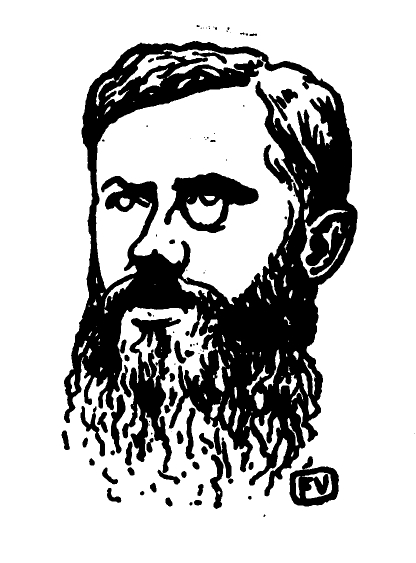

Portrait of Édouard Dujardin (1861-1949)

by Félix Vallotton, 1898

.

The following text presents selected chapters from Édouard Dujardin’s Mallarmé, par un des siens, published by Messein in Paris in 1952. To my knowledge, this book has not been translated into English.

.

MALLARMÉ

.

It is well known that Mallarmé was born in 1842 in Paris to a family of civil servants with roots in Burgundy and Lorraine, that he pursued his studies in Paris before attending the lycée in Sens. There he formed a friendship with one of his professors, Emmanuel des Essarts, who was only a few years his senior and who introduced him to the young poets of the Parnasse movement.

After some time in England, where he married, he became an English teacher, first taking a post in Tournon from 1862 to 1866.

Mallarmé’s remarkable precocity has never received adequate recognition. By twenty, he had already written some of the poems that would later appear in Le Parnasse contemporain. We know from his letters to Aubanel that by twenty-two he was working on Hérodiade and L’Après-midi d’un Faune, and that only two years later he had conceived the outline of what would become his life’s crowning achievement.

As for L’Après-midi d’un Faune, Mallarmé began its composition at Théodore de Banville’s invitation, intending it for Coquelin, who was eager to add verse monologues to his repertoire. “The verses of my Faune,” he wrote to Aubanel in 1865, “were met with boundless enthusiasm, yet Banville and Coquelin found them lacking the kind of storyline the public craves, and told me that only poets would be interested. So I’m putting the piece away in a drawer for a few months, planning to revisit it more freely later.”

The original manuscript of this first version of L’Après-midi d’un Faune (then simply titled The Faun) belonged to Madame Ernest Chausson; Paul Valéry, Henry Charpentier, and I each possess copies. This early version presents a markedly different state of the work from the final one. The public will someday appreciate its considerable interest when the heirs allow its publication—or, in any case, when Mallarmé’s works enter the public domain.

From Tournon, Mallarmé was transferred to Besançon, where he stayed for a year, then to Avignon, where in August 1870 he received a visit from Catulle Mendès and Villiers de l’Isle-Adam—we shall speak of this later—and from there he moved to Paris, appointed first to teach at the lycée Condorcet (then known as lycée Fontanes), then at Janson de Sailly, and finally at the collège Rollin. It is profoundly saddening to think that this career, which he pursued for the full thirty years required, weighed so heavily upon him. As early as his time in Tournon, he shared these complaints in his letters to Aubanel, and those closest to him remember how, in the privacy of trusted conversations, he continued to voice these same frustrations in Paris. Thus his first lesson, his first example to us, was that a poet must be willing to take on even the most trying professions if that is the price of independence.

The 1876 publication of L’Après-midi d’un Faune, illustrated by Manet—whom Mallarmé had befriended—drew some attention to his name, a recognition soon heightened by Huysmans’ À Rebours and Verlaine’s Les Poètes maudits. Then, in January 1885, Prose pour des Esseintes ignited a kind of fame built as much on ridicule and insults from the many as on the devoted, almost filial admiration of a select few.

Around that same period, in 1884-1885, young poets who became his disciples began attending his Tuesday gatherings at his home, 89 rue de Rome. I made his acquaintance in the autumn of 1884, and from that moment forward, the brief account I present here will be that of a witness.

I had written to ask for his collaboration on the Revue Wagnérienne, which was then in preparation. He gave me his word, and the following summer sent me the substantial article “Richard Wagner, Rêverie d’un poète français,” which is perhaps the most thorough presentation of his doctrine. Then, in January 1886, came the celebrated sonnet to Wagner. Throughout 1886, the preparations for the Revue Indépendante, where he was to be a regular contributor, brought us into even closer contact. He had taken on the role of dramatic critic, hoping to articulate some of the theatrical ideas he had been sharing with us during our Tuesday meetings. This led to the series of articles—so vital for understanding his work—that he later gathered, with some revisions, into Divagations.

By a contract dated February 13, 1887, and carefully transcribed (on stamped paper!) by the somewhat clumsy hand of the Revue’s page boy—a copy of which I still hold—he granted me the right to publish a popular edition of L’Après-midi d’un Faune. The following year came the offprint (which he particularly wanted to be well-crafted) of his translation of Whistler’s Ten O’clock. Yet the most significant contribution to the Revue Indépendante was the autograph edition of his poetry, spread across nine instalments, each bearing an ex-libris by Félicien Rops, with a print run of just 40 copies at 100 francs apiece. This edition, which appeared between 1887 and 1888, is now highly prised. However, it’s worth noting that despite its value today, it found only a modest number of subscribers, and half the copies were sold for a pittance when the Revue Indépendante collapsed—or rather, changed hands—at the end of 1888, failing to secure enough subscribers to stay afloat.

During those three years, my interactions with Mallarmé were constant, especially as he often entrusted me with small, non-literary tasks, and I received from him a great number of notes, none of which—no matter how brief—could ever be considered insignificant. These exchanges continued, though less frequently, in the years that followed, during a somewhat tumultuous period in my life. He stood by me with his presence and encouragement when I staged the three parts of Antonia. He brought Whistler to the second performance in 1892, and the article he kindly devoted to the final one in 1893—later reprinted in Divagations—became a defining moment of my literary life. May I add that in 1896 he agreed to be a witness at my first wedding, alongside the painter Raffaelli and my friend Aristide Marie. I vividly remember how, on that occasion, he took great pleasure in lingering over lunch in what had once been the bathroom of the Hôtel de la Païva, now turned into a restaurant by the famous chef, Cuba.

On the recommendation of the art critic Burty, he had discovered, not far from Fontainebleau, on the banks of the Seine, a small farmhouse in Valvins. He rented part of it, and it became both his refuge and his joy. It was here, in 1893, that he settled permanently after retiring. Having made my home in the Fontainebleau region as well, I was fortunate to be in close proximity to him, alongside his neighbour, Elémir Bourges.

It is well known how he passed away almost suddenly in 1898, at the height of his maturity. Those of us who were there will never forget that radiant autumn day when we, with heavy hearts, accompanied him to the small cemetery of Samoreau, where he now rests.

To those who had loved him, and to all those who continue to love him and will love him even without having known him in person, Mallarmé left behind more than just his written works, more than the body of work he had shared with us, and more than his ideological and literary teachings.

Indeed, the name Mallarmé calls to mind the names of great thinkers like Socrates, or perhaps more fittingly, those founders of religions whose legacy lives on not just through their writings, but through the memory that endures, carried in the hearts of their followers.

The Tuesdays we spent faithfully gathered around him have been recounted many times, but I can think of no better way to share their spirit than by gathering the echoes of those moments from a few of us.

