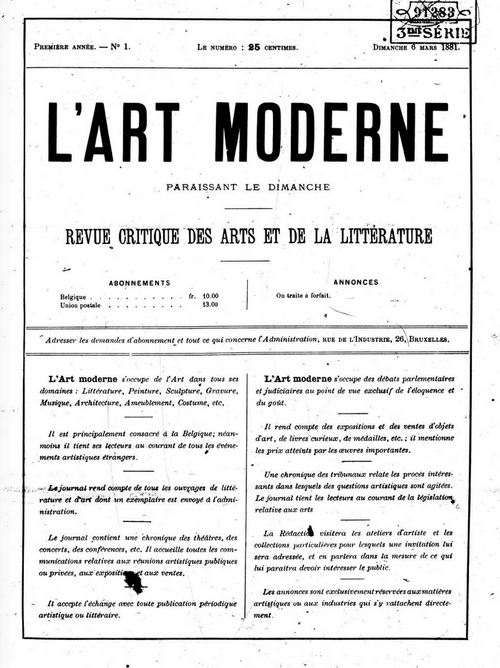

The following is the first-time English translation of “Quelques mots sur Mallarmé” by Émile Verhaeren, published in L’Art Moderne, No. 44, Sunday, October 30, 1887.

An ex libris by F. Rops graces the entrance to the photo-lithographs of Stéphane Mallarmé’s Manuscript, a limited edition of forty copies published by the Revue Indépendante. This Manuscript is a treasure trove containing all the master’s published poems, along with some that have never seen print.

The ex libris depicts a Muse seated in the clouds upon a chair whose backrest is a haloed question mark. She holds a lyre with strings extending into infinity. Two vibrant, living hands draw melodies from it, whilst skeletal fingers flutter about in futile attempts to reach them. At the base, a chaotic pile of laureate and academic skulls serves as her footrest, and at the very bottom, a spectral poet rides a macabre Pegasus, charging headlong towards the stars.

The drawing’s meaning is clear enough: it symbolises the elusive nature of supreme art and the vertiginous difficulty of attaining it. The execution is nothing short of superb.

When read for the first time in its entirety, the work asserts itself with its symphony of metal and stone, its cunning enchantments, and its philosophical and artistic logic. It is structured like an ancient temple of golden opulence, where mysterious marbles, clear in their lines, initiate serene mysteries. The architecture is both simple and complex—columns veiled in obscure light, with brilliant diamond embroidery. Closed tabernacles, whose keys are scattered within a sonnet. The essence of things is always there, presented to us as if mounted in a monstrance, with the most intimate part, the host, always at its heart. Mallarmé’s art first dazzles, then reveals itself, and finally commands endless admiration.

Among true poets, no one dares deny this any longer. They even use his name to rebuke those climbing the ladder, crying: “Mallarmé! Yes, that’s all very well, but what about the rest of us!”

He is indeed little understood, which is fortunate as it saves him from the sacrilege of excerpts and scholarly quotations.

We cannot praise highly enough his marvellous expression, always so apt and unique in conveying the essence of his sensations. His words express more than anything else and fully convey colour, sound, taste. And his playfulness and skill are prodigious! Here, the alexandrines are forged into harmonious chords, robust as pedestals, orchestrated like majestic columns. They often rise, tall and slender as resplendent towers, or lie dormant, shimmering with the tranquil luminescence of serene lakes and reflecting mirrors. Each line is meticulously sculpted, like a piece of fine furniture, adorned with the intricate inlays of lacquer and enamel. There, the octosyllabic sonnets, ethereal as gossamer, conjure the whispers of a gown trailing in dance, the soft rustle of a fan unfurling, the melodious sigh of a bloom in song, the gentle clink of a descending pearl, and the soothing hum of a viola resonating with its final note. Mallarmé’s touch is prodigious in its suppleness, brushwork, and intensity. O Wagner!

