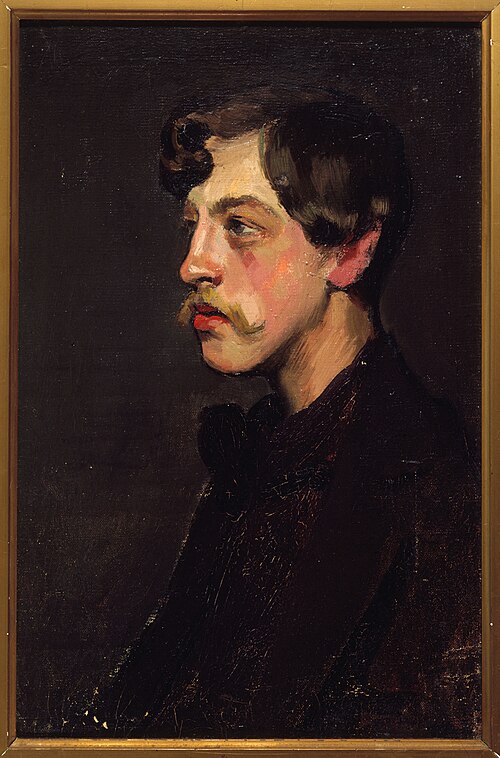

Camille Mauclair by Henry Bataille, c. 1895

The essay that follows is translated here for the first time from Camille Mauclair’s Princes de l’esprit, published by Albin Michel, Éditeur (Nouvelle édition).

MALLARMÉ’S QUEST

"We knew none of these things until after his death." Life of Pascal, by Mme PÉRIER

I wrote these pages about my master twenty-three years ago, in the first anguish of his death. I present them unchanged. Time alone will test their worth, and though I know their imperfections, their sincerity endures—a witness that the years have only strengthened.

Here was a poet wrapped in mystery, yet surely one whose name rang through the literary—and pseudo-literary—press of Europe more than any other. Few seekers after truth have drawn such volleys of mockery and dispute. Mallarmé, supremely indifferent to it all, attracted the most singular judgements. Everything about his work pointed to perpetual neglect by public and press alike; yet periodically, a kind of exasperated deference would seize the gazette-writers and those ordinarily deaf to unconventional literature, who felt duty-bound either to rage or to demand, with nervous irony, that someone “explain M. Mallarmé”. Nothing could appease them. Stéphane Mallarmé eluded all categories; what’s more, he wished to elude them—to stand alone. He sought neither comprehension nor converts; he desired only his solitude and the freedom to shape language to his own vision. This stance, simple though it seems, nearly always draws more attention than its practitioner desires. The clamour surrounding Stéphane Mallarmé was pure cacophony. Every insult known to letters, I believe, found its way to him. Even in his final months, anonymous letters arrived from souls so maddened by incomprehension that they threatened him with every conceivable outrage. Not a schoolboy scribbler, not a music-hall rhymester or gossip-monger or penny-a-line hack failed to sound his note in the chorus of mockery, each eager to school the author of L’Après-midi d’un faune in proper French. They painted him as lunatic, egomaniac, charlatan, false prophet, oracle-monger—a Sâr Péladan stripped of the outlandish costume. Like Socrates before him, he stood accused of corrupting youth; his intimate Tuesday-evening gatherings barely escaped suspicion of conspiracy. Critics dissected his perversity, his Byzantine obscurity, the perils of his nebulous doctrine; only the charge of immorality failed to join these scandalised complaints. To the licensed critics of the right-thinking press, Stéphane Mallarmé was the monstrum horrendum.

And yet they couldn’t quite dismiss him. They sensed they faced “someone”. Silent conviction, daily labour, and sovereign contempt for worldly opinion and advantage must wield magnetic power, for while Mallarmé’s name provoked howls of derision, it commanded peculiar authority. Unable to comprehend, his detractors laced their barbs with involuntary respect. To face the incomprehensible brings humiliation, self-doubt, and despite everything, obscure reverence for the creator—as peasants watch a painter work, scorning yet respecting his mysterious sketches. The cruellest wits would have given much to boast they understood him, and would have prized themselves the higher for it. Time silenced most; an indifferent will, through mere persistence in silence, had conquered. Yet the fact remains: for twenty years of his life, Stéphane Mallarmé was pilloried. Anyone judging by the public prints could conclude only madness, perversion, imposture, diseased imagination, and fraud.

Such was the portrait drawn of Stéphane Mallarmé. The man himself bore no resemblance to it. This “madman” possessed a mind of crystalline logic, a philosophical intelligence of rare power whose only defects were excesses of rational rigour. This “egomaniac” lived simply, withdrawn to modest quarters whose only luxury was personal taste and a few modern canvases, poor throughout his days, calling on no one, contributing gratis to young poets’ journals. This “impostor” was sincerity itself, a driven worker possessed by perfection, devoted to his mother tongue with religious fervour, consecrated utterly to literature—his only passion, joy, and reason for being, yet also his martyrdom (the word is exact, and if it fitted Flaubert, it suits Mallarmé still better). This “sibylline oracle” was personally the soul of courtesy, touched with the finest grace of French civility, whose charm, melodious voice, and warmth enchanted all who met him. Here the testimony is unanimous. Two generations of artists remember Mallarmé as an incomparable conversationalist whose dreaming, luminous discourse we shall not hear again. Many who had scorned his work, even savaged it, found themselves in his presence conquered and transformed, departing with regret for their attacks. They say Mallarmé professed symbolist doctrine, warping young minds with his teaching. Pure fiction: the poet stood always as an individualist, writing by methods suited solely to his own inspiration, refusing the teacher’s role, urging each to trust themselves alone. If young men lost their way through listening, they surely lacked originality and misconstrued pronouncements meant only for their maker; if Mallarmé influenced anyone, it was through force of character, disinterestedness, quiet personal elegance, and nobility of spirit. Nothing here to corrupt or found a school. As for Mallarmé’s actual forms, no one else has ever employed them. Perhaps two or three verbal tricks—a way of setting epithets between commas, a fleeting use of infinitives as present participles for special effect—have passed from his pages to those of certain friends. Nothing more—which is to say, almost nothing. The truth is this: as man, as aesthete, in taste and “poetic colour”, in metaphysics and in all things of flesh and spirit, Stéphane Mallarmé stood inimitable, without peer in his age, a being whose mystery sprang above all from this utter unlikeness to any other, who defied pastiche, who formed a coherent, ordered, logical whole pushed to ascetic extremes, driven by iron will beneath gentle manners. When Rodin, returning from the cemetery, asked, “How long before nature makes another such mind?”, he caught precisely what all Mallarmé’s intimates felt—the sense of encountering the exceptional. Disinterestedness, systematic rigour, stylistic purity, taste, order, personal dignity—all in him was absolute, unwavering, governed always by duty once embraced.

Why then this chasm between the man and his reputation? Why was such individual distinction so misread? After all the articles and critical forays, the controversies, gibes and homages, why has our age still not grasped what Mallarmé was? Twenty-five years he laboured, daily, with fierce intensity; he harvested mainly abuse, offset by youth’s respect after 1884 and admiration from distinguished foreign minds. Most notable writers from England or Central Europe passing through Paris paid reverent calls on the maligned author of Hérodiade. To them, he ranked among the French masters. But they knew him better than Parisian journalists. Truth be told, if the attacks were mostly wrong-headed and ill-informed, half the praise lavished on Mallarmé is worth no more. The poet cared for neither. He lived always apart, receiving many visitors but few friends. His private existence remained closely guarded. Édouard Manet, Madame Manet (Berthe Morisot), Théodore de Banville, Degas, Monet, Whistler, Odilon Redon, Rodin, Renoir—these were his true intimates, along with some of today’s younger poets and musicians. Fame touched him like calumny, altering nothing. Yet while he made no display of his life and person, neither did he conceal them. They lay open to study. Above all, one might have noticed before mocking that such sustained effort over so many years, crowning early works all acknowledged as beautiful, could hardly produce either hoax or madness, but rather some deeply pondered conviction deserving patient scrutiny. But experience proves too well that such credit is rarely extended to minds that leave the beaten track. Now that we speak of the dead, we must undertake a thorough reappraisal; the mystery that lent the man his charm must not obscure his work. It should face the full light of day—it will not flinch. We must discover why such discord arose between Stéphane Mallarmé and his reputation; what he sought to achieve, what he wrote, what aesthetic he conceived—all this demands clear and balanced examination.

