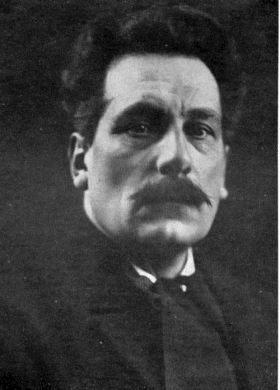

French poet René Ghil (1862-1925)

A reader who has thus far worked through every text offered above in the section Mallarmé in Memory should, I believe, be forewarned before proceeding to this final piece, translated here for the first time from Ghil’s 1923 volume Les dates et les œuvres; symbolisme et poésie scientifique, where an entire chapter is devoted to Mallarmé. Whereas the preceding texts were straightforwardly eulogistic, what follows is not. On the contrary, it takes a critical view of Mallarmé—though, to be clear, of Mallarmé the poet, the Master, as Ghil still reverently calls him. It is a well-established fact of the literary history of that period that Mallarmé and Ghil were initially drawn to one another as kindred spirits of a sort; that Mallarmé wrote a celebrated Preface to Ghil’s Traité du Verbe; that Ghil was a regular at the legendary Tuesdays; but that they eventually fell out owing to their fundamentally divergent aesthetic views—and not merely aesthetic ones, given that Ghil’s entire outlook was decidedly that of a positivist and scientifically minded poet. I would suggest, by way of introduction, that readers first consult three scholarly articles, the links to which I provide below:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/40552575

STÉPHANE MALLARMÉ

The First Body of Work

Mallarmé himself — that genial host of the Tuesday-evening gatherings in the rue de Rome — delighted in recalling how, at about twelve years old, his one burning desire had been to enter the priesthood. Though another, secret ambition also gripped him: to displace Béranger in the public’s affections — that old Béranger who sang of his dear Lisette and the Man in the Grey Frock-coat who “sat himself down right there, grandmother!” He had encountered him at the house of mutual friends: “Now there’s a great poet!” someone had assured him.

The first wish, we might venture, expressed the true, instinctive bent of his soul. And truly, it was as something very like the supreme episcopal guardian of an occult Art that he came to preside — his gaze absorbed in contemplation of that broad, enchanted violet stone set within the Sacred ring:

Eau froide par l’ennui dans ton cadre gelée…

[Cold water frozen by tedium in your frame…]

Whilst the poems Mallarmé produced during that first decade — from 1862 to roughly 1873 — undoubtedly announce a poet of exceptional gifts, one whose Word resonates with rare sonorities and whose imagery often achieves a terse, logical distinction entirely his own, his sovereign personality had yet to reveal itself fully. Regarding those nuanced sonorities of his verse, we might recall Leconte de Lisle’s observations on Les Fleurs du Mal: “Everything conspires towards the total effect, leaving in the trained ear something like a masterfully orchestrated reverberation of precious, resonant metals, and before the eyes, magnificent colours.” He added that Baudelaire’s volume “imprinted upon the mind visions of terrible and mysterious things.” (Revue Européenne, 1861.)

From Mallarmé’s Verse, however, there persisted vibrations of still more rarefied metals, though we cannot yet claim it possessed, as it later would, that quality of immaterial, crystalline tremor! His colours never achieve Baudelaire’s blazing luminosity: more subdued, they reveal finer gradations, tending — alongside the Word’s more muted resonance —towards melodious musicality. Hear how the tender Apparition sings:

La lune s'attristait. Des séraphins en pleurs Rêvant, l'archet aux doigts, dans le calme des fleurs Vaporeuses, tiraient de mourantes violes De blancs sanglots glissant sur l'azur des corolles… [The moon grew sorrowful. Weeping seraphim, Dreaming, bow in hand, amid calm vaporous Flowers, drew from dying viols White sobs that slid across the corollas' azure…]

But nowhere in Mallarmé do we encounter those visions of black and anxious torment that could disturb even Leconte de Lisle’s studied composure. Such visions were foreign to this serene temperament, whose reveries deepened at most into a tremor of overwrought purity — within that mirror-pool of solitude where Hérodiade glimpses herself: “that peculiar child!”, as her creator would say, shaking his head with characteristic equanimity!

Je m'apparus en toi comme une onde lointaine Mais, horreur! des soirs dans ta sévère fontaine J'ai de mon rêve épars connu la nudité… [I appeared to myself in you like a distant wave But, horror! on evenings in your austere fountain I have known the nakedness of my scattered dream…]

Our parallel between Baudelaire and the early Mallarmé is quite deliberate. Throughout these first poems, the sovereign sway of the author of Les Fleurs du Mal remains inescapable. Yet as we have observed, the uncanny, the violent, the soul’s storms and blasphemies — these run counter to Mallarmé’s very nature. Still, Baudelaire’s grip proved so compelling that Mallarmé fed his inspiration through Baudelaire in defiance of his own temperament! This borrowed inspiration yields poems like Les Fenêtres, L’Azur, Guignon (barely his own work at all), and possibly Don du poème, where something of Baudelaire’s so-called Satanism surfaces.

Direct echoes force themselves upon the poet. Consider this line from L’Azur:

Où le bétail heureux des hommes est couché

[Where humanity’s contented cattle lie]

— which plainly betrays the haunting echo of that verse from Femmes damnées:

Comme un bétail pensif…

[Like pensive cattle…]

Mallarmé reveals himself utterly taken with Baudelaire’s art of externalisation. And isn’t it remarkable, when one considers that art of meditation and inner re-creation which he achieves in his period of supreme personality? Yet one might argue that— whether acquired or innate to Mallarmé’s spirit — this concern with grounding the purest and most remote analogical nuances of the Idea in sharply delineated traits of reality persists throughout nearly all his work, even where those few real traits are, beyond their illusory transposition, deliberately veiled. I believe, then, in Mallarmé’s innate predisposition to anchor his meditation in tangible spectacle, in whatever features of Nature his Self — now philosophical — might choose to invest with ideal values. This spontaneous disposition emerges with stark clarity before his art attains its subtle complexity, whilst also becoming intensified through passionate engagement with Baudelaire’s art, whose force upon him proves overwhelming. So overwhelming that he borrows from Baudelaire the very themes of inspiration, going so far as imitation in poems like Le Guignon, whilst in Brise marine, the exoticism of L’Invitation au Voyage captivates the trembling admiration of Mallarmé, haunted by masts in harbours of half-glimpsed islands! Baudelaire’s spleen, too, infects him.

Yet in poems such as Les Fenêtres, L’Azur, and Le Guignon, we must note a Baudelairean tendency — inherited from Romanticism — towards violently externalised images and vocabulary, rendered in often startling compressions, tinged even with a kind of commonplace made tragic. Whilst the entire Parnassian school pursues noble and precious refinement of word and image — thereby losing touch with reality and life — Baudelaire plunges passionately into life, which he desires strange and breathless. More than this, he welcomes into his poetry the quotidian spectacle of existence. He was the first, in sudden flashes, to grasp the possibility of wedding modern man to his most familiar, most humble surroundings: he saw city streets, embankments, squares, rooftops.