The memory of those gatherings on rue de Rome, as Bernard Lazare wrote, will always remain with those privileged enough to be welcomed by Stéphane Mallarmé into that subtly lit salon, where shadowed corners lent the room the feel of a temple, or perhaps more fittingly, a chapel… For his devoted listeners, Mallarmé possessed an endless charm, whether he delighted in recounting an anecdote, let himself drift into memories of dear friends now passed, or laid out his captivating and lofty views on poetry and art.

Conversations would spring to life with ease, as Albert Mockel described it. Without any affectation and with thoughtful pauses, they would effortlessly drift to those higher realms that meditation so often explores. A gentle gesture would add to a point or lend emphasis; our eyes would follow his own, beautiful and calm like those of an older brother, with a refined, quiet smile, and at times a certain mysterious solemnity. Those were unforgettable hours, surely among the best we would ever know, as we found ourselves, amid all the grace and allure of his words, immersed in the pure reverence for ideas that brings the mind a kind of spiritual joy.

A word still from Henri de Régnier:

It was within these humble walls, on certain evenings of spiritual festivity, that the most refined and profound words were spoken about life, art, and poetry—where the two meet and become one. In that place, we listened as a rare meditation unfolded in precious phrases, with fundamental themes and delicate embellishments, all for a few who could catch a glimpse of its wonder—a vision among the loftiest, most beautiful, and most remarkable reveries of humankind. Moments, alas! that can never be relived, yet are unforgettable for those who witnessed that memorable nocturnal scene, that solemn consultation a man has with himself, grappling with his own doubts or lost in the ecstasy of his certainty.

A silence would fall; then his solemn gestures would ease back into familiar warmth, the marvellous sketch would disperse into lighter drafts, and the grand theories would be draped in delightful anecdotes, exquisite in their grace or sharp in their wit, each worthy of a laugh, gentle and restrained.

André Fontainas and Robert de Souza lamented the day when the small room on rue de Rome was invaded by crowds of interlopers. This could only have happened in Mallarmé’s later years, when his fame had fully blossomed. Back in the earlier, more heroic days—around 1885 and the years immediately following—it was just us, a close-knit circle. I can still picture us gathered as if in brotherhood, or rather like sons, seated around the table while he stood by the fireplace… Certain names come easily to mind: Rodenbach, Gustave Kahn, Laforgue, Saint-Pol Roux, Fénéon, Charles Morice, Ajalbert, René Ghil, myself, Wyzewa, Merrill, Vielé-Griffin, Henri de Régnier, Mockel, Herold, Fontainas; Moréas was seldom there; later, Gide, Pierre Louÿs, Valéry, Paul Fort, Claudel, Robert de Souza; along with Claude Debussy, Paul Adam, Barrès, his cousin Victor Margueritte; and a few others whose faces are now a blur; sometimes even foreigners passing through Paris—Stefan George, Arthur Symons, John Payne, Charles Whibley, Houston Stewart Chamberlain—all discreet and respectful. Villiers and Whistler would break into laughter now and then, like brief interludes that never disrupted the communion. Rarely did we see outsiders like Octave Mirbeau, Hérédia, Théodore Duret, and the dreadful Oscar Wilde, whose presence was met with a silent disapproval on our part that ought to have taught him one did not come to Mallarmé’s to hold court.

The fate of new religions tends to follow a predictable course: once the master is gone, the followers scatter. Some build small chapels of their own, others withdraw into solitude, and still others blend back into the crowd. Yet the new religion remains alive. Why? Because, for all their differences, the disciples share one enduring bond—the memory of their master. Sometimes this alone provides unity for a fledgling religion.

In 1917, a French poet—whose name I will spare you—wrote in a Swiss newspaper that Mallarmé was a poet of art for art’s sake… What a mistake! What a fundamental misunderstanding! And how ungrateful!

In a recent book, Camille Mauclair writes that “Mallarmé’s heroism consisted in this: that, in order to preserve a dream he felt burning inside him like a shard of radium, he resigned himself to being unfit for any profession or initiative, to enduring all the humiliations of discomfort, all the insults of public disapproval, to battling against what he recognised in himself as sensuality and preciosity, aspiring only to the absolute, and, with a silent, indulgent, yet infinite contempt, excluding the temptations of commercial literature that were offered to an outcast like him.” This is perfectly expressed and entirely accurate; but this dedication to his dream, this acceptance of hardship, this rejection and disdain for ordinary satisfactions—these, as I was saying, are the first lessons and examples he gave us. It must be said (and it’s a great comfort to remind ourselves) that his dedication was rewarded by the inner joy that must have come from the reverence we surrounded him with. And after all, others had given such dedication before him, and others will give it again. Mallarmé’s true legacy lies in showing how the highest intellect can be united with the highest goodness and the noblest teaching in a poet.

As for me, of all the men I have encountered over the past half-century, those who have stayed alive in my memory—those I have shared my worries and joys with, brothers in arms from my youth, humble collaborators in the daily grind, illustrious elders like Villiers, Huysmans, and Verlaine, and fleeting but unforgettable appearances (Hugo at his window, Wagner pacing the corridors of his theatre)—one stands above all others; one, more than all the rest, continues to accompany my thoughts; one, more than any other, offers guidance, approves with a smile, or gently reproves with a look that turns away; supreme kindness and understanding; one more than anyone else to be the great, deep friend, as much as any demigod might be your friend, but so much more the guardian angel! And so much the divine worker who pulls the weeds and sows the good seed, the living example of what is beautiful, what is good: Mallarmé.

And I still find myself thinking.

Of all the writers and musicians I endlessly revisit in books, and whose music I hear again at the theatre or in concert, of those I may have perhaps loved too much, having listened to them too often, of those whose verses or melodies still echo in my memory, of those whose doctrines still carry me into a sort of metaphysical rapture, one is almost never present: Mallarmé. He hardly ever comes, except through a few lines from Divagations, which are but the faintest echo of his voice. Yet L’Après-Midi d’un Faune remains a great masterpiece, and those sonnets! Why, why do their verses stay so far from my meditation, when his spoken words, his smile, his handshake, his example remain so close, always?

But what Plato will ever capture this Socrates? Which quartet of evangelists, this Jesus? Alas! All we can do, when we speak of him among ourselves, is understand each other through our gaze, and murmur to the young who listen to us words almost incoherent, as if choking on the voice. And yet we must try to leave behind something of our love. But when we have passed through the gates, will those who come after us sense, from our faltering, which saint watched over our youth?

.

THE WRITTEN WORK, THE DOCTRINE

.

The body of Mallarmé’s written work is easily tallied: a small number of poems, the most complete edition being the one published under the title Poésies by the Nouvelle Revue Française, though it suffers from the irredeemable flaw of not following chronological order—the only sequence that truly reflects the development of the poet’s thought and technique; along with a few prose poems and a handful of articles collected in Divagations (Fasquelle, 1897). In addition to these two volumes, which would encompass the bulk of his work—if only the Poésies included Coup de dés—there are occasional verses gathered in 1920 (Nouvelle Revue Française), translations of Poe’s poems (reissued by the Nouvelle Revue Française), Whistler’s Ten O’clock (Revue Indépendante, 1888), and lectures on Villiers de l’Isle-Adam (Art indépendant, 1890) and on Music and Letters, 1894 (Perrin, 1895).

To truly grasp this work—and just as much the one he never finished—it’s essential to examine the doctrine he laid out in his conversations and articles.