* * *

The career of Stéphane Mallarmé is familiar enough; it offers scant matter for curiosity, being wholly interior. The lives of men devoted to Meditation, those “given to dreaming”, as he styled himself, turn entirely inward. Their events are of the spirit, their upheavals and adventures abstract. Mallarmé first appeared to the friends of Leconte de Lisle—to Coppée, J.-M. de Heredia and the rest—within the Parnassian circle towards the Empire’s close. He presented a discreet, concentrated personality that his comrades immediately marked for observation, they being far less given to reverie, more taken with cold beauty and a sculptural verse that banished all musicality. Mallarmé drew directly from Baudelaire’s dark and achingly lyrical thought; beyond this, he was an ardent Wagnerian, devoted to symphonic art, and the most passionate advocate of Manet’s painting and those early ventures into impressionism that the creator of Olympia was pursuing with his friend Claude Monet. These leanings swiftly set Mallarmé apart from the Parnasse, alongside Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, who shared at least his Wagnerism and taste for the mysteriously lyrical. Léon Dierx too—sentimental and musical, of muted tones and grave lyricism—stood distinct from the brilliant, hollow Parnassians. A parting of ways was inevitable. Villiers de l’Isle-Adam turned to occultism and the idealist novel, bestowing upon French letters L’Ève future and Axel. Léon Dierx had merely to remain the solitary soul he had always been. Stéphane Mallarmé was forging a logical and philosophical method too rigorous not to break away more decisively still. When he applied his artistic theories in a poem, L’Après-midi d’un Faune, his Parnassian comrades raised an outcry and, as he remarked with a smile, “the piece was rejected with splendid unanimity”. From that day forth, Mallarmé withdrew, maintaining personal relations with his colleagues that never failed to honour his exquisite character. To Théodore de Banville he remained, to the very end, a friend amongst friends, one whom that great charmer valued with matching nobility through every turn of fortune. Mendès, Coppée, Heredia, Leconte de Lisle all found themselves accompanied from the depths of his retreat by their excluded comrade’s unwavering smile and steadfast loyalty. But henceforth he worked alone, pursuing against public opinion, poverty and obscurity the inexorable development of his convictions.

His life, sustained meagrely by his salary as a teacher of English at various colleges—the pension for which came only some four years before his death—unfolded without notable incident.

In the concert halls one might glimpse a slight man with magnificently dreaming eyes, a head held proud and calm, a bearing of unaffected distinction. One knew he laboured in silence and published almost nothing. Several poems of magisterial elevation and form had preceded L’Après-midi d’un Faune; amongst the refined, Les Fleurs, l’Apparition, l’Azur, le Guignon, les Fenêtres were passed from lip to lip, along with those prose pieces titled le Phénomène futur, la Pipe, Plainte d’automne, and all awaited what might emerge from this great poet’s self-imposed exile. His translation of Edgar Poe’s Poems was deemed a masterwork, worthily completing for a definitive edition the magnificent rendering Baudelaire had made of the inspired American’s tales. To these must be added a preface to William Beckford’s Vathek and the edition of L’Après-midi d’un Faune with illustrations by Édouard Manet. Yet save for these testimonies, Mallarmé’s work remained invisible. His poems appeared in a sumptuous hand-copied album with a frontispiece by Félicien Rops, prohibitively priced and sparingly printed. Like Verlaine—another escapee from the Parnasse, drawn by his ill-starred existence down quite different roads—Mallarmé remained either reviled or unknown. Only in 1884 did the generation of young men soon to be christened decadents, then symbolists, seek out the solitary worker in his retreat and acclaim him master. Stéphane Mallarmé neither barred his door nor withheld from these new poets the fruits of his meditations on art. Thus were born those Tuesday gatherings that became legendary, and about which such absurdities have been written. The outcast found himself at the head of a school. Even as critical verve awakened, glory began to dawn.

Thenceforth Stéphane Mallarmé, publishing solely in the young men’s reviews without payment, bound to no newspaper, earning nothing by his pen, shared in his new friends’ varying fortunes, as he had shared those of the impressionists. Throughout his life this peaceable, earnest, gentle man—foe to publicity and fanfare, ever shielding his person from polemic and display—found himself amongst the maligned and bore their abuse atop his own. During those years from 1884 to 1898 appeared the Pages, encompassing the Notes sur la danse, the Rêverie sur Richard Wagner, the theatrical impressions first given to the Revue indépendante, and his theory of verse considered as a resource for musical expression. At intervals came poems and sonnets, which Mallarmé invariably presented as specimens of his linguistic experiments, where ideas counted for little, serving merely as pretexts for explorations in syntax and style: the lecture on Villiers de l’Isle-Adam; those on Music and Letters; sundry articles on poetry, concerts, Loïe Fuller, the poet’s moral being. The whole compressed into two modest volumes, one entitled Vers et prose, the other Divagations. Stéphane Mallarmé worked with ever-mounting deliberation and scruple: this slender œuvre cost him a prodigious accumulation of notes, which his last wishes expressly forbade to publish, and amongst which were to be found—if I may trust the memory of a private conversation—the conclusion of the poem Hérodiade and a drama. In his final years, Mallarmé had embraced a particular conception of free verse, having long resisted it. He had bent his researches to this end and had even published a characteristic example, of which I doubt criticism has taken notice. Mallarmé received his friends on Tuesday evenings, attended Lamoureux’s Sunday matinées without fail; since arranging his retirement, he lived six or seven months of the year at Valvins, near Fontainebleau, by the Seine, where he took to the water with passionate devotion. A simple life, so smooth, so peacefully consecrated to intimacy and labour, that a nervous spasm of the throat brutally ended it on 9 September 1897. The season meant that only intimates followed a funeral as discreet and dignified as the departed himself.

Such is all the chronicler can relate of this solitary figure. As for the very essence of his doctrine and writings, I shall endeavour to offer the reader commentary and exposition rather than “explanation”. Stéphane Mallarmé was an author of forbidding approach. To be obscure is not a defect but a particular understanding of the art or mental labour one pursues: Jacob Böhme and Swedenborg are decidedly obscure, as are certain mathematicians and certain theologians too, who nevertheless command considerable reputation and worth in the world. Two conditions suffice to justify such obscurity: to furnish reasons for it, and to reckon only upon readers and admirers proportionate to the hermeticism of what one presents to them. Some things resist exposition because they are inherently difficult; and obscurity is neither disorder, nor illogic, nor nonsense. To articulate something inherently obscure in its fitting form courts obscurity. Mallarmé’s demanding writings are not obscure in their explanation of their subjects, for that explanation remains always logical and ordered; rather, he addresses aesthetic problems few are equipped to discuss. The reader must choose: close the book or pursue enlightenment.

From the body of ideas Mallarmé set forth in his various writings and conversation, there emerges a comprehensive vision of literary and poetic art. I speak of his conversation, for Stéphane Mallarmé’s marvellous conversations were never recorded by his friends, and we must count this a grievous loss. Perhaps I shall raise a smile when I say here, drawing upon my memories as an intimate, that often his friends and I, following some luminous discourse inspired by genius, lamented our failure to emulate Socrates’ disciples in preserving their master’s words. Mallarmé repeatedly gave us that lofty sense of Socrates’ soul, whilst Verlaine conjured for us his face.