From this springs an apt and novel vocabulary. Through him, as through Hugo though more viscerally, every word without exception enters the poetic realm. Everything depends on producing them artfully, and Baudelaire’s art in this regard displays extraordinary, flawless mastery — or rather, a circumspect craftsmanship guided by an exquisite sense of harmony.

Mallarmé finds himself seduced by this artistic introduction into poetry — wilful, almost insolent to its surroundings — of the vulgar word and image. Yet naturally he lacks that admirably balanced art, fruit of lengthy trial and patient refinement. Under the spell of that Model with the sly and subtle smile, he pushes too far! Hence, he writes what he would later disown, once all violent gesture and evocation had become antithetical to his true, disembodied nature:

Ainsi, pris du dégoût de l'homme à l'âme dure Vautré dans le bonheur, où ses seuls appétits Mangent, et qui s'entête à chercher cette ordure Pour l'offrir à la femme allaitant ses petits, Je fuis et je m'accroche à toutes les croisées… [Thus, seized with disgust at the hard-souled man Wallowing in happiness where only his appetites Feed, who persists in seeking out this filth To offer the woman suckling her young, I flee and cling to every window-frame…] Et le vomissement impur de la Bêtise Me force à me boucher le nez devant l'Azur! [And Stupidity's foul vomit Forces me to hold my nose before the Azure!]

Now, once Mallarmé has mastered an art equal to Baudelaire’s— indeed an art of greater consistency in its assurance and purity — the seduction nonetheless endures: that paradoxical employment of habitual, commonplace words from daily discourse. Words he must endow with soul (though excess of this concern, becoming mere technique, would prove his undoing), a soul rendering them forever alien to the multitude who nonetheless employ them daily. “Words have a soul,” Maupassant observes in his Study on Flaubert. “Most readers, and even writers, demand only meaning from them. One must discover that soul which reveals itself through contact with other words, which blazes forth and illuminates certain books with unknown light.”

This love of employing the most ordinary words in the most hermetic poem reached the point of paradox — yes, as it often did, for paradox is a Game, and Mallarmé frequently conceived poetry as a Game delighting in itself. I remember what he told me at Valvins, as we sailed beneath the angular canvas of his boat… He gently chided me for using learned words, or rather words in their primary, original sense: “Why? No,” his smile playful, “we must use everybody’s words, in the sense everybody thinks they understand! Those are the only ones I use. They’re the very words the Bourgeois reads each morning — identical! But here’s the thing” (his smile deepening), “should he encounter them in one of my poems, he no longer comprehends them! That’s because a poet has rewritten them”… I know, for the Master told me so whilst composing them, that he particularly applied this principle in three of his untitled Sonnets, beginning respectively:

Tout Orgueil, fume-t-il du soir… Surgi de la croupe et du bond… Une dentelle s’abolit…

The first sonnet presents a deserted chamber where the hearth expires in smoky evening light of sun and smothered torch, with a piece of furniture, a “console” concentrating all gleam in solitude beneath its flat, sepulchral marble. The second gradually evokes a delicate vase, precious glass from which no lips have drunk, which cannot even suggest through a kiss the perfume, in a rose’s dying breath: it stands empty… The third, we should understand, presents a “curtain” (not from a bed, as some have construed, for whilst this curtain might suggest a bed, no bed actually exists), and simultaneously a guitar, a “mandore”. As the verse tells us:

Dans le doute du Jeu suprême

[In doubt of the supreme Game]

the poet gradually develops an analogy between the absent bed, site of births, and the instrument’s ventral curve: a womb from which “Filially, one might have been born.”

These three Sonnets, as is well known, belong to Mallarmé’s final manner. They exemplify an art of ‘allusion’ that genuinely delighted him — as if to suggest that the Symbol amounted to nothing more! They are pure art and, yes again, poetic play. Their comprehension proves arduous, and one must admit to disappointment when, having grasped the riddle’s solution, one has understood. Let us not be surprised: in Mallarmé, aesthetic genius often mingles with ingenuity, applied to rare perception and the workings of primitive analogy…

— To continue. We have observed in Mallarmé a singular aptitude for Baudelairean art, though this aptitude, whether innate or acquired, immediately grows excessive through an almost total possession of his poetic sensibility by what seems his exclusive reading of Les Fleurs du Mal. We have also observed how this ascendancy directs Mallarmé’s very inspiration, how certain poems clearly present themselves as rejoinders to specific pieces by Baudelaire, whilst others, under the sway of this unique admiration, stand opposed to his own temperament in both conception and feeling.

Indeed, he then directs his poetic activity towards precise imitation of Baudelaire; like him, he divides himself between the Poem and the prose poem. He is, like Baudelaire, captivated by Edgar Poe and translates him. It appears that Mallarmé’s attachment to the poet of The Raven comes through Poe’s translator. Here too he seems permanently subjected to that most beguiling personality, for between Poe and Mallarmé there exist no genuine points of contact. The case had been different with Baudelaire, who sensed in the author of the Histoires extraordinaires a kindred genius, one that complemented certain ill-defined aspects of his poetic being. It is difficult to determine — can one even determine? — whether the encounter was necessary or merely fortunate, and perhaps we should rather say that Edgar Poe illuminated Baudelaire about himself?

The prestigious philosophical intellectuality of Eureka‘s poet is truly grasped only by the great Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, whilst Baudelaire’s romantic spirit is touched above all by the strange torment of Poe’s thought, which exteriorises a heavy, occult atmosphere charged with spiritualised visions.

Now, what preoccupation must have seized the eager minds of the new poets when confronted with Baudelaire, who imposed both himself and his literary predilections! Paul Verlaine, equally Baudelairean during the Poèmes Saturniens period, had in an enthusiastic article saluted, on behalf of the new Pléiade, the poet they recognised as their Master. We find mention of this article in one of Baudelaire’s letters (Mercure edition, 1907): the poet, affecting lightness — for surely it would be unseemly to bare one’s soul — professes astonishment at this enthusiasm which he declares “excessive”, whilst we sense him inwardly delighted, perhaps profoundly moved.

But no one felt or comprehended as thoroughly as Stéphane Mallarmé the poetic contribution of Les Fleurs du Mal‘s creator: his decade of poems proves it. Yet the mode of art and thought whose possibilities he would push to extremity and to which he would consecrate himself — the Symbol — he received and conceived from Baudelaire. Let me recall, from one of those letters published in 1907, the passage where Baudelaire, in passing, declares that Imagination, superior to execrated Science, creates universal harmony by establishing “mystical concordances” between the elements of the Whole.

