The thirty-one years since the Marquis de Cluses reclaimed his mysterious power—by virtue of the tender feelings he evoked and the grief that overflowed from him—have witnessed the violation of human conscience, the weaving of numerous conspiracies, and the corruption of many truths.

The bond between the ageing marquis, now in his eighties, and that beguiling, ever-changing spectre knows no exhaustion. Together they wander, scale the heavens, frolic, and delight in one another.

From the wars in Italy, Syria, China, and Mexico to the Prussian conflicts; from the fallen Second Empire, Bazaine’s surrender, another invasion, a fledgling republic, and the rechristening of Alsace and parts of Lorraine, to the bloody days of the Commune; this age of ours—ostensibly peaceful yet seething with hatred—in which Europe’s nations bristle at one another, and within each country’s borders, half the citizens would readily slit the throats of their countrymen; Chambord, that honourable Chambord, who met his end at Frohsdorff; the Prahecqs—the Marquis de Cluses remains utterly untroubled by any of this; these are merely affairs of the mortal world. He has been guided away from such concerns; only his obsession with Louis XIV is permitted to flourish(172).

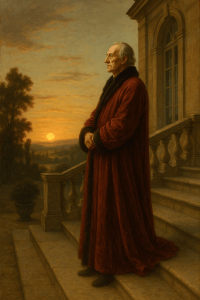

In the wintry season of his life, he has become a recluse within his château walls, dispensing with conventional clothing in favour of draping himself in robes of Armenian fashion.

He lets his hair grow wild and long, partly from a love of simplicity, but primarily as a declaration that he considers himself a stranger to the time in which he happens to be living.

A notary from Juvigny administers his enormous wealth—now increased fivefold—and takes responsibility for dispensing Agénor’s generous alms.

Four servants alone remain in his household—time-worn, silvery figures whose loyalty to their master has never faltered.

Unable to properly maintain the grounds, to wage tenacious battle against the workings of fertile dusts and the summery whims of nature, the grounds have run riot, greened themselves with innocent abandon, while the once-manicured park has rewilded itself into woodland, becoming a prolific sower of seeds; unbidden shrubs have thrust themselves upward; overgrown paths now substitute for the formal walkways where, across generations, the exquisite figures of Jenny de Cluses, Thérèse, Berthe, and Laure had once regally trod upon fine sand, resplendent in their blue or yellow skirts in the fashion of Ipsiboë(173), lilac bodices, and pink shawls, rivalling the floral splendour of the garden beds.

The Marquis, however, cannot quite manage to die, as if some force were putting him to the test—as if he were being punished for refusing to be a common sort of man, a real man: self-indulgent, cowardly, power-hungry, crafty, envious, cynical, bestial, and bloodthirsty.