Yet the modern interviewer has rendered it impossible to stand, pencil and notebook at the ready, before a man articulating his thoughts: we should have appeared mere reporters or schoolboys taking notes. Mallarmé’s conversations, which would have formed an incomparable volume, embodied his entire dream and articulated his every aspiration for art. For this man who, the moment he took up his pen, was racked with scruples and weighed each word a thousandfold, became in speech the most unfettered, enthusiastic and copious of conversationalists.

Stéphane Mallarmé’s fundamental conception derives from Hegel’s metaphysical aesthetics, and one might say he was the systematic herald of Hegelianism in French letters. The absolute idealism of Hegel, Fichte and Schelling had already attracted Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, whose Claire Lenoir offers a curious application of the system; Mallarmé made it the very foundation of his labours. For him, pure ideas alone constituted the genuine and actual beings of the universe, whilst objects and all material forms were but their signs. “Somewhere there must exist primordial figures of which bodies are merely images,” writes Flaubert. This formula virtually embodies Hegelianism itself. The world’s appearances are but successions of signs, perpetually destroyed and renewed, of a constellation of ideas that alone are immortal and indestructible by virtue of their very abstraction, and that consequently represent the sole realities deserving the name. These transient signs we call symbols: each object is the fleeting symbol of its parent-idea. The world is but a system of symbols subordinate to a system of pure ideas governed by cosmic laws, whose synthesis constitutes the divine. Each symbol thus manifests and incarnates central reason. The universe becomes, as it were, a vast scripture wherein each object forms a letter, and whose totality speaks the divine: so that as thinking beings grow conscious of this symbolic writing through science, art and religion, they progressively decipher divinity itself and bring it into being.

It follows that artistic expression must employ realities to convey pure ideas, using them solely as intermediaries between human consciousness and God. Realism—the study of symbols for their own sake—becomes a futile pursuit, blind to art’s supreme calling. No art exists without material elements enabling thought to commune with fellow beings; yet the employment of symbols must constantly refer to an essential idea for which they merely serve as vehicle. Symbolic art must therefore eschew realities as descriptive ends in themselves, just as religion regards hosts, crosses or statues as but momentary tokens of eternal ideas, or as science examines organisms only in relation to the abiding laws that govern them. Art, religion and science share a common root in seeking God through ever-evolving forms. As we study symbols and discover beneath shifting appearances the abstract principles that constitute them, we shape a clearer conception of divinity; our consciousness reflects it more immediately, and the ideal becomes that through complete knowledge of the laws concealed beneath symbols, consciousness and the God it apprehends achieve unity. Every act of cerebral labour thus becomes, from this perspective, an act of religious faith.

This theory renders art a mystical manifestation. One consequence of Hegelianism is the wedding of aesthetics to religion. The study of forms from beauty’s vantage point becomes, according to Fichte, the study of God’s visible forms. Line and colour are abstract elements imposed upon matter yet distinct from it, being immaterial. They trace the divine within the world. Poet and artist thus become, in their fashion, priests.

They teach humanity to perceive God beneath the symbols. Emerson holds the same view. Confining ourselves to poetry, this theory accords with its very origins, which were sacred. The genesis of poetic language belongs to priests who intoned prayers and oracles in rhythmic, chanted speech, or with instrumental accompaniment; sibyls delivered their prophecies in lines bounded by breath more or less laboured, with recurring analogous sounds; scansion and the use of strophes have ever served to signal the utterance of weighty matters, particularly liturgical ones. Poetry is thus a chant expressing through music and symbols a religious idea. Lyric poetry alone merits the name; all other poetry—narrative, descriptive or rhetorical—deviates from prose, the language suited to reality’s direct expression. Poetry reconciles plastic and symphonic art through its command of epithets and verbal sonorities; yet it must seek neither to evoke the impressions proper to painting and sculpture nor to become mere sonic play. It must transpose these two arts and render their essence whilst remaining a sacred language, the language of the individual’s pure thought. Absolute idealism and individualism are the Hegelian system’s principles in metaphysics, art and ethics alike. The work of art thus stands inseparable from religious or philosophical work. The poet differs from the writer, who may skilfully express social notions or contemporary realities. The poet bears a singular mission. “He is,” declares Shelley, “the unacknowledged legislator of the world.” Poetry stands apart from literature proper, and poets form within society a contemplative order, like Dominicans or Carthusians. They are secular mystics charged with extracting from sentiments, passions, dreams—humanity’s lyrical yearnings toward divinity—their ephemeral elements, and expressing their eternal laws through symbolic imagery. Their language too must differ from that of ordinary mortals engaged in common discourse; it must be a refined tongue, selected from everyday speech and subject to special laws, following all sacred dialects drawn from each land’s vernacular.

These elements must combine in an archetypal work of art uniting every mode of expression: dance, mime, dialogue, painting, sculpture, symphony and verse. This vision haunted Wagner and governs the Ring. Such a work demands the crowd’s participation: it becomes the mass of aesthetics. The lyric theatre forms a church of the intellect, a sanctuary equal to any edifice devoted to worship. The book is theatre reduced: poem and prose may there epitomise dance, music, painting and pantomime, requiring no public presence. One may stand alone before a book and create a work of art and faith in reading’s silence.

Mallarmé, convinced of these principles’ validity, pursued them to their uttermost conclusions. His work is arguably unique in this regard: French letters offer no other instance of such systematic fusion of literary art with symbolic metaphysics. Having voiced in his early poems sentiments of noble pessimism and feverish beauty, Mallarmé gradually yielded to more serene, loftier considerations of greater elevation and scope, conceiving by degrees the design of a monumental work. Yet the more his lucid, determined mind grasped this work’s philosophical foundations, the more he recognised it demanded wholesale reform, the complete recasting of expressive means. The purist, perfectionist and theorist within him grew ever more exacting and painstaking. The work remained in draft; at every turn its preparation posed fresh problems, demanded new solutions, and Mallarmé died before he could marshal and distil his labours’ fruits. Still, if we possess but a handful of poems sufficient to proclaim an admirable lyricist, he had time to establish one of the most original, powerful and cerebral aesthetics ever conceived in France. He stands as its final representative, and amongst its most subtly compelling. Here then are the perspectives on artistic form at which he arrived.

*

* *

I have invoked the term literary martyrdom, adding that it was by no means excessive. For Stéphane Mallarmé truly felt his imagination—so expansive and beautiful—his passion—feverish and exalted—his lyricism—which suffused his least utterance and his whole being—all throttled by one eternal question: the perfection of form, or rather, the quest for an original form. “This linguistic labour through which, daily, my poetic faculty sobs at its own interruption,” he laments somewhere. Indeed, throughout his life he bore this burden: prisoner of his own scruples, he logically refused himself the right to build works before establishing them on renewed aesthetic foundations and methods. He fought against his creative urge: though an inexhaustible maker of images, as his conversation revealed, he denied himself the joy of expressing his thoughts until he had found the perfect arrangement of his expressive means. One can imagine the exquisite torture such a resolution breeds. Much has been made of the disease of perfection that afflicted Flaubert. Yet Flaubert at least could make sufficient peace with himself to publish works showcasing the fruits of his labour. Mallarmé enjoyed no such consolation. So mystical and absolute was his conception of art that he could never bring himself to offer any testimony he might pronounce satisfactory. One cannot fathom the depth of Mallarmé’s ardent, religious, almost fearful worship of literary art; this devotion lent his person something august, so palpable was his spirit of sacrifice and absolute dedication to poetry’s mysteries. “How often,” he once confided to me, “have I resolved to write the books I carried in my mind, contenting myself with conventional French forms, with eloquent approximations, with commonplace rhythms and syntax, swearing to throw off the yoke; yet at the moment of beginning, I felt I could not, that one has no right to abuse written language so—and I would return to studying its demands.” He studied to his dying day.