This teaching, his doctrine of poetry that defines him ideologically and remains the most contested part of his legacy today, springs from two core principles: one, captured in the famous phrase, “All that exists in the world is destined to end in a book,” which, in simpler terms, suggests that the purpose of poetry is to explain the world; and the other, that things only matter in relation to their symbolic meaning.

Let us try, even at the risk of oversimplifying, to break this doctrine down into its most straightforward elements.

Idealism — For the champions of naturalist prose and Parnassian poets, things were valued only for what they were; the life of a Rougon-Macquart, or a particular scene in Ancient Poems or Barbarian Poems, aimed only to tell a story or evoke those realities as they existed. For Mallarmé, however, such realities were only meaningful as signs, as symbols pointing to other realities of a higher order—the realm of ideals.

It was in this very idealism that Remy de Gourmont saw the defining hallmark of symbolism.

In 1896, he wrote about “a new truth that had only just entered literature and art—a truth wholly metaphysical, entirely a priori (or so it seems), still young, being only a century old, and remarkably fresh, for it had yet to be applied to aesthetics. This truth, at once evangelical and wondrous, liberating and revitalising, was the principle of the world’s ideality. For humankind, the thinking subject, the world—everything external to the self—exists only through the idea one forms of it. We know only phenomena; we reason only through appearances; any inherent truth eludes us, and essence itself remains beyond reach. Schopenhauer encapsulated this perspective in his concise, striking maxim: The world is my representation. I do not see what ‘is’; rather, what ‘is’ consists of what I see. Each thinking individual, therefore, perceives a different world.”

And he continues:

“The only valid reason for someone to write is to write about oneself, to reveal to others the kind of world that takes shape in one’s unique mirror.”

This idealism, as Henri de Régnier later noted, is the metaphysical key to the minds of most thinkers from the generation that formed the symbolist school.

Might I remind you that my first book, Les Hantises, published in 1886, opened with this epigraph: “Only our soul lives.” Could there be a stronger assertion of idealism?

It’s rather ironic, then, to find Nicolas Beauduin expressing nearly identical ideas in a piece written in 1913, but now put forward as a reaction against Symbolism! Clearly, Beauduin had a limited grasp of his predecessors.

Here is the passage in question; indeed, it contains scarcely a phrase that would not have found ready assent among the youth of 1885:

“The new poet,” Mr. Beauduin asserts, “is no longer the mere servant of his sensations; he is, in some sense, the master of the world. This poet reveals the universe through a kind of intuitive illumination. ‘We think the world,’ the Paroxysts declare, ‘and so, inevitably, we recreate it. We are the world, just as it becomes part of us. Its life animates ours, and it dwells within us, deep in our inner vision, engaging directly in our activity…’

For us, nothing exists apart from the soul; there is only the Cosmos, of which the soul remains an eternal part—a homogeneous world, inseparably linked to consciousness. Here, thought and action merge. So there is only one world, an inner one, conceived and willed into being—a world we possess, animate, and constantly exalt, guided by our ever-alert sensibility. This world, in turn, is projected outward, shaping appearances that reflect our psychological states, transmuted by our fervour into heightened, lyrical states…

How far removed we are, are we not, from the old Romantic view of the poet, as Théophile Gautier saw him: A man for whom the external world exists.”

‘Only our soul lives,’ I wrote back in 1886.

How did we, at that time, come upon the principle of the world’s ideality? It was, without question, a Germanic influence. Remy de Gourmont, in the passage I cited earlier, credits Schopenhauer; comparing ideas, and then simply checking the dates, leaves little room for doubt.

Schopenhauer, born in 1788 and dying in 1860, published the first edition of The World as Will and Representation in 1818. Yet it was not until 1874 that a significant French study of Schopenhauer appeared, thanks to Th. Ribot. Burdeau’s translation of The World as Will and Representation appeared only in 1888, and Burdeau had, in fact, taught philosophy to several among us. It was also in 1885 that the Revue Wagnérienne began to bring the great philosopher’s ideas to the younger generation.

This context explains how the symbolists arrived at their unique view of legends and myths.

Poets across the ages have had a fondness for legends and myths. But how did the Romantics and the Parnassians approach them? They told these stories with as much objectivity as they could muster. And the Classics (I am referring to the French classics)? They employed them as the setting for their psychological analyses.

What did the Symbolists do? They didn’t merely recount them; they sought to uncover their deeper meanings, always in search of the idea behind the outward appearance.

Consider, for instance, the myth of Iphigenia in Aulis. Racine presents it as a historical fact; he stages it with the sole purpose of drawing out its human side.

While the Parnassians, to my knowledge, never took on this myth, one can easily envision how Leconte de Lisle would have approached it: an effort to reconstruct primitive customs, with painted armour, names kept untranslated, and a jumble of archaeological curiosities—something that would have felt very much like a “Russian ballet.”

A symbolist would delve into the profound significance of such a human sacrifice, endeavouring to distil its esoteric meaning, but never would it cross his mind to try to remake Euripides… Moréas, over the years, wore many hats; was he a symbolist? Indeed, for a time—a few years, to be precise—before going on to found the Roman school and ultimately converting to classicism. But it was enough to listen to how he spoke French at the brasserie to realise how, despite his indisputable talent, this imitator of all our styles had remained, in essence, a foreigner among us.

As for myself, I recall that in earlier days, older friends—those who adhered to naturalism or parnassianism—failed to comprehend my preoccupation with unveiling the deeper meaning of the myth.

— “Simply recount the tale,” George Moore would often remind me; “explanation veers into philosophy.”

My aim was to write poetry, but it was idealistic poetry, symbolic poetry.

“A divine idea,” as Carlyle put it, “permeates the visible universe… This divine idea, however, is concealed from the crowd… Writers, then, are the chosen interpreters of this hidden idea.”

Mallarmé taught nothing else, and his works stand as the exemplary testament to this belief. He consistently maintained that the purpose of poetry is to express man, not in his selfish individuality, but in his reciprocal relations with all that exists. True glory, he claimed, lies not in the external accolades it commands, but in the very assent that it is.

Thus, Mallarmé’s symbolism, as a literary doctrine, is, above all, idealistic. In this regard, it reveals a second, particularly distinctive quality: Mallarmé’s symbolism was, if I may describe it thus, musical.

Music — For the Romantics and Parnassians, music scarcely held any more significance than it did for the Naturalists: it was, in their eyes, merely one of the “fine arts” that the state was obliged to protect, but one for which they themselves had little passion or concern.

For Mallarmé and the Symbolists, however, music revealed itself not as an art of technical virtuosity—piano or violin concertos, scales, and acrobatics—but as the profound voice of things themselves. This view aligns with Schopenhauer’s philosophy, who states that music alone provides the idea of the universe without the need for any intermediary concept. It speaks of the world as Will—its underlying reality—while the other arts convey it as Representation, that is, in its external appearance. The men of my generation found a magnificent elaboration of these ideas in Wagner’s masterful study of Beethoven, the first French translation of which appeared in Revue Wagnérienne.

The Revue Wagnérienne was founded in 1885 (lasting until 1888), at the very moment when Symbolism was beginning to take flight. If I believe its name will endure, it is because, rather than serving as a mere journal of musicology, it was, first and foremost, a literary publication.

In essence, the Revue Wagnérienne fulfilled a threefold purpose:

- It propagated Schopenhauer’s philosophies, particularly his views on music;

- It illuminated Wagner’s dual nature as both poet and composer—though, in truth, it was no trivial task to make the case that Wagner was, above all, a poet, and one of the finest at that;

- Finally, it was the Revue Wagnérienne, through its director—and I take pride in this—that introduced Mallarmé to the Lamoureux Concerts.