(We must note again, regarding this assertion, his error —which became Mallarmé’s error and Symbolism’s error. Imagination, being an exercise of the Self, can establish only concordances relative to that Self, which will then analogically compose a universe reflecting solely its own imaginative sensibility. Only the experimental contributions of science can enable the creation of universal harmony, by lending concordances real and impersonal value as relationships between elements and between the Human and the evolving Universal, whilst preventing that latent survival of atavistic religiosity which, as we know, this epithet of troubled meaning— ‘mystical’ — conceals for Baudelaire and the Symbolists.)

Has Baudelaire elsewhere summarised his essential aesthetic so felicitously? Yet the expression of this Aesthetic — which determined an artistic concept of the emotive relations between Self and external world, a concept neither entirely explicit nor conscious — didn’t Mallarmé and the others find it superbly rendered in that oft-recalled poem, Correspondances?

Comme de longs échos qui de loin se confondent Dans une ténébreuse et profonde unité Vaste comme la mort et comme la clarté, Les parfums, les couleurs et les sons se répondent… [Like long echoes merging from afar Into a dark and profound unity Vast as death and vast as light, Perfumes, colours, sounds correspond…]

Within these verses lay the entire Symbolist theory in embryo: by developing them according to their inherent spiritualist aspiration, the movement would discover the complete range of Analogies that Mallarmé would nuance and dematerialise until the Idea became disembodied, stripped of every sign, if possible! Yet Verlaine, despite his enthusiasm, was never truly marked by Baudelairean aesthetics, nor do the various Parnassian poets bear its stamp. If we find this stamp so distinct and enduring in Mallarmé, it is because he alone possessed the capacity to assimilate the complete and intimate thought of this Art which, like all expressions of genuinely new and necessary thought, surpassed his generation’s sensibility and understanding.

We may therefore readily accept that Stéphane Mallarmé already harboured within himself, in more or less dormant energy, several of Baudelaire’s poetic virtues, particularly and primarily the gift of suggestion and analogy — or Symbolism, understood as divested of those philosophical intentions later refined or borrowed. We understand how naturally there occurred, from Mallarmé not yet master of a sustaining will, towards Baudelaire with his concentrated powers, a passionate transference! Through this complementary impulse, Mallarmé’s poetic qualities initially tend towards exaggeration, become troubled, even adulterated. And this period of “first Work” spanning ten to twelve years must, I believe, be seen as a search for equilibrium in a personality violently and intimately wrought upon, enriched in consciousness and in elements of poetic expression through contact with the Work of the premier Master…

But by what process, what ferment, what decisive event or external influence did the Mallarmé of the first period transform into the poet of Hérodiade and L’Après-midi d’un Faune? The poet also of Pître châtié and the Tombeau d’Edgar Poe? These poems mark the radiant dawn of his “second work”, which we might characterise thus: that henceforth Mallarmé’s Word had rather suddenly unburdened itself of the Baudelairean verb’s density, had purified itself of that somehow darkly magnetic atmosphere of Les Fleurs du Mal, creating instead its own atmosphere — subtle, vibratile, serene, and suggestive of a certain desert optimism, removed from the vibrations of surrounding wills and acts. As Baudelaire had written: “Poetry and progress are two ambitions that hate one another with instinctive hatred.”

From this period onwards — and the preoccupation is especially palpable in L’Après-midi — his poetry “contents itself with allusion to the reality of things or with abstracting their quality to incorporate some idea. On this condition soars the song that is the joy of being unburdened” (Divagations). Unburdened — the word comes naturally. The concrete element which, as we have noted, exists everywhere, even in the most “allusionist” poems, to support the poet’s analogies, increasingly blurs its contours; and what shimmers through is an abstraction, suggestive through its very vagueness. The ideal image of the thing supplants the real and living thing. When he says: a Flower — what he wishes to reveal is “the absent one from every bouquet”, namely its memory, suggested and as though beyond the gaze, pure idea, stripped of its sign.

Yet it appears that his prose poems from the first period betray, more than the contemporaneous verses, this tendency which dominates Mallarmé’s art. Might we detect here an influence from Poe’s poems? But then again, regarding this initial lightening of vocabulary and syntax — how singular that Mallarmé’s poetic prose should be, at every stage of his art, grammatically more abstract, more tortuous in concept and discourse than his verses themselves. The proof lies in his Divagations, and in that strange prose poem Un coup de dés which became his final page.

Whatever we make of this observation, it strikes me as worth recording. It suggests that at a certain juncture, Mallarmé’s original spontaneity in writing verse was deliberately bent towards postponement, a halt before achieving that writing of absolute purity he desired, according to rules he imposed and continually refined. And might not his preparation for this verse-writing have proceeded thus, through experiments in poetic prose from which, by successive eliminations, by suppressing details and through ellipses, he would extract that pure diamond-like expression he sought with ever-increasing purity, ever more immaterial?… Yet without labouring the point, that Mallarmé progressively stifled the spontaneous impulse of inspiration is undeniable. Here, indeed, he pushed to paradox. To me, to others, he revealed with satisfaction that certain of his late-manner sonnets were composed according to the bouts-rimés technique: he would choose his rhymes, write out the fourteen terminal words, then fill in the sonnet! Take, for instance, the sonnet beginning:

“Ses purs ongles très-haut dédiant leur onyx”

[“Her pure nails on high dedicating their onyx”]

and, as he confided to me personally, finding himself short of a word in the -yx series, he invented one — the word ptyx, to which he assigned the meaning of vase or urn, and whose non-existence he renders in the following line:

“Aboli bibelot d’inanité sonore”

[“Abolished trinket of sonorous emptiness”]

— But the true, the manifest catalyst for the poet’s transition to his second manner, to his second Work (without, however, deflecting his now-established concept of art), we must recognise in the influence of Théodore de Banville’s work: Banville, the sole figure to whom the author of L’Après-midi d’un Faune gave and would continue to give the title of Master.

The Second Body of Work

The two works of marked character in which Mallarmé first shakes off Baudelaire’s hold are undoubtedly the poems Hérodiade and L’Après-midi d’un Faune. Among his slender output, these poems remain works of capital value, of sovereign endurance.

Now, as I was saying, it was my view that the study and admiration of certain works by Banville had rather suddenly furnished Mallarmé with fresh elements for his evolution and, as it were, freed him from the dominion of the author of Les Fleurs du Mal. Granted, she still appears a strange “Flower”, as though of icy ardour, this Hérodiade whose repressed sensuality the poet conjures beneath jewels of proud tedium. She still partakes of the Baudelairean mode when she cries:

.. L'azur Séraphique sourit dans les vitres profondes Et je déteste, moi, le bel azur! [... The Seraphic azure smiles through the deep panes And I, for my part, detest the lovely azure!]

She still derives from it in “loving the horror of virginity”, in haunting those solitary palaces and parks where mirrors and stagnant waters gaze upon themselves, where the setting, fitting complement to Hérodiade herself, dons an impassive splendour of metals and precious stones… But what fresh melodious suppleness in the verse, what new mastery too in the cutting of certain lines, rendering them almost dramatic in their movement of thought! And throughout the poem, what loftiness of poetic tone, what sumptuous hieratic quality.