Mallarmé’s fundamental conviction regarding stylistic form was that written language stands absolutely apart from spoken language, and that the two have been wrongly conflated for centuries. By “spoken language” he included written phrases serving no abstract purpose but merely facilitating social exchange. All this he termed conversation. He refused to accept that the same language should serve lawyer, doctor, merchant and poet alike. The error stemmed, he argued, from the fact that whilst other arts possess their proper techniques and instruments—brushes, chisels, musical notation—literature appears to have none, borrowing instead from everyday speech. Yet this is precisely the pernicious illusion that breeds such lamentable misunderstanding. Laypeople who respect the brush, the chisel, or musical notation—whose use they cannot fathom—believe themselves equipped to judge a book straightaway without preliminary study, simply because it employs the words they use. So it seems: but in truth, a book earns its name only when the author has drawn from common language personal instruments as specialised as chisel or palette—in short, a style. Since words remain constant, style emerges through their arrangement. The arrangement of words is syntax. This science of fixed rules nonetheless varies infinitely, like alphabetic or numerical combinations, which know no limits. An original style may be forged in two ways: through the selection of epithets, and through varied combinations and cadences of the phrase. The choice of epithets yields what we call a style’s colour: the simplest degree of originality. It may venture far into rarity, singularity or seduction without necessarily marking a great writer. Varied phrase cadences create rhythm—style’s living element: the second degree of originality. Whoever demonstrates this must be a born writer. As for originality arising from syntax itself—from the construction and interrelation of grammatical elements—this is the most difficult and subtle achievement. The Goncourts or Pierre Loti exemplify colour; Flaubert, who invented two or three novel positions for the attribute, and Renan, who possessed the secret of presenting subordinate clauses with perpetual freshness, stand as exemplary prose masters, syntactic innovators who thereby erected imperishable monuments in French. Those who would dismiss such matters as secondary deceive themselves: the two grammatical discoveries concerning attribute and subordinate clause will secure the glory of Flaubert and Renan as surely as Salammbô and the Prière sur l’Acropole, rendering them classic. Syntactic innovation is exceedingly rare: it distinguishes a writer utterly. Mallarmé’s conception of style, then, was to pursue originality less through rare epithets than through varied cadences and, above all, through the reciprocal arrangement of verb, subject and complement. From this perspective, his research programme demanded rigorous study of punctuation.

Moreover, an entire realm lies open to stylist and linguist alike, in prose as in verse: musicality, which combines rhythm or movement of epithets—meaning that word placement should answer above all to the harmony of their particular sounds, employing the collision or fusion of these sonorities to serve the phrase’s overall cadence and thereby express its gracious, languishing, sombre or swift sentiment. If lyric poetry is song, so too is prose, for words signify equally through sound and sense—intimately linked, as we know from language’s origins—acting simultaneously upon the listener’s mind and senses. (We may consider the reader a listener, for he hears inwardly whilst reading, pronouncing to himself what he reads.) In daily life, people value meaning over tonality. The primary condition for a literary language extracted from common speech is therefore to honour greatly the sound of words, then euphony, then syntax. A writer’s personal stamp in the grand style corresponds to his discoveries along these lines.

“My era’s undeniable desire is to separate, as if for different purposes, the double state of speech, crude or immediate here, essential there. Narrating, teaching, even describing—these suffice, and perhaps for each person it would suffice, to exchange human thought, to take or place silently in another’s hand a coin; the elementary employment of discourse serves that universal reportage in which, save literature, all contemporary written genres participate… Speech bears upon the reality of things only commercially: in literature, one is content to allude to them or to extract their quality for incorporation into some idea.” These formulations perfectly encapsulate Mallarmé’s aesthetic and metaphysical position. They articulate clearly his conception of an absolutely specialised literary language and its necessity. He regarded contemporary novels as mere “reportage.” “All I have done,” declared Villiers de l’Isle-Adam on his deathbed, “amounts to French exercises”—the same preoccupation differently expressed, springing from a mystical conception of book and style. The phrase cited above—”Speech bears upon reality…”—summarises the transitions in Mallarmé’s mind between writing and symbolism.

This special language, withdrawn from common use through rare terms, multiplied cadences, vocal tonalities and peculiar syntactic usage, Mallarmé deemed fit for expressing not symbols themselves—for, as he notes, speech bears upon reality (or symbol) only commercially, that is, for ordinary social purposes—but rather for expressing allusions to symbols, extracting their quality for embodiment in ideas. Hegel himself could not have stated his doctrine more precisely. This method of allusion, fiction, allegory struck Mallarmé as the sole logical approach. Everything, to his mind, could only be allegorical, representative of truth. Following Edgar Poe, he banished from literary art proper and from poetry’s essence the genres of narration, description and eloquence, which he deemed alien to letters. A legendary art presenting fictional personages and ideological entities was the inevitable consequence of his style. Supporting this conviction was a personal gift he possessed to an astounding degree: the faculty of analogy. Stéphane Mallarmé’s analogical sense was developed to the point of astonishing anyone who conversed with him. Between the most disparate objects or actions, he discerned with unerring eye their point of contact and comparison. So naturally and powerfully did he conceive the universe’s infinite plenitude that nothing appeared to him in isolation; everything formed a system of coherent, solidary signs. This accounted for the mysterious lucidity of his conversation. He was thus led effortlessly to employ analogy as a literary source of imagery. As for analogical examples, he left us admirable and exquisite specimens. His notes on dance, for instance, form an astonishing collection. In his use of allegory, Mallarmé approached Wagnerian conceptions closely. That curious essay, Richard Wagner, rêverie d’un poète français, precisely fixes the degree of contact between poet-musician and literary symphonist, whilst marking their divergence. For Mallarmé, though advocating style’s musical development, shunned the confusion of poetry and music that Taine had predicted, insisting these domains remain absolutely distinct—one imaginative, the other sensory. Which brings us to his ideas on verse.

He did not regard the conventional distinction between verse and prose as fundamental, for this reason: verse has traditionally been seen as distinct from prosaic, everyday language, as the sole literary medium. (The word “prosaic” in its sense of vulgarity reveals prose’s former standing.) Verse constituted, through its very forms, a reserved language. But Mallarmé, insisting that the separation between art and common usage should distinguish not verse from prose but written from spoken language, saw verse and prose as equally ennobled, raised together to the status of aesthetic dialects. The rules of verbal music and varied grammatical cadences belonged to both. What established a text’s lyric current, in his view, was primarily the marriage of verbal harmony with syntax. “Poetic song” springs from the encounter of these two linguistic qualities, and artistic language ceases when they part company. The distinctive features of verse, for Mallarmé, lay chiefly in typographical arrangements, to which he accorded particular significance. He regarded the white spaces between stanzas and the use of line breaks as musical notation. Punctuation equated to the rests, sharps and quavers of music, to be employed analogously. Finally, he maintained that verse constitutes a single word; “from several vocables,” he says, “verse remakes one total word, novel, foreign to the language and quasi-incantatory.” Thus he conceived regular verse, founded on rhyme as rhythmic principle and verbal sonority as lyric principle, with breathing pauses at line-ends or enjambments. This represented for him the grand classical mode of expression, and he scarcely countenanced free verse save as respite or playful adjunct to poetry’s ancient form. Near life’s end, as I mentioned, he experimented with a compromise between verse and prose, publishing an example: an attempt to replace punctuation with typographical gradations, varying letter sizes according to phrasal importance. In verse, Mallarmé rarely admitted punctuation, believing line breaks and intervening spaces—which limit breathing and thus natural delivery—punctuated better than any prose markings. Such, broadly, were Stéphane Mallarmé’s principal ideas concerning stylistic form and the constitution of an artistic language. Symbolism, allegory, allusion, fiction—expressed through musicality and perpetual syntactic suppleness, remarkably close in his case to English syntax—these were his working materials. It remains to describe the œuvre to which he sought to apply them.