On that occasion, I was accompanied by Huysmans. Take a moment to appreciate how the symbolist’s and naturalist’s minds stand in such stark contrast! Huysmans wrote a page about the opening of Tannhäuser, a clever paraphrase of the programme handed to him by the usher; he had scarcely listened to the music and never returned to the concert. Mallarmé, by contrast, attended every Sunday; and it was from these visits that he drew inspiration for the sonnet on Wagner and the Rêverie d’un poète français.

In January 1886, the Revue Wagnérienne published, as a tribute to Wagner, not only Mallarmé’s sonnet (“Le silence déjà funèbre…”), but also a series of others, including one by Verlaine (a masterwork of his: “Parsifal a vaincu les filles…”); alongside contributions from René Ghil, Stuart Merrill, Charles Morice, Charles Vignier, Teodor de Wyzewa, and myself.

It struck a powerful chord. At a dinner for journalists held around that time, chaired by Auguste Vitu, the only topic of conversation was Mallarmé’s sonnet. Unsurprisingly, they were torn between laughing and being offended. Yet the most remarkable aspect was that half of the journalists present, with Vitu leading the charge, thought it a good idea to memorise it and recited it aloud in unison, word for word.

The influence of Wagner was truly astonishing. No one else pulled myths into such meaningful forms as he did, and it was this extraordinary insight that thrilled our generation: the realisation that The Ring of the Nibelung, this supposed opera libretto, was among the most magnificent “literary” poems ever born from the mind of a human. Its beauty lay in the ceaseless interplay between folklore and human drama, underlaid by a deep philosophical foundation. And as for its poetic “writing”—with what fervour we recognised, bit by bit, in the verses of the Nibelung, precisely the style of verse that resonated with our own poetic yearnings.

In a time when patriotism for many French writers meant blaming every wrong on Germany—during the war, of course—the German influence was brandished against the Symbolists like an insult.

“Perhaps more than even the visual arts,” remarked someone—though I have forgotten who—”poetry has fallen victim to this Germanic intoxication. A choking gas drifts across from beyond the Rhine. Humanity had its symbol; the Germans formalised Symbolism. Too bad for them! And have French poets embraced it too? Well, so much the worse for this chapter of our lives, and for the world at large!”

Charles Morice countered by denying that the Symbolists had any German influence… an unfortunate concession. Neither the war of 1870 nor that of 1914 could prevent a poet, as a young man, from exploring the teachings of Schopenhauer, Wagner, and later, Nietzsche.

In a 1900 article that later appeared in The Problem of Style, Remy de Gourmont reflects on the “ascendancy of Germanic thought” within “recent French literature.” He highlights figures like Hegel, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche, while curiously leaving out Wagner, and remarks that “German influence (1890–1900) has really come to us only through philosophy.” This oversight can be explained both by de Gourmont’s lack of connection to music and, admittedly, by the fact that, with regard to symbolism, he always remained an interested yet somewhat detached onlooker.

Within the realm of Mallarmé’s symbolism, one discerns an aspect of painting, yet, even more vividly, an undercurrent of music. Just as idealism permeates thought, music here permeates both substance and form, idea and expression alike. Mallarmé taught us that verse itself possesses a musical architecture, founded upon rhythm and harmony, while the symbolists went on to weave an array of musical devices into verse—assonance, alliteration, leitmotifs… As Mallarmé so memorably put it, poetry must seize back from music what is innately its own—an idea I intend to examine more closely in the following chapters.

Impressionism — I lack both the time and, admittedly, the expertise (since it would entail discussing painting) to analyse what I consider yet another essential trait of Mallarmé’s style: impressionism. Mallarmé was something more than a mere friend to Manet, Renoir, and Monet; like them, he would have blushed at describing an object as an auctioneer might—he does not depict the object itself but rather the impression it leaves upon him. For example, here’s how he sees the sunlight:

Thunder at the hubs and rubies…

Such impressionistic description stands in for realism, blending instead with idealistic and musical description.

Risen from the croup and the leap

Of an ephemeral glassware

Without flowering the bitter vigil

The forgotten neck breaks off

In this way, Mallarmé (and I borrow Remy de Gourmont’s interpretation) portrays a vase with a tormented belly and sharp neck, overlooked and unfurnished with flowers, which appears, for want of a rose, abruptly broken.

At the century’s end, “impressionism” was reserved for painting, while in literature, “suggestion” was the chosen term. Charles Morice taught that art’s aim is not to describe, but to suggest. Henri de Régnier dedicates several beautiful pages to explaining how rhythmic and metaphorical suggestion was a discovery of symbolism.

Suggestive poetry, impressionistic poetry: there is, of course, a fine distinction between these terms. Yet let us recall that, in any case, Victor Hugo, when Mallarmé was approaching forty, spoke of him as “his dear impressionistic poet.”

The Desperate Attempt — In my view, these are the three discoveries on which Mallarmé’s oeuvre and doctrine are founded.

But it’s here that the challenge truly begins.

Mallarmé’s extraordinary sensitivity, his almost fragile delicacy, led him toward what I can only describe as a desperate attempt: to convey solely the symbolic, musical, and impressionistic qualities of things, while leaving their objective value only hinted at. His aim, in effect, was to express not the things themselves, but only their symbolic resonance, their musical quality, and their impressionistic essence.

An example is necessary to illustrate this.

Mallarmé’s work reveals a steady evolution from the most transparent forms to the most enigmatic, and this is due precisely to his relentless and ever more focused effort to reduce expression to pure symbolism, music, and impression.

Let us examine two of his poems, one from the beginning and one from later in his career, to better grasp the path he travelled:

We begin with one of his earliest works, Les Fleurs, for instance… This poem radiates with clarity; and if there is anyone unfamiliar with Mallarmé’s work, I can almost hear them say:

— Is this the poet reputed to be so obscure?

Then let us move on to a later poem, one far more obscure this time, which we shall attempt—and successfully, I trust—to understand; in doing so, we shall uncover the reasons behind its obscurity.

Consider, for instance, the sonnet: What silk in the balms of time…

Quelle soie aux baumes de temps

Où la Chimère s'exténue

Vaut la torse et native nue

Que, hors de ton miroir, tu tends!

[What silk embalmed by time

Where the chimera exhausts itself

Can rival the twisted and native cloud

That you stretch out beyond your mirror!]

The final two lines exemplify Mallarmé’s technique: “the twisted cloud that you extend beyond your mirror,” with the following quatrain clarifying that this is the hair of the beloved woman, appearing in her mirror like a cloud.

Here, we begin to see Mallarmé’s technique at work. He does not say, “What silk compares to your hair, which resembles a cloud…” Instead, he leaps straight to, “What silk compares to the cloud…” leaving the first term of the comparison unspoken.

Let us examine the second quatrain:

Les trous de drapeaux méditants

S'exaltent dans notre avenue:

Moi, j'ai ta chevelure nue

Pour enfouir mes yeux contents.

[The holes of prayerful flags

Flare up along our avenue:

But I, I have your naked hair

To bury my joyful eyes in.]

This, I think, is clarity itself. Others may delight in gazing at the fluttering flags… but as for me, it is within your hair that I want to bury my eyes.

Non! La bouche ne sera sûre

De rien goûter à sa morsure

[No! The mouth will not be sure

Of tasting anything in its bite,]

Here, “bite” symbolises the kiss, staying true to an impressionistic expression… One can only truly savour the kiss of your mouth if…

S'il ne fait, ton princier amant,

Dans la considérable touffe

Expirer, comme un diamant,

Le cri des gloires qu'il étouffe.