I said: dramatic. Whilst borrowing scansional techniques from dialogue poems such as Deïdamia or Diane au Bois, the poem Hérodiade is simultaneously a dramatic scene possessed of Racinian purity: an action whose every gesture has been intellectualised. The same purity marks Banville’s dramatic poems. Let us be clear, then, that it was from Banville the dramatist that Mallarmé took his cue…

Consider that delightful piece Diane au Bois, attending particularly to the character of Gniphon, the Satyr. Aflame with desire, pilferer of Silenus’s wine, maddened by visions of Diana-the-Huntress’s train in sun-swept glades, this Gniphon — plaything of those graceful, cruel creatures — nonetheless deludes himself. His relentless, maddening desire conjures a monstrously blissful dream, and he half-believes he has subdued them in his embraces! He wavers between two of them, unable to choose:

“Well then! Yes, both of them, so be it!”

“I’ve caught one — away!” the goat-foot cries in his frenzy… And Mélite, one of his quarry, having mocked him, hurls her pitiless laughter: “Farewell, lily!”

Now, the Satyr’s theme in Banville is, we observe, precisely that which Mallarmé unfolds in L’Après-midi d’un Faune. Beyond question, he has adopted it wholesale, compressed the episode into a kind of extended monologue alive with the panting faun’s gestures as he rushes in pursuit. At most, he has heightened the demigod’s delirious intoxication, who wonders whether his conquest wasn’t merely of vast clusters of grapes clutched against his breast!

The faun likewise pursues a pair — the dark one and the fair, two sisters… Rhythmic patterns, signature expressions from Banville’s poem resurface. Thus that “Farewell, lily!” — here it reappears in transparent echo, in these three lines of pure delirium:

Alors, m'éveillerai-je à la ferveur première, Droit et seul, sous un flot antique de lumière, Lys! et l'un de vous tous pour l'ingénuité. [Then shall I wake to that first fervour, Erect and alone beneath an ancient flood of light, Lilies! and one of you all for innocence itself.]

If we add that the Faun‘s eclogue was written at Banville’s express request for Coquelin to perform (though the performance never materialised), no doubt remains: Mallarmé is so beguiled by his Elder’s art and his solicitous, loyal friendship that he even draws inspiration from one of his poetic conceits — just as he had yesterday drawn wholesale inspiration from Baudelaire’s œuvre.

Above all, it is Banville the dramatic poet who enthrals him. Might we detect here the still-nascent principle of Mallarmé’s impulse towards theatrical expression? — impulses that Wagnerian thought would later remarkably amplify, surely crystallising that dream of the ideal Theatre about which the conversations of the author of Divagations, and the book itself, have afforded us glimpses.

Via Banville, then, he achieves the marvellous artistry of L’Après-midi d’un Faune. Yet it remains true that in this poem he attains his full individuality. What distinguishes it is that the image no longer stands forth alone, sharp and bare — rather, it emerges, as it will henceforth in all subsequent poems and sonnets, through a subtly graded series of analogies. The image becomes a compound of analogical images, progressively more intellectualised, releasing as its keynote the idea the poet had in mind, which must arise solely from an aggregate of allusions. This, and nothing else, is ultimately what Mallarmé understood by the art of the Symbol, what he articulates again at the time of the Huret Enquiry, as we have seen.

Meanwhile, the poet had bound himself to renounce those sweeping movements, those flights of verbal fancy (dismissed as mere outward show) that marked his first manner, romantic in the wake of Baudelaire. He reins in all spontaneity, withdraws into himself, distils his thought, and rather than releasing it in one surge through rhythmic emotion he dissolves it, so to speak, breaks it down into analogical elements only to recreate it within the measured tranquillity of pure intellect. His Word has shed its full-bodied resonance —inevitably, given his new mode of conception. These tones, now playing off one another in rapid succession, have lent the verse a scrupulously sustained and restrained melodic intensity, something quite unknown in our poetry until now.

Syntax and grammar edge towards Virgilian Latin, and the language will increasingly tend — fortunately, if only for a while — towards an almost agglutinative character…

This art, magnificently refined into something utterly personal in L’Après-midi d’un Faune, reveals its sovereign command and exemplary synthesis in the sonnet of the Swan… One might, I grant, detect in this Swan, trapped in the lake’s ice “for not having sung the region where one lives”, an echo of Baudelaire’s Albatross. What of it? The idea may be the same, yet this very kinship throws into relief the gulf between their two arts. Perhaps never has purer sensation been rendered of pride raised to the highest pitch of intellect:

Tout son col secouera cette blanche agonie Par l'espace infligée à l'oiseau qui le nie! [All his neck will shake off this white agony Inflicted by space upon the bird that denies it!]

Yet what mastery governs the poem’s entire architecture, where everything — vocabulary, music, colour, line and movement — conspires towards this rigid whiteness of the bird and the “sterile winter where ennui shines resplendent”, whilst the rhymes, dominated by the letter “i” — now piercingly sharp, now mellowed by fitting consonants — produce an almost palpable edge of frost and desolation.

This particular preoccupation betrays the attention Mallarmé had lavished on his theory of “Verbal Instrumentation”. The Sonnet to Wagner likewise demonstrates his attempts to apply it: here the weave, elsewhere purely melodic, becomes harmonic, and through deploying words for their emotive value as vocal timbres, he achieves a magnificent and arresting effect. — Small wonder that his impressionable, receptive temperament should remain alive to fresh discoveries, especially ones so readily adaptable to his art… Shortly before his death, Camille Mauclair informs us, Mallarmé was labouring to complete Hérodiade. He doesn’t specify how or in what respect he was reworking it. Yet as early as 1887, the Master had spoken to me of this undertaking, which then required the composition of a Prelude and Finale. The Prelude — he read me perhaps sixty lines of it. These were symphonically conceived, following his “instrumental” theory — hence his sharing them with me.

Did he persist with this method? Surely not, for this Prelude, possibly unfinished, never saw the light of day. No one after me appears to have known it. As for the “Finale” — which would be, if you like, the Poem of Saint John, written much later and appended to Hérodiade — it is purely in the established Mallarméan manner. I believe he destroyed that experiment out of some understandable pique against Scientific Poetry. A clue to this resentment might be found in Divagations where, discussing various techniques, he passes over in silence the very one that came first chronologically and in general influence, as we have seen: Verbal Instrumentation itself…

In L’Art en silence, Mauclair maintains that “the method of allusion, allegory, fiction struck Mallarmé as the only logical approach.” We have identified this as his art’s defining feature. Yet beyond all Symbolism, this method yields as its natural consequence a universal power of “suggestion”: an art of evocation that supplants — so relentlessly did he pursue it —narration, description and rhetoric. From now on, anyone who cannot instinctively evoke or suggest rather than state and display is no poet.

