! Easy, Sky-Dash!” he cries suddenly.

A massive russet greyhound springs to his horse’s muzzle, snarling, bringing steed to abrupt halt.

“What’s gotten into you, Sky-Dash? What’s wrong?”

After single bark, beast drops head and falls into step, loping alongside with long, intent strides.

“Our doom is at hand,” Beaufort remarks matter-of-factly.

With bearing of Hercules, he pulls upright, features brightening with sardonic grin.

Daybreak brushes pink laurel blooms, warming heathland until scent unwinds from plants, casting golden sheen over palm fronds, meadows, crags, sprawling plain beyond. Throughout landscape, columns of armed men—foot and horseback—create living mosaic of scarlet and azure. Not far, high command makes impressive sight, resplendent in armour catching light in dazzling sparkles, crowned by richly coloured plumes dipping and rising with elegant rhythm. Their ceremonial sashes—painstakingly embroidered in peaceful Parisian streets—billow softly in morning breeze like silent witnesses to unfolding history.

The grave paleness of puppet-like figures tells Agénor everything—battle will soon be joined.

Sure enough, storm breaks loose.

From afar comes clatter of muskets, soon joined by heavy cannon thud. As sun heaves above hills, it sets newly revealed vista ablaze, as if master illusionist conjured it with flick of wand. Amidst pounding drums calling advance and sharp whistle of fifes, standing tall in stirrups, Beaufort—with glance full of noble purpose—raises sabre high, etching brilliant arc across blue-washed sky. The troops surge ahead double-time, emptying landscape in their wake.

Nothing exists except brutal human maelstrom—grumbling, bawling, fizzing, with pauses seeming to hunger for blood.

His troubled fancy leaving him adrift, Agénor loses all sense of place when, piercing momentary quiet of sky animated by swallows, there comes amidst lush thickets and summer crowns of crimson-stained trees, a monstrous blast. Violent tremor runs through his frame.

Immediately, voices lift in alarm, sustaining pitch as they draw nearer. The earth rings. One makes out pounding hooves and sporadic musket crack. Then figures flood into view: men wearing silver-crossed tabards(111) on horses seeming to take wing; horsemen in grey, poppy-red, purple, hunched low over saddlebows; riderless horses whinnying in panic; commanders, ensigns, lance corporals, mass of lesser ranks—misshapen, motley crowd, horde whipped by terror, united in desperate need to be heard as they scream: “Turks! The Turks!… They’ve mined the island!… Run for your lives!”

But hold—what wonderment plays across Agénor’s slumbering face? The roar of commotion still pounds his ears, goosebumps cover his skin, piercing desires well from deep inside. It is Beaufort he gazes upon under sky blazing like forge—captive Beaufort, hatless, dragged by chains, bereft of sword and breastplate, yet contemptuous still. Dauntless Beaufort, body patchwork of wounds, wig singed to half-size, hands and arms bleeding so copiously that at his feet two puddles shine, from which his great russet greyhound slakes its thirst.

All around, yet standing well back, gathers great mass: combatants with green-turbaned heads, wielding spears or clutching guns, perched atop thick-maned Barbary mounts; men on foot with bronzed complexions and obsidian eyes, attired in baggy breeches and short jackets in riot of colours; scattered throughout, bands of slaves, mere bundles of rags, straining at leashes holding monstrous hounds—thirty in all, dull gaunt creatures with wild aspects, built like wolves.

Some dogs howl at top of lungs, smelling blood from afar, whilst others lie prone, more patient by nature, shooting sly looks in all directions.

Here and there, Barbary mounts kick and prance nervously, hides damp with sweat, as handlers work to soothe them. Every sixty seconds sees crowd enlarged by newcomers.

Someone raises arm, shadow stretching immense proportions. Guttural commands travel swiftly round great ring, lip to lip. Dogs are set free. They charge ahead.

First come four or five trembling packs, rushing across sun-drenched ground, stirring spiralling dust devils. They converge on prey, unify ranks, hesitate heartbeat, voice bloodlust, expose fangs, ring Beaufort with low seething wall of flesh. Then, in one collective jump, they launch themselves.

Every hair erect in alarm, Sky-Dash fights to safeguard master. Beaufort, with fettered fists, resists best he can, wielding chains as weapons, delivering powerful kicks. Yet he soon falls, alive but rapidly torn apart. His faithful hound has perished.

Seeing this, Turks edge closer, craning for better view.

“Thérèse… Oh! Thérèse…” whispered the Marquis de Cluses.