[If your princely lover, in that lush crown,

Can, like a diamond, let expire

The cry of glories he keeps silenced.]

…if your princely lover, in the abundant cascade of your hair, sacrifices the cry of glories he keeps within—in essence, offering the most precious part of himself.

In summary: No silk can measure up to her hair; it is there that the poet buries his eyes. But to taste the kiss of her mouth, he must offer up the most cherished part of his being.

Rémy de Gourmont analysed Mallarmé’s approach in the fourth volume of his Promenades Littéraires. He explains that every comparison is made up of two elements: the thing itself and that to which it is compared. The classics make both terms explicit. The second term is the only one Mallarmé lets us see.

I recall Mallarmé once telling me, “I cross out comme from the dictionary.”

And therein lies the crux of Mallarmé’s method. He no longer says, “This thing resembles that one…” For him, the thing itself has become that other.

This, in a way, is a kind of magic, as the term is understood in the history of religion. In the rituals of witchery, the doll pierced in the heart to bring about the death of the enemy it represents is no longer merely an image of the enemy; it has become the enemy itself. Similarly, for Catholics, the Eucharistic bread is not just a symbol of Christ’s body, but the body itself. This is the mystery of transubstantiation. For Mallarmé, as for St. Thomas Aquinas, the Eucharist exists only inasmuch as it is the body of Christ.

In matters of religion, there are no limits to what faith can demand. In art, however, the rights are fewer.

One only needs to consider Mallarmé’s later works to appreciate the challenges and obscurities brought about by his erasure of the word comme… The sonnet we have just examined, in comparison, seems childishly simple.

Gourmont wrote: “Of the two terms of the comparison, Mallarmé lets us see only the second.” This isn’t entirely accurate; one should say: “Of the two terms of the comparison, Mallarmé describes the first only as the second.”

A classic might say, “The poet is like the sun.” Mallarmé, in expressing what the poet is, describes the sun. He has erased the word comme from the dictionary. But how will he designate the sun itself? In the impressionistic manner. At no cost will he allow the two syllables of the word to appear.

Thunder at the hubs and rubies…

he will say, and we will know that he is speaking of the sun, that is, of the poet himself.

The Decadent Parlance — In literary discourse, it is customary to distinguish between content and form. I, however, take issue with this division, as it often disregards the fundamental interconnection between the two. Yet, this distinction does hold some merit, particularly when, after delving into the thoughts of a poet, one turns to examine the vocabulary and syntax used to express those thoughts. What was Mallarmé’s choice of vocabulary and syntax? This leads us directly to the question of “decadent parlance”—the peculiar jargon that began to gain ground around 1884, reaching its satirical zenith in the parody Les Déliquescences by Adoré Floupette.

Théophile Gautier’s definition of the “style of decadence” is well-known for its brilliance. I cite it here from the study that Henri de Régnier devoted to the “Decadents” of 1885-86:

The so-called style of decadence, in Théophile Gautier’s words, is nothing short of the art that has attained such an extreme degree of maturity, a maturity shaped by the oblique rays of the setting sun that marks the decline of civilisations. It is a style that is ingenious, complex, erudite, rich in subtlety and nuance, forever stretching the boundaries of language, borrowing from every vocabulary, drawing shades from every palette, notes from every scale. It seeks to capture thought in its most indefinable essence, rendering it in contours that are as hazy and elusive as the thoughts themselves. This style of decadence, according to Gautier, is the final utterance of the Word, called upon to articulate all, and pushed to its most extravagant limits. Furthermore, Théophile Gautier remarks, this style, scorned by the pedants, is by no means simple. It conveys new ideas through novel forms and employs words that have not yet been heard, carving out a new path where others have not ventured.

These traits apply fairly well to the language used by the poets of 1885-86, yet I find it impossible to regard this as a mere sample of decadent style. The “decadents” of 1885-86 were not, in fact, poets of decadence.

When we call the poets of 1885-86 “decadents,” we are confusing what was, in reality, a renewal with a form of decline. Since the term has been widely adopted, let us concede, for the sake of convenience, to label the poets of this period as “decadents.” However, we must understand this term as nothing more than a convenient label. According to Théophile Gautier’s definition of decadence, such poets would represent the final offspring of a dying age. But the “Decadents” of 1885-86 were, in truth, the vanguard of a new era. Their linguistic innovations, their bold forays into uncharted verbal territory, were the hallmark of a generation in search of its own identity. A new vision of poetry demanded a new language. Naturally, this new language begins with exaggeration, with eccentricities; and only afterward does it settle into more tempered forms.

This was the case with the Pléiade in the sixteenth century.

It was true of Romanticism.

It was equally true of Symbolism.

For this reason, I have always maintained that there are two phases in the evolution of Symbolist grammar: first, the “decadent parlance” of 1885-86-87-88, an explosion of extreme audacity, which pushed the limits of language from the very outset; and second, what might be termed “symbolist parlance,” a continuation of the former but notably more restrained, carrying over the same peculiarities but divested of the initial excesses. This is the language that, starting in 1889-90, became the lingua franca of poets like Vielé-Griffin (Joies), Maeterlinck (Serres Chaudes), Henri de Régnier (Poèmes anciens et romanesques), and later of Herold, Fontainas, Merrill, and countless others. It is, if I may refer to my own works, the language I adopted from 1891 onward, after, alas! having been mired in the most intolerable jargon from 1885 to 1888.

Having said this, it would be useful to clarify the features of “decadent parlance,” and by extension, but in a more moderated form, the “symbolist parlance.” A thorough study could be undertaken here, but let me condense it into a few lines that will be immediately familiar to anyone acquainted with the works of this period.

Certain elements of this style revolve around vocabulary, while others lie in the realm of syntax. As for vocabulary, we encounter unusual or newly coined words that quickly became synonymous with this school—terms like “navrances,” “errances,” and “luisances”; adjectives or adverbs treated as nouns; and, to single out one curious quirk, the favouritism shown to “en” over its counterpart “dans”!

When it comes to syntax, we see a frequent disruption of the natural sentence order—arguably the most apparent and recurring feature—often under the pretense of mirroring the flow of thought or enhancing specific shades of meaning (illustrious examples of which I will mention shortly). Occasionally, these choices are born of grammatical fixations; indeed, some writers went so far as to claim they were “reforming” the language to reclaim words’ original values! Interestingly, these eccentricities appeared more often in the prose than in the verse of the symbolists. Certain pages of Verlaine’s prose are saturated with them, while his verse is largely untouched.

One need only remember that major literary upheavals tend to incite a blending of the mediocre with the brilliant, as neither the eminent poets of the sixteenth century nor the Romantics escaped this phenomenon. Mallarmé’s language, likewise, may find itself categorised as “decadent parlance” without diminishing the reverence due to the purest of French stylists.

Let us, however, avoid conflating the question of “obscurity” with that of “decadent parlance.” We have just explored the origins and core of Mallarmé’s famed obscurity; “decadent parlance” is quite another matter and is by no means a guaranteed source of opacity. While Mallarmé’s obscurity has become proverbial, “decadent parlance,” conversely, is seldom associated with him. Henri de Régnier himself lists several poets who employed “decadent parlance,” but he does not include Mallarmé.