In this power — which all great poets have wielded, though none concentrated its forces as he did — in this above all, an immense legacy that guarantees Mallarmé’s work, however slender, will prove a wellspring of instruction for each rising generation of poets, lies an influence that has been absolute, we must emphasise, quite apart from Symbolism itself…

Regrettably, this art consecrated to Symbol — the poet of the late works (the Prose pour des Esseintes, most of the Sonnets, and Un Coup de Dés) failed to deploy it on any grand scale, or even in the service of ideas… If, as Mauclair also claims, the manifold Drama of Mallarmé’s dreams was to stage “the confrontation between conscious humanity and nature”, not the faintest realisation emerges. From the Prose pour des Esseintes onwards, offered as the ultimate manner, what do we find everywhere, as we have documented? Games of allusion to the most trivial realities, where “the idea”, if we can call it that, becomes mere satisfaction at conjuring up some object (chest of drawers, curtain, vase or guitar) without naming it! Games, alas, that resurrect the art of the Rhétoriqueurs…

Meanwhile the analogies spawning images grow ever more tenuous, ever more remote from one another. He proceeds through incessant ellipses, amplified, ruthlessly eliminating transitions. Thus between stanzas, then between phrases, virtually all connective tissue is severed. He drives his very strengths beyond not merely dangerous but fatal extremes, sacrificing them to the grammatical, to that verbal Absolute which obsesses him… Here lies “Mallarmé’s obscurity”: not in the ideas, which are simple, even simplistic, at times virtually absent. But might not this itself constitute a second source of opacity: that one struggles to discover something more, when there is so little? “The language of a dialectician”, Mauclair offers by way of excuse. True enough, for his final writings. The fixation of an impassioned grammarian who lost all sense of proportion, dizzy with the pursuit of the Word in its very essence, whilst ever more determined to “eliminate clichés, forge a unique mould for each sentence and practise purism”, as he himself declares in Divagations.

“Towards the end of his life,” Mauclair tells us, “he attempted what might be called a compromise between verse and prose, publishing an example of this experiment (Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard). It was an attempt to replace punctuation through variations in typeface — larger or smaller characters according to the relative importance of each phrase.” And there we have the supreme preoccupation! As for the meaning, the underlying idea of this experiment, Mauclair declines to determine it — as do Mockel and their contemporaries. More remarkably still, whilst Mauclair sees it as a compromise between verse and prose, Gustave Kahn maintains these are “free verse” and that his influence was instrumental in this late conversion of Mallarmé, whose entire oeuvre had been built on classical technique, who conceived each line as a single, solid “word,” and who confessed to us his instinctive repugnance at breaking caesuras in any but the traditional manner.

The principal concern that Mauclair identifies — expressing the weight of phrases through varying typeface sizes — merely betrays that Mallarmé had by then fixed his sights exclusively on experiments in Form which, when examined closely, appear to deny the intrinsic value of both word and thought. We should remember: “The Symbolist Movement is a movement of Form, rather than ideas.” (Art en Silence.)

I know — oh yes, I know — the torment of desire, the consuming anguish to render in writing the whole of our understanding, all the complex vibrations of things — not simply that words should stand as signs representing the mind’s energy and labour, but that they should become a living substance, an act in themselves! I too have sought to make the Word express thought through every artistic mode it might embody or replace; sought to make it express at once the idea in its fullest conscious reach and the very process of those manifold sensations that give birth to both Idea and Emotion— in living, universal Synthesis.

Yet we must learn to relinquish our work when we feel within us the despair of impossibility. The word, however intimately we sense and probe it, however close we come to its psycho-physical origins, the word is not of the same essence as thought. It remains somehow more material, thought’s instrument, forever inadequate to its task…

For failing to grasp this; for sublimating the sense of the word to excess (the very sign, indeed, he sought to abolish); for pruning from his syntax too many connective threads of discourse, leaving phrases naked in their abstract barrenness, — Mallarmé fell, hallucinated by Form alone, its sacred victim, yet a perilous example… No matter. It is precisely this consuming preoccupation that allows us to call him the quintessential Latin, an author of purest French tradition. True enough. He pursued one entire dimension of Poetry to its furthest reaches. He drove to the ultimate boundary that irresistible preoccupation of so many: the preoccupation with “Form” — the very foundation of “Symbolism.”

(Again excepting certain members of this School whom we shall consider, Francis Viélé-Griffin above all.)

“Yet,” Mauclair concedes, “Mallarmé published almost nothing that conformed to his System. Those occasional sonnets he offered up were merely trials.” But the principles of this “System” Mauclair invokes would be found within the collected pieces of Divagations, and in what he tells us of Mallarmé’s envisioned Work: a grand, manifold Drama, sacred in the modern manner, wedding mime, dance, music, and dramatic verse. Let us then briefly consider what this artistic vision might have entailed, drawing too on my personal recollections from before Mallarmé had absorbed those external artistic impulses whose traces surface in Divagations, and without, as I say, all those philosophical intentions that Camille Mauclair, Albert Mockel and their followers attribute to him, as though driven by an almost unconscious need to furnish Symbolist Idealism with some constructive principle it assuredly lacked.

But I must insist: it is false to claim Mallarmé never applied his system. Setting aside that unrealised Work, barely even dreamt, his thought both is and is nothing other than “Symbolism” itself. And whatever his wanderings into error, therein lies his enduring and precious glory…

The Dream Work

We have seen Stéphane Mallarmé’s poetic evolution first answerable to principle, then, in striving to surpass itself, to artistic achievements that came to him from without. Later, we observed his attention to “verbal instrumentation”, attested by sonnets and passages from Divagations, where the word “instrumentation” repeatedly appears in the literary sense I gave it.

The artistic mode and the thought — or rather the mode of thinking — that constitute the Symbolist concept gradually crystallised as they condensed into poems of ever-diminishing scope, finally into the sonnet alone. Games of analogy rendered through images increasingly purified of all concrete substance, expressing an idea stripped of every sign, whose simplicity often bewilders, whilst the art that evokes it, that suggests it, displays an ever more astonishing subtlety. This Symbolist manner, henceforth mastered, we can date from the sonnet Tombeau d’Edgar Poe (1877), which reads like an intensified version of the Toast Funèbre à Théophile Gautier (1873).

Yet nowhere in the work, whether earlier or later, does one discover any thread of overarching thought linking the various poems and sonnets, any revealing sign that might suggest this secret work the Master promised us and on which he was meant to be labouring. “One must attribute his meagre production to two causes,” wrote the Italian critic Vittorio Pica in a comprehensive study: “the first being that he works continuously on a poetic drama intended as the supreme incarnation of his artistic will” (Revue Indépendante, March 1891). It is abundantly clear that not a single page of his published poetry relates to this Work itself.