*

* *

Mallarmé regarded verse as a form of thought suspended between speech and music, and held this hybrid expression to be the cornerstone of the total work of art. Indeed, he recognised only two legitimate art forms: the book and the theatre—one addressing the crowd, the other distilling the crowd’s impressions and returning them to the individual. In his vision, verse served as the common tongue between these twin conceptions.

Verse was his chamber orchestra, his music in miniature—the vital spark of any true work.

In the work as Mallarmé envisioned it (and here lies the secret of his Wagner worship: the Ring cycle alone approximated his ideal), word, gesture, décor, ballet and musical expression had to achieve perfect fusion. Verse became the voice of consciousness itself—of the thinking subject, of humanity. Through verse, the drama’s ideas found utterance, and since every idea bears witness to the divine and thus partakes of religious essence—becoming prayer—rhythmic, musical verse expressed these ideas in keeping with its ancient calling as the language of the sacred and abstract. Verse embodied the ideological and intellectual dimension. The symphony, constructed on Wagner’s leitmotiv principle, conveyed sensation and passion. Gesture, through the combinations of mime, provided the active element. Ballet animated the décor, representing nature’s participation in human emotion—whether massed at the rear of the stage as living scenery, or releasing individual dancers to flutter like sensations around the protagonist. Thus, as man articulated thought through verse, the mime enacted the gestures his words commanded, ballet expressed these actions’ reverberations in nature, and music voiced the drama’s overarching emotions—rather like the Greek chorus—whilst determining both the mime’s movements and the ballet’s evolutions. The tone and rhythm of verse, that central element, governed recitative and orchestra alike.

Here we have the very theory of Wagnerian drama, save for one crucial distinction: the character retains primacy, with music serving literature rather than claiming equal partnership as in Wagner. Mallarmé further faulted Wagner for grafting his original genius for passion and art onto ready-made legends—”subjects” for development—rather than creating fresh literary and ideological themes from his own imagination. The French temperament, Mallarmé rightly observed, instinctively recoils from received legend. His symbolism demanded constant renewal and rejected any “treatment” of familiar myth, however wondrous.

Dance, for Mallarmé, both animated the décor and emanated from the character’s inner life. Ballet shuttled between hero and witnessing nature in perpetual exchange. “Everything in theatre,” the poet declared, “operates through reciprocity, always in relation to a single figure.” Such is the law of any system rooted in individualism. The dancer—that near-unreal, prestigious being—exists outside life proper. “She is not a woman dancing, for these combined reasons: she is not a woman but a metaphor condensing some elemental aspect of our form—sword, chalice, flower—and she does not dance but rather suggests, through her leaps and contractions, through corporeal script, what would require paragraphs of descriptive dialogue to convey in prose.” In Mallarmé’s ideal theatre, ballet superseded those descriptions of reality he deemed unliterary. Dancers became signs bearing attributes—living chess pieces without independent existence—elements in an animated hieroglyph etched against the ballet’s painted drops.

Mallarmé devoted an exquisite passage to the special case of Loïe Fuller, who abolished the conventional backdrop, replacing it with flowing, coloured silks that responded to her dance rhythms, enveloping her, becoming both costume and landscape—thus supplanting dead canvas and cardboard with living form. Here Mallarmé recognised a precious innovation for his dreamed-of intellectual art.

This theatrical conception approached that of symphony and fugue: symmetry, order, and perpetual reciprocity should govern all aesthetic expression within it. Mallarmé knew perfectly well what attention, what mental agility such performances would demand. Yet each spectator, he argued, takes what pleases or reaches them from any spectacle. An orchestral performance stirs vague pleasure in some, enthusiasm in others, whilst initiates and natural musicians grasp themes, timbres, and instrumental interplay that escape the layman—who nonetheless finds satisfaction in the experience. Every seen thing, he maintained, contains latent profound joys that observers discover according to their capacities: why dwell on this? Complete theatre, in any case, must encompass all these logical elements. As for the crowd, Mallarmé deemed it essential to theatre, and here his mysticism emerged. The fundamental dramatic subject was, for him, singular: beneath myriad anecdotes lay the same story—conscious humanity confronting nature. “The moment I see,” he would say, “a lady and gentleman discussing at curtain-rise adventures that might befall me, theatre ceases to exist. Like the peasant, I feel I’m eavesdropping on private conversation.” Character comedy and the entire psychological theatre thus held no literary validity for him—mere chat, explanations of daily life devoid of artistic merit. From the first moment, everything must be elevated to an abstract, universal plane, transcending time—”as the raised stage floor symbolises,” he noted. Then began Man’s exhibition, solemnly orchestrated by the poet’s anonymous genius, before his assembled fellows: a kind of mass, where crowds gathered to watch one of their own voice pure ideas. All that the assembled individuals could not personally embody—wealth, beauty, inspiration—the stage hero incarnated, and they came to recognise humanity’s nobility within themselves before returning to the street as uniformly dressed pedestrians. The dramatic hero stood as the true democratic prince of modernity, ringed by a hemicycle of self-effacing figures, mute and dressed in black. In concerts—whose recent flowering in democratic society Mallarmé saw as striking confirmation of his thesis—the conductor played a role analogous to the actor’s.

At each Sunday concert, Mallarmé observed, crowds entered, sat, fell silent, and after a week’s containment in quotidian labour, deposited amongst themselves their dreams, their yearnings for faith and beauty, their exaltations. The orchestra was fashioned from these elements, its melody expressing individual reveries back to listeners who recognised them and ceased, in a sense, to exist as separate selves—ecstatic, lost in beauty’s surge. “How is it,” Mallarmé wondered, “that this multitude, sated with daily existence, feels the instinct—does it rest on instinct?—to suddenly, leaping literary intervals, confront the Ineffable, the Pure, poetry without words?” From this theatrical and orchestral magnetism he concluded that crowds could perfectly well comprehend a symbolic fusion of the arts and accept these gatherings’ religious character, responding with the same obscure reverence to special costumes and attributes as to liturgical symbols and priestly vestments.

The book, for Mallarmé, compressed all these conditions into miniature form for the solitary reader. It contained the scenic elements in embryo, save ballet, which metaphor replaced. The book was “the spiritual instrument,” action’s supreme mode. “No act,” Mallarmé insisted, “surpasses the thought that inspires it, and thought is fundamental.” This conviction produced his much-misunderstood pronouncement, wrongly dismissed as mandarin dilettantism: “The world exists to culminate in a beautiful book”—meaning “the hymn of all interrelations.” Similarly, he explained that the sense of analogy generates all intellect; therefore, we should express not objects themselves but their mutual relationships and their connections to the ideological universe. When questioned about anarchism and propaganda by deed, he replied: “I know but one bomb—the book.” He so exalted it that it became for him the very emblem of human genius, and he despaired at modern volumes corrupted by journalism’s influence. “The newspaper’s influence is pernicious,” he wrote, “imposing upon literature’s complex organism in book form a monotony—always that insufferable column one merely distributes across pages, hundreds upon hundreds of times. But must it remain so? Let me digress (for the work itself will better exemplify) to satisfy curiosity. Why shouldn’t a surge of grandeur, thought or emotion—a considerable sentence pursued in large type, one line per page in graduated positions—hold the reader breathless throughout, summoning their full attention, whilst subsidiary explanations, complements, and derivatives of the central thought cluster around it according to importance—a scattering of flourishes?”