Indeed, Mallarmé’s work lacks those “navrances” and “errances” that define the genre today; he even urged poets to “allies together the words, the perfect words, belonging to some school, dwelling, or marketplace.” In contrast, his later works are filled with what Camille Mauclair rightly termed verbal subtleties, meticulous constructions handled by a grammarian, linguist, and purist, full of complexities, and intricate interplay of syntax and punctuation. Especially in his prose, we find sentence dislocations explained by the intent to reflect thought’s natural motion, emphasise a nuance, or indulge in refined grammatical subtleties.

Consider, for example, the paragraph in Divagations (page 273), which leads to the famous line we quoted:

A proposition said to come from me—cited here and there, whether in praise or opposite—I claim it, fully, along with those others soon to gather here—states, simply enough, that everything in this world exists ultimately to find its way into a book.

Or this one, even more striking (page 263), and it’s the beginning of a chapter!

Not even that, then; it wasn’t to be: Naïvely, I’d just started to delight in it. Six months have slipped by, lost to forgetfulness; and here we are again, with our literary production abounding, blossoming, spreading, as ever.

Mallarmé will not always fall into these errors; to forget them, let us reread this intensely orchestrated beginning of the article on Hamlet (page 165):

Our fledgling self, who slipped away at life’s dawn, yet destined to haunt high or wondering souls, draped always in its mournful garb; I see it, straining to make its presence known.

Mallarmé exemplified, in its highest form, the definition of the great writer: no one captured more profound ideas with a richer resonance or greater musicality of voice. Open Divagations at any point—take, for instance, the sentences we’ll quote at the end of the next chapter—and you will witness this quality firsthand. But this remarkable writer, whose impact goes well beyond the extraordinary, spoke in a language entirely his own creation.

The fact that Mallarmé not only persisted in the “decadent style” but immersed himself further into it with age demonstrates that this was no mere passing trend. Rather, his grammatical forays and disjointed syntax grew out of his genius and aligned well with his core doctrine: to push past the limits of the real.

Did he ever, at some point, question this path? When he agreed, in 1886, having already published Prose pour des Esseintes, to become a regular contributor to the Revue Indépendante, he declared—let me bear formal witness to this—that he wished to reach a larger audience. What exactly did he mean? Was he responding to the critiques of obscurity that dogged his verse? The fractured syntax for which his prose was so often rebuked? It is plain enough that he never truly succeeded in reaching the general public, but what, exactly, was his ambition in making this claim?

He could only view the syntactical distortions that delighted him as the finest means of wielding “the words, the right words…”. Yet, nestled among the Vers de circonstance, one comes across (on page 140) this couplet:

I ache with a toothache

From being decadent!

As for the obscurity brought on by his refusal to use the word “comme,” we could never be certain just how fully he realised its consequences. Did he not, with a wry smile, reproach Teodor de Wyzewa, who had published a sort of explanatory dissection of his poems, for insinuating that he was an obscure poet?

To help illuminate the issue, let me share this anecdote. When he brought me his first article, that profound and delightful piece on Hamlet, he asked me (evidently placing great trust in the young editor I was) to point out, on the proofs, any passages I felt might be too complex for the readers to digest. But of the few instances I flagged with the naïveté of my twenty-five years, he steadfastly refused to accept that any posed a genuine difficulty.

.

THE DREAMED WORK

.

In a letter to Aubanel dated July 16, 1866—let’s not forget, he was only twenty-four—we read the following lines:

…This summer, I have worked harder than ever before, and I can say that I’ve worked for a lifetime. I have laid the foundations for a splendid undertaking. Within each of us lies a hidden secret; many die without ever uncovering it, and having died, it vanishes, just as they do. I, however, have passed through death and come back with the jewel-encrusted key to my innermost spiritual coffer. Now it’s my task to open it, untainted by any borrowed impression, allowing its mystery to spread beneath a sky of great beauty. I need twenty years for this, and so I’ll shut myself away, abandoning all public exposure save for the reading of friends. I am working on everything at once—or rather, I mean to say that everything in me is so harmoniously arranged that, as each sensation arises, it transforms and naturally finds its place within a certain book or poem. When a poem is fully ripe, it will fall away on its own. You see, I am merely following the natural law…

In response to Aubanel’s request for clarification, he wrote back on July 28:

I haven’t yet managed to find a moment to explain the cryptic speech in my last letter, and I dislike being a riddle to friends like you, though I do enjoy using this little trick to keep myself in others’ thoughts.

(It seems I forgot to shed some light?—light from the very lantern where I once hanged myself!)

What I meant was simply that I have just laid out the entire plan of my work, having at last found the key to myself—a keystone, or perhaps a central point, so as not to mire us in metaphors. A centre of myself, where I hold fast like a sacred spider, balanced on the main threads already spun from my mind, and with which I shall weave, at every point where they intersect, marvellous lacework, glimpsed in advance, and that already exists deep within Beauty itself.

…I foresee it will take me twenty years to complete the five books that will make up this Work, and until then, I will wait, reading only fragments to friends like you and scoffing at fame as nothing but a worn-out absurdity. After all, what is a relative immortality, so often cherished by fools, compared to the bliss of contemplating eternity and tasting it, alive, within oneself?

I’ll tell you all about this, and show you a few early drafts, if I can manage a trip to Avignon…

As Aubanel still found the lantern’s light dim, he wrote again on August 8:

“…For some time, I have been suffering intensely, in a way that must alarm those who care for me—and most of all, my Work, which I am now sketching out in full and which could be magnificent, if I live to see it through. I am speaking of ‘the sum of literary labours that shape the poetic life of a dreamer,’ what we ultimately call his Work. Are things clearer now, dear friend? How could you have missed my meaning before? I will describe the general outline to you soon enough, and then you will be enlightened…“

A letter I received from him some twenty years later attests that during that period—when we had only recently begun attending his famous Tuesday gatherings—the project was by no means abandoned.

Here is that letter:

Valvins, Thursday, September 10, 1885

My dear Dujardin,

I’ve delayed in responding simply because the languor of dear September casts its spell over all my afternoons. My mornings, however, are spent working intensely on tasks so jealous of my time that they even begrudge me a single sheet of writing paper. I’m drafting studies of the Drama, as I envision it, since the only way to convey something truly well is by showing it fully realised. This preliminary work is to become the gruelling task of my rare free moments this winter. You see, at this pivotal stage of my life (when I must finally shine), I am far removed from anything resembling collaboration—even from those tempting projects you mention. What I am attempting apart requires my utmost effort, alone, in solitude, while everything else feels irrelevant. I am thus less than ever a man of any Review, even yours! A single quatrain, for someone like me, beset by illness and obligations, flings me two weeks away from the rugged path I am climbing in thought. But we’ll speak again in early October, which is nearly upon us; and if I find the clarity needed to offer you some verses, they shall be yours…

The following year, in response to an article where I had done my best to describe the vision I thought I understood, he wrote again from Valvins on August 30, 1886:

…Through the goodwill of your friendship, you have set upon my ageing shoulders the magnificent burden of a destiny that perhaps I might have dreamed for another, if not myself…

Several of us were entrusted with similar confidences, and though Mallarmé often maintained a more reserved demeanour during our Tuesday meetings, it was never difficult to pick up on the cryptic references he made to the work he was preparing. This continued right up until his last days.

But what, exactly, was this work?

Had any of us dared to ask for specifics, he would surely have refused to provide them. Indeed, he had published neither a fragment, a sketch, nor a plan, and, aside from the rare exception I will mention shortly, nothing from it appeared after his death. To guide us, we were left with only the articles that have been later collected, notably in Divagations, along with his very conversations. As for the sonnets and short poems he occasionally wrote, he regarded them as mere exercises in style—what he called “calling cards” sent to journals seeking his contributions; mere interludes, in any case.