We must therefore speak of it by gathering the little he told me directly, and what he shared with select others at his Tuesday-evening gatherings. I shall recount certain indications I retained which others have neither known nor recalled:

The Work, it seems, was to comprise twenty volumes. Four, presenting the generative propositions of the series, were to be strictly interwoven, forming the radiating centre of his thought. Each of these four books would generate four others directly derived from it. The whole would constitute a philosophy of the World. Yet he revealed to me (in ’87) only the governing Idea of a single book amongst the four: “Were I not, nothing would be.” Mallarmé offered me no details of composition or substance.

Nothing personal, then. We have grounds to believe that this Work, had it been constructed and written, would have embodied in its philosophical essence an idealism wherein the Self incarnates the creative Idea of the World — where one would rediscover Platon, Fichte, Hegel, Schelling.

Vittorio Pica, Mauclair, Mockel, and others following their lead, have spoken of a poetic drama. Was a Drama meant to crown the work as synthesis? Or did it unfold, in Mallarmé’s conception, through all twenty volumes of the plan? Impossible to say, since he himself kept silent. The Work — let us grant this for the entirety — was therefore to express itself, piece by piece, through Theatre as well as Book. Here are further indications of how Mallarmé intended to arrange the volumes:

The volume would be a duodecimo, and the paper’s folding would participate in expressing the thought. The book being virgin, uncut, the reader would know only those pages visible along the volume’s edge. From this first reading he would grasp the “exoteric meaning” of the work. Thus initiated, he could then cut the previously inviolate pages where he would discover the “esoteric meaning” — complete at last! (I have said that Mallarmé possesses genius, but also an ingenuity and propensity for paradox that spoil it. Here’s a singular example. For my part, this necessity of specific folding applied to the expression of thought cast the gravest doubts on the grandeur of the promised Work. Just as the perpetual promising of it later vexed me, and equally vexed Viélé-Griffin— as Ernest Raynaud observes with considerable malice.)

Perhaps Mauclair attempts to soften this eccentricity when he writes, himself quite the dialectician: “By book, Mallarmé understood, like Edgar Poe, a condensation of restricted thought and emotion, a sort of spiritual vade mecum, dazzling, profound and brief, whose highly concentrated symbolism would contain a series of meditative themes upon which the reader’s personal labour might exercise itself” (L’Art en silence, 1901). If we decode this, following indeed Mallarmé’s own frequently half-admitted thinking, it claims that each reader can and should extract from the same reading whatever meaning personally suits him, even according to the particular mood of the moment.

But did Mauclair also recall that evening when Mallarmé, protesting that the Book remained too explicit for the “dazzling, profound and brief” effect, dreamt of a “sort of watch whose face would bear simple signs variously disposed and coloured”? A watch which, drawn from the pocket, would speak sufficiently through these signs — moveable and manipulable in diverse ways — to instantly suggest an entire meditation on man and universe, according to the whim of the “Self” bearing this precious little instrument. A prayer wheel of quite another order!

Since we are exhausting all intelligence about the dream Work (whose dream scarcely shows more coherence than most dreams do), let me recall from my own memory this further detail: the nature of one Character who was to appear on stage at a solemn moment. A character would appear, hieratic, beardless, wholly swathed in precious white cloth, without gesture — upon his head the papal tiara, domed and equally white, girt with three crowns studded with all manner of gems. This supreme Pontiff would be a Phallic symbol, around whom would doubtless revolve, as Mallarmé envisioned, the ritual dancers.

I fear, alas, that from the Crowd — that ideal Crowd “which suddenly needs,” he writes, “to find itself face to face with the Ineffable or the Pure, poetry without words” — would have erupted laughter and catcalls rather less pure, and decidedly ineffable! Words, images, beneath which lies nothing. And as for the Representation, of which one character has thus been presented to us, nothing but allegorical facades where we encounter the analogical method once more, without grasping any emergence of a new idea, grand and universally stirring…

Yet surely we cannot fail to notice the glaring disproportion between this vast blueprint for a work of deliberate philosophical complexity, and an artistic manner so desiccated that it barely harbours an idea — where idea itself becomes no more than a pretext for chasing after verbal expression, for the Word’s own sake, driven to find satisfaction in itself alone? Where, in the ultimate contradiction, he would deny all value not merely to the Idea but to the Word itself when, in Un Coup de dés, he contrives to distinguish them through typographical arrangements that pillage every last case in the printer’s composing room.

This disproportion, this contradiction, cannot be gainsaid. The truth is that the galvanising impulse towards such a work came to Mallarmé, quite clearly, from Wagner’s vigorous genius. Perhaps from his Parnassian days he had retained an early fascination with Wagnerian thought. After all, wasn’t Mendès his first and most fervent champion in France? (From that period, too, he must surely have embraced the Hegelian idealism that Villiers de l’Isle-Adam was then expounding.) But the decisive Wagnerian intervention came around 1885: the orchestras resounded imperiously with Wagner, and scarcely a concert passed without Mallarmé in meditative attendance.

That secret cabinet of which we have spoken did exist beforehand, true enough, receiving those slips of paper on which Mallarmé would jot down, at all hours, thoughts that came to him as he prepared his great Work. But we might well ask: was his conception the same before 1885-86 and the years that followed? I am tempted to think that only then, listening to Wagner’s music ad nauseam and penetrating ever deeper into it, did he develop his vision of a grand Poetic Drama, a new Tetralogy. The way he spoke of it — he had clearly seen his own work through the lens of Wagner’s achievement. Indeed, it’s from 1886 onwards that he speaks of it most frequently, though never becoming explicit, as though he were still working through the details in his mind. In August 1885, the Revue Wagnérienne published his telling article: Richard Wagner — a superb meditation by a poet who receives an inspiration which he simultaneously interrogates and refashions…

If we now consider what Mauclair has faithfully recorded of Mallarmé’s own words regarding his theatrical work and its Symbolisation, we discover that the poet’s dream unfolds as a literary variation on the stately architecture of Wagnerian Drama.

The Fusion of word, gesture, décor, Ballet, and musical expression was absolutely essential. Verse constituted the elocutionary mode of the thinking individual, of Man: through verse the drama’s ideas found their voice. And since every idea represents a glimpse of the divine and is therefore religious in essence, Verse expressed it, musical and rhythmical.

“The Symphony embodied the passionate, sensuous element. Gesture, through the art of mime, provided the active element… Ballet formed the living element of the décor. It represented whatever in nature participated in the individual’s emotions — whether massed at the rear of the stage, seeming to incarnate the setting itself, or whether, by detaching one or several Ballerinas, the poet envisioned them as sensations flitting about the protagonist.

“Thus, as Man articulated an idea, the Mime would execute the gesture his words commanded, the Ballet would intervene to express the consequences of these acts in nature, whilst the music conveyed the drama’s overarching emotions — rather like the role of the Greek chorus. The verse’s tonality and rhythm — the central element — would govern both orchestra and recitatives.”

Here we have the very staging of Wagnerian drama, save that the predominant role falls to the individual character. The other, crucial difference — where Mallarmé stakes his claim to originality — is his rejection of any pre-existing Legend: he would forge his own themes, literary and ideological, reaching towards grand Symbolic universals.