In his poems, each verse doesn’t necessarily carry complete and independent meaning, and the whole isn’t merely a juxtaposition of fragments and details. What strikes one is the luminous and logical totality. His sonnets don’t merely enlighten; they explode before the mind—dazzling, chiselled blocks. They often lack direct sense; they are sometimes a dreamy and symbolic evocation, a grand image giving rise to lofty thought. This is the case with these two sonnets: “To insert myself in your story” and “Does Pride at evening always fume”. At other times, they present an epic or statuesque vision, as in “Homage to Poe”. Or they offer a psychology of existence, a moral lesson, as in “The Chastised Jester”. Finally, they paint sentimental truth, as in “What silk steeped in the balms of time”.

What always asserts itself is hauteur and, if I may, the lessons gleaned from the poem. Mallarmé’s genius is fundamentally philosophical, nourished by robust marrow and built upon speculation and transcendence. In the current edition of his works, he has made corrections to opening stanzas here and there, solely, we believe, to unify the fundamental beliefs expressed throughout. The term “God” is omitted and replaced either by an appeal to Nature or a poetic prayer. In such verses, it is the Self that takes its place. Hence order prevails, along with reason—a reason that is philosophical, aesthetic, and mathematical all at once. The result is clear unity everywhere, as well as method, which is why Mallarmé is the greatest classical genius we still possess in France.

However surprising this claim may be, we believe it true—and neither the technique, nor the construction, nor the linguistics of his verse will contradict us. He, more than anyone, has tempered his language at its roots and writes more logically than anyone else. His words stand firm and lucid, and when intimately embraced, they always seem perfectly chosen. They exist independently, like the cells of a living organism, each pulsating with its own life. Yet when woven into poems or fused into the unity of stanzas, they thrive in social symphony, each word lending its voice to the harmonious chorus of the verse. They also express a sudden, unexpected, luxurious vitality which only a magician’s fingers can bestow. They vibrate with electric and secret creation. Their tone is rare and splendid; their sound—a mixture of stones, metals, and light. Hence a serene, strong, daring, sometimes strange, but always penetrating poetics. Not melodic, but harmonic, broad, designed to express universal beauty and greatness.

The following is one of the unpublished sonnets from the new collection:

THE CHASTISED JESTER

Eyes, lakes with my simple rapture of rebirth,

Other than the actor who with gesture summoned

Like feather the ignoble soot of oil-lamps,

I pierced a window in the canvas wall.

Of my leg and arms a limpid, treacherous swimmer

At multiplied shores, renouncing the bad

Hamlet! it's as if in the wave I fashioned

A thousand sepulchres to disappear there virgin.

Hilarious gold of cymbal struck by angry fists,

Suddenly the sun strikes the nakedness

That pure exhaled from my nacre freshness

Rancid night of skin, when over me you passed

Not knowing, ingrate! that it was all my anointing

This greasepaint drowned in the perfidious water of

mirrors.

.

This sonnet, where so much crystal and filth are juxtaposed in fitting words and which is characterised by that marvellous “I fashioned in the wave a thousand tombs” and by that wild cry “Hilarious gold of the cymbal” and by that discovery “Rancid night of the skin”, appears in the first booklet.

The entire edition is successful, original, meticulous, worthy of the foremost poet of France today, whom it presents to the refined and the delicate.

We plan to delve deeper into a study of the Master soon(1).

____________________

(1) For detailed scholarly analysis of “Le Pitre châtié,” consult the following studies:

Articles:

- McLendon, Will L. “A New Reading of Mallarmé’s Pitre Châtié.” Symposium: A Quarterly Journal in Modern Literatures 24, no. 1 (1970): 36-43.

- Newton, Joy, and Ann Prescott. “Mallarmé’s Clown: A Study of Le Pitre châtié.” Kentucky Romance Quarterly 30, no. 4 (1983): 435-440.

- Anderson, Jill. “Verse in Crisis. Towards a Poetics of Self-Estrangement: Mallarmé’s ‘Le Pitre châtié’.” Australian Journal of French Studies 31, no. 1 (1994): 15-28.

Book Chapters:

- Austin, Lloyd. “Mallarmé’s Reshaping of ‘Le Pitre châtié’.” In Poetic Principles and Practice, 155-169. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Cohn, Robert Greer. Toward the Poems of Mallarmé, 37-42. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1965.

- Fowlie, Wallace. Mallarmé, 90-96. 1st Phoenix ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

This is one of 50+ rare French literary texts translated into English for the first time on this site.