And what about the mystery behind those tiny “squares of paper” he wrote on? For thirteen years, wherever he went, we watched Mallarmé jotting down notes on small, pre-cut, uniform sheets of paper, which he never allowed anyone to read. One can only imagine the curiosity these little squared bits sparked in the young poets we were at the time! A story once circulated among us. One of us supposedly found himself alone with Mallarmé in his study, the bundle of paper squares within reach, and Mallarmé was speaking in detail about everything he had written on them… Just then, the doorbell rang. Mallarmé, going to answer it, left his young companion alone, who seized the opportunity to peek… It turned out to be nothing more than his pupils’ English homework. Mallarmé scolded me for having spread the story; I protested, though I believe Barrès was the true culprit.

At his request, these papers were disposed of following his death. It is highly likely that each contained a few words—often very brief—where Mallarmé captured the connections between things and ideas that formed the bedrock of his thought; many of these may well have found their way into his poetry and his articles. It is also exceedingly likely that none of these papers held an overarching vision, a grand blueprint for the work he had planned.

In the end, it is the recollection of his conversations that has enabled us to piece together the story of this work, guided by the articles compiled in Divagations as well as by the letters and documents published later, the most significant of which is the sketch entitled Igitur. Published twenty-five years after his death, this work is, in fact, the key that unlocks his entire oeuvre.

As I have mentioned, Mallarmé had ordered the destruction of his papers after his death, and it is known that his wife and daughter had the daunting courage to carry out this wish—at least partially. Indeed, they spared a few pages they deemed to form a coherent whole, setting them aside in secret, and, as far as I know, never confiding them to anyone in their circle. Among these pages was the manuscript titled Igitur, or La Folie d’Elbehnon (The Madness of Elbehnon), which Mallarmé’s son-in-law and heir, Dr. Bonniot, would eventually publish in 1923.

But what exactly was Igitur?

We had once come across an article published in Le Figaro on August 10, 1902, bearing the signature of Catulle Mendès, devoted to Mallarmé.

In this piece, Mendès began by recounting how he had first met Mallarmé, and then how, in 1870, just before the war, he had visited him in Avignon, accompanied by Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. There, Mallarmé had read them a kind of long prose poem—or rather, a highly abstract tale—that he had been working on for several years, a work Mendès called Igitur d’Elbehnon. Mendès went on to describe the profound unintelligibility of the piece, lamenting the desolate impression it had left him… Mallarmé, he said, had lost his way as a poet; he was a man adrift on the sea…

The article itself was tinged with bitterness; Mendès, as is well known, never forgave Mallarmé for the cult-like reverence he commanded among the younger generation. Published less than four years after Mallarmé’s death, the Figaro piece had little impact. It revealed that Mallarmé had spent the years leading up to the 1870 war working on a project he later abandoned, but beyond noting that the work was written in an almost impenetrable language, no further details were offered. It attracted little attention, especially as Mallarmé had stopped speaking of it in the years after. In fact, it was commonly believed that the manuscript had been lost, for Mallarmé’s papers were widely thought to have been destroyed, and no one knew that an exception had been made in this case.

The prose poem titled Igitur, written between 1867 and 1870 and later abandoned, stands as the first draft of the work Mallarmé would dream of throughout his life.

It is not only the first draft, but the only one we possess.

According to the account provided by Dr. Bonniot in the preface to his edition, Mallarmé initially considered embodying the “mental attitude of the Hero” within the myth of Herodias. Yet, after composing the fragmentary dialogue he would later publish, he abandoned this approach and “surrendered himself increasingly to the exploration of the self, within an ever more impersonal framework.” Thus, he conceived a being of his own making, sui generis, one unbound by any legend, and created Igitur, or La Folie d’Elbehnon, likely between 1867 and 1870.

In August 1870, Mendès and Villiers de l’Isle-Adam visited him, to whom he read this sketch.

Then, ten to twelve years passed, during which no word was heard of Igitur. It was only after that that we encounter the recollections of George Moore, recorded in his Avowals and later republished in an article in Le Figaro on October 13, 1923.

At a date Moore did not specify, though certainly before 1884, Mallarmé supposedly confided to him that he was working on a kind of drama. It would have contained but one character, influenced by Hamlet, the last of his kind, residing in an ancient castle where the wind howled, compelling the young man to venture across the world to restore his family’s fortunes. Yet, the young man remains unsure, torn between leaving or staying… “Considerable,” Moore notes, “was the role of the wind…”

These episodes do not appear in Igitur, but this young man remains none other than Igitur himself; it is clear that the drama Moore heard about had its origins in the prose tale-poem Mallarmé had previously shared with Mendès and Villiers de l’Isle-Adam.

From the end of 1884, my own recollections come into play. The work Mallarmé had in mind was still, as it was when he spoke to Moore, a drama. This is evidenced by a letter he wrote to me in September 1885, which I have just quoted. Moreover, he seemed intensely absorbed in ballet and the figure of the dancer, speaking of the dazzling visions that would later find their echo in Divagations. He also expressed his thoughts on the book, the ideal book… Is the work he imagined now a book? Has it ceased to be a drama?

Two months after that letter, in which he still envisioned the work as a drama, Mallarmé wrote to Verlaine on November 16, 1885, a lengthy note offering the autobiographical information Verlaine needed for the Les Hommes d’aujourd’hui issue dedicated to him. Here is what he shared:

Beyond the prose pieces and verses of my youth, and the rest, an echo of it—scattered across the first issues of various literary reviews—I have always dreamed and endeavoured, with the patience of an alchemist, to bring forth something greater. Prepared to sacrifice all vanity and personal satisfaction, as in ancient times one might burn their very furniture and roof beams to stoke the furnace of the Great Work. What was I striving for? Simply put, a book—yet not merely a book, but a true work of architecture and purpose, unfolding across multiple volumes. A book that would truly be a book, not just a collection of inspired fragments, however marvellous. I would go further still: the Book itself, convinced, in my heart, that only one Book truly exists—a work pursued unconsciously by all who write, even the Geniuses. The Orphic explanation of the Earth, which is the poet’s sole duty and the supreme literary game.

By the next summer, I felt justified in suggesting, in an article, that Mallarmé’s published works thus far were simply preparatory steps toward his “poem in twenty volumes.”

And this is what these lines by René Ghil were meant to clarify:

“The Work,” René Ghil writes, “as far as I understand, was to be composed of twenty volumes. Four of these would contain the core propositions, serving as the foundation for the entire series. They would be bound together to form the very centre of his thought, radiating outward. From each of these four central volumes, four additional volumes would unfold, each directly inspired by its source. In this way, the complete Work would take shape as a philosophy of the World.—In 1887, he shared with me the guiding Idea for only one of these thematic volumes, which was to develop this notion: ‘If I didn’t exist, nothing would exist.’ Beyond this, Mallarmé offered no further details on its structure or contents.”

So, nothing personal in this, then. We are led to believe that, had this Work ever reached its final form, it would have expressed, in its philosophical essence, an idealism centred on the Self as the embodiment of the World-Creating Idea—that would have called to mind everything from Plato through Fichte, Hegel, and Schelling.