“Between the hero and nature bearing witness to his thoughts, the Ballet would move back and forth in perpetual exchange. Everything in the theatre, said Mallarmé, operates through reciprocities, always in relation to a single Figure.” — The Dancer held paramount importance in the Symbolist Master’s conception: he returns to her again and again. For him, she is no mere human body in motion but rather a metaphor: sword, cup, flower — a corporeal script, signs and images, hieroglyphs brought to life…

Examining these theatrical propositions closely — theatrical only, mind you, for generative ideas are nowhere in evidence— we find assembled the various strands of Western legendary Theatre, both Greek and Wagnerian, with an overriding emphasis on Symbolic necessity: that evocation and suggestion which constitute Mallarmé’s distinctive art. Furthermore, and most fundamentally I believe, he was haunted by the stirring ceremonial of Catholic worship (having no knowledge, for instance, of the far more sophisticated religious representations in Tibetan temples) — worship as it unfolded beneath the luminous stained glass of our cathedrals when, in the Middle Ages, the Soul of the Multitude communed with the soul of the Celebrant, and when, through antiphonal responses to the priest’s words at the altar, there arose between them an enthralling, mystical dialogue… On this theme, despite his convoluted prose, there are two or three pages of magnificent suggestive power in his volume Divagations. Clearly, the central Figure of Mallarmé’s drama, Man, is the priest who answers for the Divine, effecting through the Divine the union of the Multitude. Mallarmé’s theatrical art aspired to celebrate intellectual Vespers of universal thought…

Yet what we have here is merely an incomplete, fragmentary description — magnificent in places, yes — but only of the Drama’s outward shell. What new themes, capable of universal resonance, should spring from this complex and simultaneous Figuration to forge a new communion? The poet never said. These themes were to belong to no time, no place, to correspond with nothing in existence — not even legendary figures. They must, then, have been philosophical: broad states of soul and universal emotions rendered in Symbol. “Spiritual fact,” Mallarmé calls it, with that infuriating brevity he adopts whenever these questions arise — questions surely unresolved in his own mind. And these Symbols, he tells us further, “must synthesise nothing but those delicate magnificences, immortal and innate, that exist unbeknownst to everyone in the gathering of a mute assembly.” But what, precisely, are they?

We glimpse, then, that his principal Hero remains the Self — of all assisting “selves” rendered synthetic. I have cited Mauclair’s crystallising phrase: “Confrontation of the conscious human being with nature” — though whether these are Mallarmé’s own words remains unclear. Since this might appear allied to certain of my propositions, and since clarity matters, we should parse it in Mallarmé’s sense.

Mallarmé could never have meant this as I do, in evolutionist terms — not he who couldn’t dispense with Eden. He doesn’t suggest that Man, made conscious through Science’s gift of deeper emotional knowledge of universal relations, recreates within himself this Universe now conscious and self-aware in his brain. Not at all. Rather, the “Self,” conscious through introspection of “immortal and innate” ideas, recalls these and draws them inward, away from the world of material appearances — which are mere Symbols. Any themes Mallarmé might have conceived would thus have been bound up (as the single one he mentioned reveals) with Platonic thought — the archetype underlying all things. Here is that fateful concept, so fortunate in its destiny through Greek philosophy and thence through Western speculation, drawn from the ancient Indian system of the philosopher Vyasa, whilst the powerful doctrine of his antagonist Kapila, whom we might call “evolutionist,” appears only among the Ionians who grasped the mutability of things, and has been vindicated only yesterday, still furtively attacked or corrupted.

So we know nothing definite about the inner thought of this “dreamed Work.” If he amassed materials, he never built; he never even showed us the blueprint. He gave us the permanent actors of his drama, not what they were to express. This poet, whom some would have us believe realised the Idea in its essence, remains stubbornly silent about ideas themselves. As far as we can tell, his philosophical thought brought nothing personal, nothing fresh. His scenic dream, though, springs from Wagner’s colossal aesthetic. And the secret of this Work’s non-creation — this haunting we might still call magnificently chimerical — is that the influence working upon Mallarmé here accorded neither with his temperament nor with his aesthetic, which, though matchless in suggestion and in the art of Symbol, achieves these only through subtlety. Nothing in him is colossal or overarching, nothing speaks of a mind built for Synthesis.

I have maintained that not a single page in his scattered œuvre bears on this great Work. Albert Mockel’s claim that “His poems remain like dispersed statues marking where the grand edifice should stand” is mere wordplay. As is his comment on that final poem, Un coup de dés. How reckless to present this “hermetic and fascinating” poem as “the surprising trial of a method whose resources and drawbacks the poet had not yet fathomed” — a method intended (rather belatedly) to express the dreamed Work.

The “throw of the dice” poem, Mallarmé’s last illusory pursuit of absolute Form — where form eclipses all idea — exposes for me precisely this painful gap between his grand vision and his poetic technique, suited mainly to fragmentary inspiration, egotistic and fortuitous, from which he never broke free.

I think it dangerous for Mallarmé — indeed potentially damaging — to credit him with grandeurs he lacks when he possesses others that will endure. “He fused individualism with Mysticism,” writes Camille Mauclair. “Very few have taken this path.” I believe the opposite: most have pursued this egotistic poetry, this poetry of the “Self” exalted as anthropocentric norm, as measure of the Universe. John Charpentier rightly sees in Mallarmé “merely a slender offshoot of the great Baudelairean trunk,” just as Gustave Kahn rightly considers Symbolism the supreme culmination of Romanticism and Parnassianism.

To build upon the vaporous dream of a stillborn Work, to ignore the profoundly fragmentary nature of what was published — its lack of unity, its subjection to successive external influences — is to push admiration beyond its proper bounds and risk undermining it, as when someone declares of Mallarmé: “He possesses the character of the System-builder, fusing pure with practical reason, moving with equal ease through abstraction and through life without losing himself in either.” The work itself rebuts this verdict. He lacks the builder’s character — for this simple reason: the intellectual architect, in his smallest productions, inevitably returns to unity, because Fragments, through their evocation and suggestion of relationships, necessarily connect to a whole. Fragments, however scattered, will embody this Unity, both individually and collectively. There lies the hallmark of the architect’s genius.

I find myself, then, drawn to the measured though undeniably admiring judgement that G. Walch delivers in his Anthologie des Poètes Français, when his scrupulous impartiality declares, as if with reluctance: “Yet one must face the fact that Stéphane Mallarmé, despite cherishing to his dying day the ambition of writing his dreamt masterpiece, published nothing, wrote nothing — indeed, so far as anyone knows, sketched nothing — that bore upon it or might offer the slightest glimpse of its nature. Despite this apparent failure by the head of the Symbolist School, one can only admire his noble endeavour to ‘consecrate poetry, to establish for it once and for all a higher calling, beyond the shortcomings and half-measures of prose,’ beyond the crude precision of mere words, and to forge a language of superhuman essence that would enable at least the elect to commune with the gods through the medium of the universal Symbol.”