This typographical transformation, outlined in the curious note I’ve quoted, Mallarmé attempted only in the poem I mentioned earlier, of which critics received no copies—perhaps his final completed work. Such a conception necessarily limited the book: like Poe, Mallarmé envisioned a condensation of thought and emotion—a spiritual vade mecum, brilliant, profound, and brief, its concentrated symbolism offering themes for the reader’s personal meditation.

Here, broadly sketched, stands Mallarmé’s aesthetic—a complete system addressing art’s connection to metaphysics, the fusion of arts, literature’s proper object, the renovation of its means, syntax, poetics, symbolism, the book, drama, ballet, the poet’s social role—all unified by a mystical aesthetic vision. Whatever one’s enthusiasm for this hypothesis, its logic, architecture, and robust construction command respect. It bears the stamp of absolute idealism: whilst Hegelianism and its derivatives through Fichte and Wagner claim adherents, none can ignore Mallarmé’s unique attempt to apply their doctrine to letters and resolve the famous antinomy between “art for art’s sake” and “art for morality” through a mystical element that reconciles poet and public in shared lyrical ascent toward the Divine. Mallarmé’s system—the term is not excessive—sprang from an extraordinarily pure, contemplative, northern soul, drawing far more from English and German than French genius. He connects more closely than one might suppose to Goethe’s worldview and stands very near that Edgar Poe whom he penetrated so brilliantly—one might say he follows Poe chronologically through Baudelaire. Tennyson and George Meredith also offer points of comparison: from the former he shares a certain pristine sweetness in lyricism, from the latter that profound, serious subtlety and rare, barely accessible quality of work. Yet he remained quintessentially French, and perhaps only his intimates grasped this paradox. No one carried himself with more Gallic flair than Mallarmé. His bearing, his hospitality, his manners, his courtesy belonged to the eighteenth century; he told anecdotes like a Regency memoirist. He adored Louis XIV style and felt passionate about Impressionism—that most French endeavour, most true to our racial genius, that our painters have undertaken in half a century. Yet so complete was his separation of writing from daily life that this chasm, which struck all his acquaintances, probably never troubled him.

This aesthetic deserves a full volume. We must seek it in the meditations and notes Mallarmé left us and—I stress this—in his conversation, which illuminated infinite examples and clarified its subtlest difficulties. The logical rigour governing this artistic vision will certainly perplex many minds unaccustomed to conceiving literature in such elevated, complex terms.

For those who seek mere entertainment or even emotion—and the masses ask no more—Mallarmé’s demands will seem excessive, his desires opaque. Such reform challenges both public’s ingrained habits and storytellers’ conventions. It means swimming against a massive tide—yet Mallarmé did so with remarkable constancy, fully aware he offered reflections far too demanding, content to remain consistent with himself whilst never disparaging other writers whose work he disavowed even as he eagerly savoured their beauties. No one ever heard Mallarmé mock or denounce a book: however vapid, he discovered with gentle charity some interesting or worthy aspect. This man, excommunicated and ridiculed throughout his life, never knew bitterness or cutting criticism. At most he allowed himself a sly, smiling humour, as measured and refined as everything about him. The publisher’s note he composed for Divagations exemplifies this: “Under this possibly ironic title, M. Stéphane Mallarmé collects pieces made famous by the outcry they provoked: accusations of incoherence, unintelligibility… The public will find it a curiosity of our age to see how a writer, clear-sighted and direct, gained notoriety contradicting his qualities simply by excluding clichés, finding the proper form for each sentence, and practising purism.” That “possibly ironic” and “notoriety contradicting his qualities,” set against the simple, proud conclusion, perfectly captures the writer’s mischievous courtesy.

Mallarmé’s supposed obscurity stems purely from inattentive reading—anyone approaching him as they would a journalist would grasp his theories no better than they’d understand Kant or Spencer browsed in a café. The journalists who first broadcast these vague charges barely examined his work. Yet we needn’t perpetually endorse such chroniclers’ verdicts and overlook one of contemporary French literature’s most serious and daring aesthetic theorists. Critics conveniently retreated to attacking Mallarmé’s very style. We’ve seen detractors repeatedly take refuge in this fortress when pressed to admit that his ideas, however austere, tendentious, or rigorous, remain fascinating, coherent, and clear. We must emphasise that Mallarmé produced virtually nothing according to his system. The occasional sonnets he published were exercises—testing his theories about replacing punctuation with line breaks and white space (hence those comma-less sonnets that so alarmed critics); testing inversions whose potential he believed far exceeded conventional usage; testing word-music and rhythmic variation. Hence those convolutions and ellipses that startle even fellow writers.

Yet what art lacks such experimentation? Show the public a Rodin sketch or Manet study without context, and they’d never divine these artists’ greatness. Play someone even musically receptive an isolated violin part from a Beethoven symphony, and they’d likely miss Beethoven’s genius entirely. These technical studies interest mainly specialists; Mallarmé published them primarily for linguists and poets. His articles, pitched between conversation and his conceived style, often read like addresses to an invisible interlocutor or monologues. Examining them reveals precisely the qualities Mallarmé claimed: he excludes clichés, moulds each sentence uniquely, and practises purism. His elliptical, nervous phrasing—almost formulaic—approaches philosophical discourse. The present tense dominates; sentences possess something arrested and taut in their contours. Yet internally, an astounding variety of constructions creates rare balance and suppleness, and this dialectician’s language illuminates itself, even in demonstration’s most arid moments, with marvellous imagery. Terms display unwavering precision. The sole eccentricity that might unsettle readers lies in Mallarmé’s varied deployment of verbs, which he positions as the sentence’s culmination through bold inversions, often where least expected. Note too his capricious substitution of infinitives for present participles. Yet everything remains perfectly correct and coherent—Mallarmé’s personal touches no more exceptional than, say, Saint-Simon’s elliptical compression.

I’d wager that a Saint-Simon fragment, dropped without warning between newspaper advertisements or gossip, would create the same effect as Mallarmé—just as a Mycenaean gate-lion or Serapeum colossus at the Salon would provoke no less bewilderment than Rodin’s Balzac, which descends from them. Place and fashion heavily influence these facile charges of obscurity. Here’s a sample of Mallarmé’s allegedly “incoherent” style, opening his essay on ballet:

“La Cornalba enchants me, dancing as though undressed—that is, without gauze’s drowsy, floating presence offering semblance of support for rise or fall, she appears summoned into air and sustains herself there through her person’s pliant Italian tension.”

I cannot say whether a writer must be mad, mystifying, decadent, or wholly immoral—as many long maintained—to relish such a sentence’s craftsmanship. But its movement, its idea, its balance, the suspended “dancing as though…”, the explanatory “that is”, the placement of “Italian tension”—these are qualities that would surely have delighted Flaubert or anyone with feeling for literary art. Everything here rings true, simple, harmonious. Scarcely any accomplished prose stylist, seeing this single sentence, would fail to recognise a peer.

Readers turning to the prose poems, to Hérodiade, the Apparition, Les Fenêtres, the Pages series, will discover throughout traits of masterful synthesis and metaphors of austere beauty.

*

* *

What will remain of Stéphane Mallarmé? Let us first dispense with “Mallarmism”—a journalistic fiction. I trust I have made abundantly clear that Mallarmé was a man without disciples, absolutely beyond imitation, for nothing in his work can be extracted piecemeal, and whoever might appropriate his system would need to reconstruct everything to their own specifications, achieving an originality equal to Mallarmé’s own. The author of L’Après-midi d’un faune stood alone, a complete individual without counterpart among his peers. Everything about him—his manner of reception, his bearing, his ideas, his very existence, his writings—proceeded from a thoroughgoing originality that bore no resemblance to anyone else.