Fleeting moment, slight pause of spiritual calm washed away horror, engagement, and anguish of atrocity just shown.

“Thérèse!”

For what purpose rouse him again, when sleep lingers on sole fixation, with same fever of love!

And as more anticipation would only heighten neurotic state; and as he prized above all this phenomenal illusion, this hybrid creature, tender spirit that could make itself corporeal—in an instant, Agénor fancies encountering Thérèse again.

She slips from garments, uncanny, gaze sorrowful, alive, blushing once more but with exceptional tinting—fair and fragile, etched against smoky shadows.

She lifts delicate shoes, skims lacy stockings, which evaporate before his eyes. Bodice falling from shoulders, pastel-like bust reveals livelier velvet quality, lavish fullness. As corset boning parts and disappears like barely visible stain in air, shimmer of flesh emerges between folds of fine batiste the boning had held tight. Her skirt with triple-layered frills is no more.

Agénor feels his very being liquefying.

Before long he perceives loving figure gliding beside him, burning, pulsing, giving itself over. Then, moment of perfect, fathomless oblivion—as if dead woman, overtaken by pity, had finally let herself be defiled.

Never again did the Marquis see Thérèse after that memorable night. Three whole months passed without faintest manifestation—no whispered thoughts, no enigmatic reflections, not even most insignificant trifles. Was he being chastised for descent into baseness that evening of lust? Had the force watching over deemed itself too tempting, too dangerous? None can say.

At first only disheartened, he took to frequent horseback riding, tried losing himself in books, attempted with troubled mind to interest himself in newspapers, methodically re-examined miniature treasures in display cabinets: timepieces, tobacco boxes, enamelwork, jewels. But as fortnight stretched—cold, snowy, weighted with frozen hopes and fruitless supplications—he developed sensitivity of touch-me-not plant, nerves stretching taut at faintest whisper, gaze becoming both darkened and searchingly vigilant.

“It’s over! She’ll never return!” he thought with profound grief.

He grew increasingly unkempt, plagued by regret, crushed by ennui. Abundant tears would gather along lashes, then trickle ceaselessly onto cashmere dressing gown. When merciless need for activity gradually overtook him, château’s domestics started keeping watch.

Indeed, madness seized the wretch after enduring eight weeks frittered away bemoaning fate, chasing same shadow, circling within narrowest confines. He would take to bed only when completely stiff with pain; sleep only when drenched in sweat of complete exhaustion.

“Thérèse… Has anyone seen Thérèse?” he would demand of whoever came close.

It fell to Chevalier de Caristy to nurse him through this period.

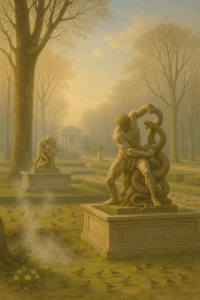

Meanwhile, harsh winter cold began relenting. Gentle warm breeze began blowing, infusing tree trunks, branches, twigs with supple sap. Primroses dressed in new foliage. Between occasional, now less violent downpours, sunlight warmed park mosses enough to release thin vapour tendrils. Swarms of sparrows invaded square-shaped lawns where two olive marble basins were made impressive by great serpents locked in eternal struggle with Herculean figures.

Agénor finally ceased repeating his stubborn question.

Though spirit still grieved, he was healing, had stopped using every moment to distract from sorrows.

Left to himself at last, sprawled on chaise-longue one afternoon, thoroughly enjoying season’s first heat, windows flung open, indolently daydreaming, someone brought him a letter.

The message was from Countess de Montégrier, Count, and Berthe, declaring intention to visit shortly.

At once, he understood this untimely, unforeseen visit’s purpose: My daughter has turned seventeen… A suitable match has been found… Monsieur de Prahecq… In his mind’s eye, he assembled this Monsieur de Prahecq: dark-haired, uninspiring, with career diplomat’s face betraying nothing whatsoever.

His valet’s footsteps had barely been consumed by all-devouring silence when the Marquis—with understanding permeating consciousness as effortlessly as breathing—began assessing proposed suitor’s financial status, considering connections and influence, standing of house, northern roots.

“She’s returned—Thérèse is here again!” flashed through his mind.

He called her name. No form materialised to shadow limpid surroundings or scattered pools of sunlight. Yet when faint whisper of breath suddenly reached him with the words “It’s me!” a hesitant joy stabbed through him—a joy whose feverish intensity he only managed to temper when he became certain of no longer being abandoned, after further signs had made themselves known.