…Further indications hint at the way Mallarmé planned to arrange these volumes: each was to be produced in duodecimo format, with the very folding of the paper playing a role in articulating the Work’s ideas. The book was intended to remain untouched, its pages uncut; the reader would first encounter only those pages visible along the outer edge of the volume. From this initial exploration, they would gather the ‘exoteric meaning’ of the Work. Only then, prepared by this first layer, could the reader slice through the untouched pages, revealing the complete, ‘esoteric meaning’.

René Ghil goes on to say that “the requirement of such folding to convey thought gave him the gravest doubts about the grandeur of the promised work.” Ghil was sorely mistaken—quite seriously so—in failing to see that Mallarmé’s paradoxical statements were often no more than an amused exaggeration of an original, profound idea. And Ghil was equally remiss in not recognising the playful spirit behind the analogies Mallarmé delighted in creating.

Consider, for instance, this vivid portrayal of a character Mallarmé had envisioned:

…hieratic, beardless, entirely enrobed in elaborately white fabrics, unmoving—on his head, a domed papal tiara, also white, encircled with three crowns studded with every jewel…

“A phallic symbolisation,” Ghil writes, “and syphilitic,” he might as well have added; yet Mallarmé’s own expressions were infinitely more direct! Ghil found it remarkable that Mallarmé could believe in such an elaborate display; I, however, am taken aback that Ghil missed the master’s own cues for laughter. The fine René Ghil simply lacked a sense of humour. And if I pause over these particulars, it is to emphasise that, contrary to what some might imagine, the pure and angelic Mallarmé was not at all devoid of humour. Far from a dour magister, his conversation, lofty as it often was, shifted constantly between the sublime and the familiar, with wit springing up at every turn.

What, one might wonder, was the connection between the book in which Mallarmé planned to enshrine his work and the poetic drama he had, on other occasions, discussed with his friends? René Ghil poses the question and admits that he could not find an answer. I hope to have better luck.

It is 1885—the year Mallarmé encounters Wagner’s work, as I have detailed earlier. This moment marks a crucial juncture in the evolution of his thought. In Wagner’s creations and theories, Mallarmé instantly recognises an embodiment of his own aspirations; for in place of being merely the entertainment of an evening, art transforms into a kind of religious ceremony where the audience is awakened to the deepest, truest part of itself. Yet the Wagnerian influence did not merely manifest in what it revealed to Mallarmé, but in the very reactions it provoked in him. Three elements, in particular, strike him as fundamental errors in Wagner’s philosophy and works: the anecdote, even when it ascends to the level of myth; the actor, whose impure personality seems, to Mallarmé, not to serve as a mediator between the audience and the poet, but as an impediment; and finally, the material set.

Mallarmé envisions an artwork devoid of action, unfolding its spiritual rite unimpeded, with no other décor than that which the figures of dance themselves establish.

The question of “music,” in its technical sense, does not hold him back. The “music” he dreams of will not be that of violins and brass, but of the language; we know well how he declared that “poetry must take back from music what is rightfully its own.” Let us read this remarkable passage:

Indeed, I never take my seat in the concert hall without sensing, within its obscure sublimity, the faint outline of one of the poems that are immanent to humanity in their most original state. It occurs to me, perhaps due to an unshakable writer’s bias, that nothing will remain without being proffered; that, at this very moment, we find ourselves searching for the transposition into the book of the symphony, in which we are meant to reclaim what is ours. For it is not through the elementary sonorities of brass, strings, and woodwinds, but through the intellectual word at its highest form, that there should result, with both fullness and clarity, Music as the totality of connexions existing in all things.

A drama stripped of anecdote, actors, or scenery; a solemn event where “the crowd unwittingly attends to the manifestation of its own grandeur,” as the music of verse reclaims its right from the orchestra—who would dare question such ideas? With Wagner, we found ourselves among the realisable and realised; here, we are taken into realms born of the mind alone. And yet, these mental visions rank among the most potent ever imagined. Could this, perhaps, have been the work Mallarmé dreamed of?

Here, a critical distinction needs to be drawn—one, I believe, that has not been sufficiently recognised—between what Mallarmé envisioned for the future and what he considered within his own reach. He himself sets this distinction from the very outset of his piece on Richard Wagner. And since the supreme artwork he imagines remains, for now, unattainable, he feels more free to delineate its vision. Yet this vision is not to be confused with the work he intends to accomplish himself. The divide between the two is immense, and I do not hesitate to express it as follows:

The sovereign artwork shall one day come alive on stage; his own work, he will bring into being in the form of a book.

After the Wagner essay in 1885, Mallarmé’s writings in the Revue Indépendante of 1886-87 (included in Divagations under Crayonné au théâtre, excluding the fourth and ninth pieces) broadened his theory of a sovereign artwork that he placed in contrast with Wagnerian art, yet barely addressed the subject of the book. It was only in his essays for the National Observer in 1892-93 (compiled in Divagations under Planches et Feuillets and further) and his 1894 lecture on Music and Letters that he began to juxtapose the book and the theatre directly.

The book, then, would serve as the transposition, in a few pages of verse, of the ideal theatre. Let us turn to some of these passages, chosen from many.

The sovereign work, he writes,

Never synthesises anything other than the timeless, innate delicacies and glories that are unbeknownst to all in the gathering of a silent audience.

Waiting for it to happen,

The book will try to suffice, to slightly open the inner stage and whisper echoes into it.

The pleasure the late Dreamer-King of Bavaria sought in vain—sitting alone as scenes unfolded—can actually be found not by dismissing the baroque crowd, but by stepping back from it, allowing the text, in all its bare essence, to become the spectacle. With just two pages of verse and the presence of my whole self, I can bring the entire world into being! Or at the very least, I quietly glimpse its unfolding drama.

Elsewhere again:

If a book in our hands expresses an august idea, it stands in for all theatres—not by making us forget them, but, quite the opposite, by imperiously reminding us of them.

Henri de Régnier spoke of what this work’s purpose should be:

To express man, not merely as a self-centred individual, but as someone connected to all things.

Man, as Mallarmé himself wrote, and his authentic stay on earth exchange a reciprocity of proofs.

It is this confrontation of man with the universe that lies in embryo in Igitur and of which Coup de dés is the dazzling synthesis.

Let us briefly recount this story of the imagined work.

At its inception, perhaps it was the myth of Herodias; but Mallarmé discarded it almost immediately.

The first outline: Igitur, which in 1870 he read to Mendès and Villiers de l’Isle-Adam.

Next came the Hamletian drama, the theme of which he recounted to George Moore.

Soon after, a philosophical expansion, most notably expressed through his theory of ballet.

In 1885, his encounter with the works and doctrines of Wagner led him to refine both his theory of the theatre as a religious festival and his concept of the book.

But this book—can we say it exists? Should we call it a chapter? An abridgement? A sketch? It is Coup de dés, which at the very least offers a glimpse of what Mallarmé’s intended work might have been and may, in fact, represent his first attempt at it.

The twenty volumes announced in 1887—could they, ten years later, have materialised as a small booklet of only a few pages?… “Two pages and their verses,” he was already writing in 1893!

It seems, then, that we can reasonably conclude that the work Mallarmé dreamed of is the one he began to sketch in Igitur, commented upon in his conversations and in many pages of Divagations, and partially realised in Coup de dés.

Was Coup de dés a conclusion? Or was it a beginning?

Mallarmé died at fifty-six, in full possession of himself, at the peak of his genius. Had he lived longer, would he have completed the work he envisioned?

Many men die having accomplished what they set out to do, but it seems this particular work was one of those conceived never to take shape.

This is one of 50+ rare French literary texts translated into English for the first time on this site.