Time did not permit him to realise a complete body of work. We are left with his system, both spoken and adequately recorded, the memory of his august personality, and the poems of his early period—works of considerable merit that will claim their place among the most inspired and singular achievements of French literature. The supposed leader of the decadents led no one; rather, he was friend to a handful who shared his passion for the same intellectual pursuits. The “prince of poets”—a title he bore without seeking it—shared with Paul Verlaine the admiration of a discerning few. Like Verlaine, he endured public scorn before gaining belated respect, accorded more to his reputation and demeanour than to any understanding of his labours. Here was an intelligence of extraordinary refinement, an organism honed to the point of suffering, a logician fortified against his own sensibility. Mallarmé bore the burden of holding his own lyrical impulse in check, whilst enduring accusations of creative sterility when only his scrupulousness occasioned this alleged impotence. He was, like Flaubert, a purist—and those who write understand what griefs and weariness that word conceals. Purism lies at the very heart of both the joy and anguish inherent in creation. The disease of perfectionism, like the absolutism of logic and fanaticism, springs directly from a sound and healthy mind: up to a point, such gifts confer tremendous satisfaction. Beyond that point, they become instruments of torture. We have heard tell of Flaubert’s agonies during his bouts of verbal delirium. Mallarmé’s sufferings will remain untold; he bore them with quiet nobility, and we know only that they prevented him from releasing his envisioned masterwork, and that he commanded upon his death that all his remaining papers be withheld from public view.

Yet Stéphane Mallarmé will endure in our memory. His sheer singularity, I believe, guarantees it; literature will preserve his name as it does that of Vauvenargues, who belonged to the same mysterious and proud lineage of visionaries, leaving behind a distinguished reputation and several profound works. A man cannot have been so utterly exceptional in his own person and simply be erased. His aesthetic philosophy will find no imitators—imitation is impossible. Nevertheless, in numerous respects, Mallarmé possessed the genuine insights of a seer. Poets will forever turn to him as to a matchless compendium of analogies and abstract meditations on the foundations of their craft. His observations, his metaphors, his comparisons will prove invaluable. On dance, particularly, he pronounced the last word. Metaphysicians and mystics will claim him still more readily as their own: this spiritualist poetry, suffused with mysterious pallor, these white dreams drifting above life, these musical pronouncements, this perpetually transposed and symbolic vision—all bear the hallmarks of mysticism. Novalis and Swedenborg are this dreamer’s true forebears. He stands as the final flowering of Hegelianism, the ultimate expression of that noble and otherworldly aesthetic. As a poet, his place is alongside Baudelaire, though with less bitterness and perhaps a more instinctive lyricism; as a theorist of art, Mallarmé represents the direct impact of Wagner upon France. That fascinating experiment with vers libre, which introduced explicitly musical elements into traditional prosody, emerged from Wagnerism whilst taking English poetry as its model. Mallarmé, through his sympathy with Wagnerian aesthetics and his natural affinity with English lyricism and syntax, positioned himself at the very confluence of these two streams flowing into French literature. Here we discover the source of his universal appeal among younger writers. To this we must add his personal magnetism—quite exceptional—and the example of a supremely noble life.

1898.

THE MEMORY OF MALLARMÉ

Every man who rises meets with harsh judgement. “We are forever praised or blamed, never understood,” as Nietzsche says somewhere. But it seems to me that no one in our age has been more harshly judged than my master. I should like to attempt today to establish precisely what endures of Mallarmé.

Consult the press of his time and you will discover a wealth of glaring errors, fatuous mockery and abuse on one side, with sycophantic praise and protestations of admiration on the other—yet remarkably few cogent reasons for either this youth cult or this press hatred. All that clamour has died away: Mallarmé’s name is seldom spoken now. He wielded considerable influence in letters, to be sure, but it was an influence essentially personal in nature. The magnetism of his presence worked like a charm: men who had savaged him in print would encounter him, exchange a few minutes’ conversation, and depart mortified and contrite. One sensed oneself in the presence of a being whose inner life had achieved an extraordinary degree of intensity, whose spirit had been refined with such exquisite art that one could not approach without reverence. This created a cordon of respectful distance around a man who was, for all that, simple, generous, utterly without pomposity, and the first to laugh at the snobbery his personality inspired. The understated ease, the proportion, the precise dignity of his whole bearing would never have deserted Mallarmé anywhere on earth. Wherever he went, he was a prince.

I must beg to be taken at my word in all this, as we must trust those who heard Chopin play or Malibran sing, or those who lived in blessed intimacy with César Franck—for it is over now, and the witnesses to such beings are vanishing one by one. This extraordinary charm of Mallarmé’s was recognised by a select company of French artists and several illustrious foreigners who counted it an honour to be received in the decidedly modest flat of one they hailed as pure genius, at the very moment when the hack journalists were using him for target practice and any pedant felt qualified to improve his style. Mallarmé remained unknown to the many, first because the aesthetic and linguistic problems that consumed him are comprehensible only to the few, and second because he lived in retirement, moving in a small circle and maintaining the most profound distaste for personal publicity. Never would he have stooped to exercise his right of reply in some rag that lampooned him, and nothing that preoccupies literary folk existed for him. He had made his peace with poverty and incomprehension: if glory came to him, if people sought him out and loved him, it was without his asking. This noble bearing, free from both bitterness and repudiation of his times, was the mark of a man who held the loftiest conception not of his talent but of his conscience, and it explains why Mallarmé’s quite extraordinary personal magnetism remains so little understood even now.

At bottom, it mattered little to this subtle contemplative that he had won the devotion of Whistler, Degas, Berthe Morisot, Rodin, Monet, Banville, Manet, Renoir, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, and a select band of young men, several displaying the finest gifts. What he needed was an assiduous and scrupulous biographer at his elbow, rigorously and faithfully impersonal, recording everything, trivial or significant facts and words alike: such a chronicle of Mallarmé’s life and conversation would have made an incomparable document. I am not alone in feeling this keenly and regretting its absence. Not only did Mallarmé’s uncanny gift for instantaneous association of ideas lend his conversation on any topic an irresistible fascination; not only did his judgements, delivered with authority and precision yet with unfailing courtesy towards others’ views, open vistas unknown and invariably reveal some hitherto unsuspected truth; but even the most casual remark, the most ordinary gesture of daily life, bore his special stamp whilst remaining entirely natural. And it was precisely there, in the most commonplace moments—in how Mallarmé showed a visitor out, how he shook hands when parting from a friend at a street corner, how he remarked some trifling incident in the crowd—that one caught, in a flash, the true measure of his phenomenal originality.

No one in his circle possessed the requisite naïve ordinariness to record these trifles that compose a living portrait. The artists around Mallarmé were sophisticated aesthetes, dreamers absorbed in their own work, who retained only their master’s pronouncements on art. They shrank from transcribing his words, fearing to offend by trailing him with notebook in hand like journalists. They had known him at different periods, some having drifted away, others arriving rather late, none feeling equal to preserving all that Mallarmé had uttered in twenty years of marvellous discourse. I myself knew him only from 1891 to 1897, and scruple led me to destroy a work of this kind I had begun, though I had already set down a considerable number of those miraculously witty or lyrical parables, supremely elegant and profound, that my master would improvise whilst leaning against the mantelpiece in his little dining room in the rue de Rome, through the haze of cigarette smoke. In any case, he was too fastidious not to prefer that his talk remain the pleasure of a fleeting hour, and it would have been tactless to compile such a record without his consent. These considerations have robbed us of what would have been nothing less than a great man’s intellectual testament. Now it can never be realised. It must remain an oral tradition. Gustave Kahn, Henri de Régnier, Pierre Louÿs, André Gide, Ferdinand Hérold, Édouard Dujardin, Teodor de Wyzewa, Paul Claudel know fragments as I do; Marcel Schwob, Whistler, Samain knew others; they are gone, and we too shall vanish in our turn. We all assumed Mallarmé would enjoy great longevity. Had we foreseen his sudden, untimely death, perhaps one of us would have acted, and we should possess a modern Phaedo.

No one ventured to play Plato to this Socrates. A diligent scribe would have sufficed. But the truth is that the poets who thought they loved Mallarmé best did not love him in the right way. Seated before him as before an idol, they barely dared respond, whilst he, unaffected and cheerful, asked only to sharpen his wit through debate. I recall how on my first visit to the rue de Rome, disarmed by his kindly face, I thought it perfectly natural to counter with an objection some thesis he was advancing to a group of silent writers: they blasted me with their eyes, to my astonishment—this twenty-year-old upstart who had presumed to speak in the sanctuary.

Later, in informal conversations in Paris or at his country retreat at Valvins, Mallarmé often mentioned this curious cult to me with gentle mockery. They wanted to worship him in a hermetic chapel, and too many reduced this great poet to a Delphic oracle, a deity who must remain sealed off from the world and confined to the endless dream of the Masterwork. Thus arose the legend of his sterility, his reputation as the Balthazar Claës of literature. True, he shared with Flaubert, Elémir Bourges and others the love of patient perfection, the scruple of the purist and the willingness to devote twenty years to a book whilst embracing poverty and neglect, but nothing will shake my conviction that excess of veneration trapped him in a dilemma from which he would gladly have escaped. This whole dimension of my master’s character is therefore doomed to fade into oblivion. No one even thinks to collect his letters, those marvels of wit, grace and depth; they think it splendid to entomb the magician in his beloved mystery. Perhaps posterity will judge that it would have been better to champion this great memory rather than abandon it without a struggle.

Meanwhile, I observe that enough remains of Mallarmé the writer to honour his memory, and surely we cannot carry reverence and discretion so far as to destroy what he published. Now, examining his published work, we find the following:

The poems entitled Les Fenêtres, Les Fleurs, L’Azur, L’Apparition, Le Guignon, the hundred-odd lines of the Hérodiade fragment, the Toast at Théophile Gautier’s tomb, seven or eight sonnets—these rank amongst the finest poems in the whole of French literature, worthy to stand beside Baudelaire without being derivative. And by “finest” I mean that in the broadest sense, setting aside everything the symbolists of 1890 cherished in them, even deliberately excluding the strange and exquisite L’Après-midi d’un Faune, they are universally intelligible, as lucid as Racine, and such as only a great poet could have conceived. Grant that the rest is obscure, incomprehensible, grant everything his detractors said about those linguistic and syntactic experiments Mallarmé conducted for himself and a handful of initiates. Here are three or four hundred lines of pure beauty. One needs far less to achieve immortality, and whoever reads them, in whatever age, must acknowledge them as Baudelaire’s equals. The same holds for the prose poems like Plainte d’automne, Frisson d’hiver, Pauvre enfant pâle, La Pipe, and above all that magnificent Phénomène futur which, in its nobility of conception and splendour of form, stands comparison with the most celebrated French prose, and which is less Baudelairean than the others, more quintessentially Mallarméan. Throughout, a voice like no other’s.

The translations of Poe’s poems are, even his critics concede, masterpieces of artistic transmutation. Then there are the aesthetic writings gathered under the titles Pages and Divagations, including the discourse on Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, the notes on ballet, the meditation on Wagner, the lecture on Music and Letters, the impressions of concerts and theatre. Here, in a style whose sinuosity, complexity and unconventional syntax I freely acknowledge (though it remains rigorously Latin in logic), yet where luminous phrases flash forth—in this refined style, obscure not through slack or imprecise diction but through excessive compression and economy, Mallarmé laid the groundwork for a neo-Hegelian aesthetics. And whilst this aesthetics remained sketched rather than fully realised, it nevertheless sparked countless ideas in artists who now receive the credit. Here we find a powerful system of correspondences, a profound grasp of the laws governing artistic creation, criticism raised to its highest power, and, when all is said, the last coherent aesthetics attempted in France before our present chaos. No one has packed more thought into fewer words. Mallarmé conceived the infinite plenitude of the universe with such intensity that nothing presented itself to his mind in isolation—all was a system of interconnected signs. He regarded verse as an intermediary dialect between music and prose, believed that mastery of style lay in exploiting the variability of syntactic combinations, and withheld the wealth of his thoughts until he had discovered a genuinely novel mode of expression. Two months before his death, he wrote to me that he was above all “a desperate and wretched craftsman”.

Such an approach to “the act of writing” drives a man towards loftier and more complex ambitions than mere “clarity”. No one asks whether Kant or Hegel are “clear”. One either takes the trouble to analyse them or leaves them alone. They are clear enough, in that their logic unfolds with rigorous coherence; it is their subject matter that is rarefied, not obscure. Henri Poincaré’s books are perfectly lucid and consistent: yet he corresponded across Europe with five or six mathematicians, and these scholars understood one another perfectly on matters utterly “obscure” to us. The notion that literature should be accessible to all simply because it appears to use common language is a grave misconception. A transcendental literature exists that legitimately transcends the immediate demand for “clarity”, and our craft harbours its mysteries. Mallarmé devoted himself exclusively to these, and this is how we must view his metaphysical and lyrical enterprise. The English, after initial resistance, have been fairer to their great and subtle Meredith. “Even geometric propositions,” Pascal observes, “become feelings”. And Pascal himself is not always “clear”, nor are the mystics. In how many bestselling novelists, long-running dramatists, or salon academicians shall we find, the day after their death, when oblivion crashes down with the spadefuls of eulogy, what I am moved to rediscover in Mallarmé, who leaves us a jewel casket? He need only have cashed in his art by simply transcribing those daily conversations of exquisite charm: with his personal magnetism he would soon have won fame and fortune. But here was a man of profound integrity who preferred to live by teaching English and swallow the bitter pills that Taine too had known and never forgotten. This simplicity, this probity—not merely writing only when one has something to say, but judging, after thirty-five years’ study, that one still cannot say it well enough—is not this alone worthy of admiring respect in an age when everyone scribbles? This prince of the spirit regarded literary art as sacred. Only the muddle of a literary crisis could have yoked him with Verlaine. Though fond of one another, united in public rejection and the admiration of an elite, they stood poles apart. One was plebeian, instinctive, innocent of theory, sustained only by his passion for independence and an almost street-wise common sense. The other was aristocratic, cerebral, self-possessed, more logician than creator, and bred as they breed no more. One had the blood of pure French stock coursing through his veins, for better and worse. The other was a Lakist and a Hegelian. Mallarmé might have been our Keats and our Ruskin, bringing the gifts of Fichte and Schelling to bear on higher criticism, had he arrived when the public, stupefied by naturalism and hoodwinked by spurious psychological fiction, could have truly grasped the need for such criticism and such poetry. Mallarmé left an indelible mark on those who knew him. For my part, if the least among them may speak thus, I call him my master because before meeting him I knew nothing of certain secrets of our art, and understood poorly, with youth’s blind confidence, the gravity and responsibility inherent in the awesome privilege of writing. I believe I owe him nearly everything in moral terms, having learned through him absolute reverence for art and scorn for success bought by compromise; and his stylistic principles were so remarkable that they form a hidden armature, infinitely flexible and adaptable, even for wholly different achievements in verse or prose.

Rodin said, returning from my master’s funeral: “How long before nature produces another such brain?” Perhaps she is fashioning one somewhere, but we cannot yet name the place. Even discounting the incomplete and over-ingenious portion of his researches, even without experiencing the imperiously persuasive force of his presence, those who survey what survives of Mallarmé will be moved to acknowledge that none of our living writers has more surely secured for himself a glory limited, certainly, but unassailable. And many who have invested all their glory in life’s lottery would secretly trade places to leave behind the memory and the perfect fragments he bequeaths us, and to have been revered so deeply.

This is one of 50+ rare French literary texts translated into English for the first time on this site.