Here the Anthologie‘s author admiringly acknowledges both the supreme consecration of the Symbolist way of thinking and Mallarmé’s dazzling exertions towards the quintessence of the Word — which is why, whilst acknowledging the “failure,” we must forgive it with regret, and might indeed call it only apparent… But I would go further. It strikes me that a poetic theatre worthy of French Thought — rising above the abominable degradation of today’s stage — might well draw its rebirth from specific elements of this dreamt Work’s theatrical preoccupations. I know contemporary poets who have gathered from this diffuse Reverie — which could never assume definite shape for want of a unifying idea — if not inspiration proper, then at least confirmation of their artistic convictions. They too hold essential the subtle, nuanced interplay of music accompanying evocative dances and the chorus’s collective voice — all surrounding the Action which they seek, in the timeless manner of Aeschylus, to shape into human and newly sacred Syntheses, charged with the emotion of knowledge and that universal sense which binds us across time and space… Yet within the Symbolist School — beholden as it was to both romanticism and realism, whilst engaging with life and pursuing speculations on human destiny, drawing nearer to us through its architectural ambitions — surely Paul-Napoléon Roinard emerges as one who brought Mallarmé’s dramatic vision partly to life? The great-souled poet of powerful utterance who gave us Le Miroir and Tous les Amours, possessing both a robust grasp of reality and the gift for transforming it into spiritual transmutations (as his Flaubertian bearing attests), understood what was worth preserving in Mallarmé’s diffused vision. He claimed this inheritance whilst quite naturally transcending the Symbolist mode’s excessive refinement and narrowness to bring it to fruition. Through a modern lens, Roinard has recovered and remade the ancient art of Allegory. A Naturist and philosopher who works the human material with profound sociological feeling, he looks beyond retrograde movements to perceive the eternal forces of love and becoming: and this Allegory —no mere verbal display — he has made richly complex, embracing “all the loves” within the drama of heart and intellect. Intellect especially: for in Roinard, as in Abel Pelletier, author of Titane, we discover the same lofty purpose, recognised as vitally essential: to raise thought and thought’s champions to the supreme heights of human achievement… Moreover, by anchoring his Work in Matter’s still-hidden powers, he expands it into a Universal that throbs with Mystery, wherein the emotion that both knows and divines finds its focus. Paul Roinard’s Work therefore commands our particular tribute, as does his literary life, devoted with uncompromising passion to his art…

…Yes, whatever Mauclair may claim — he who has so often credited Mallarmé with far too much — Mallarmé does not move within Life (nor does Symbolism, and this is precisely why Tomorrow, carried forward by evolution, will admire them only by looking back). He has indeed ‘moved within Abstraction’ — that much is true. But it is in the realm of the Word that he has ventured further than almost anyone has dared. Following Baudelaire’s lead, his innovation in Syntax stands as his capital achievement… ‘Syntactic innovation is exceedingly rare,’ Camille Mauclair observes; ‘it sets a writer apart like nothing else.’

Mallarmé’s most distinctive originality lies, then, neither in the rare epithet nor in Rhythm — which he generally keeps within strict classical bounds — but rather in how he arranges the elements of discourse. His is an intricate, complex design where word placement corresponds, with utmost subtlety and method, to the coordination of every nuance in the artist’s will as it works through sequences of images. Beyond this textural science, the very sound of words in their positions — even deliberately jarring where he chooses — adds to their meaning an emotional charge that arrives suddenly, almost inexplicably. True, these are qualities found in every genuine poet of stature; yet through his particular intensities, intentions, and insistent repetitions, Mallarmé has brought such qualities to their apex in the quest for expression.

He has rightly been called a ‘grammarian of genius’. The Word dominates and drives him forward, increasingly overwhelming both emotion and idea, destroying all spontaneity. Synthetic in this particular sense, he pushes ellipsis to its limits, eliding the connections between stanzas and sentences — as though ideas should indeed emerge from the gaps themselves! He has eliminated virtually every transitional phrase. With the rarefied pleasure of an ultimate initiate — rather like Plato, Apollodorus, or Aristotle — we watch him refine every mode of discourse: sudden transpositions that throw periods off balance; words deployed simultaneously in their literal and figurative senses, their material and spiritual meanings; attributes attached from afar to unexpected terms, defying grammatical logic; metaphorical applications of every kind. ‘Joy of being unburdened!’ — such is the principle animating his song… This supreme game of dismantling discourse brings about an astonishing decomposition of ideas, reducing them to spiritual particles which the perilous Logician will reassemble according to his artistic design!

These are ideas he chooses to ‘guide the meaning of images’, as Albert Mockel puts it, though he adds with apparent unease: ‘This rather imposes meaning upon them from the outset.’ (Albert Mockel: Stéphane Mallarmé). Nothing could be more accurate than to say, judging by Mallarmé’s entire œuvre and his statements, that this a priori determination of ideas meant to ‘guide the meaning of images’ — which matter more to him than the ideas themselves — constitutes both his art and his philosophy. Thus, as we have seen, he remains within the sphere of egotistic Poetry, within that spiritualism which finds in the World only the meaning that resides in the immaculate ‘Self’, itself part of the Idea that produced it…

Stéphane Mallarmé stands as a magnificent closing Figure. Of Symbolism — which has animated nearly all poetry since ancient times, when it first concealed forbidden Knowledge and its attendant emotion beneath the Symbol — Mallarmé represents the ultimate refinement. Of Poetry driven by egotistic inspiration (whether determined by individual emotion and sentiment, or by the individual’s appropriation of general ideas now become commonplace), and philosophically speaking, of the ‘Self’ extending itself by fashioning the World after its own emotional images — Mallarmé represents the most thoroughly intellectualised expression, yet one that sterilises, that loses the Idea in verbal expression for which the idea becomes little more than pretext. The Self becomes the Idea, the Idea becomes the Word — is nothing but Word, cerebralised to a point of impossibility turned mystical…

Having studied him thus, with all my conscious thought and admiration for his noble achievement — not merely as the creator of ‘Symbolism’ but as a vital force throughout an era’s Poetry, through his decisive mastery of evocation and suggestion, and his role in syntactic evolution — Stéphane Mallarmé rises before us, I repeat, as a magnificent and singular Figure, even if a terminal one.

I have deliberately restored to their proper truth and value those Facts too often distorted by interpreters’ own imagination and thought, by their unconscious or self-interested borrowings from rival theories, and by the rash suppositions and conclusions (contradicted by the poet’s actual work) that have arisen from knowing too little about the Work that never was. I have thereby shown that we are dealing neither with a constructive mind capable of true Synthesis, nor indeed with a genuine creator, for we have seen his evolution decisively shaped by external forces and influences on at least two crucial occasions… Though grounded in the actual Work, my conclusion remains nonetheless suffused with its splendid Beauty and inscribes Mallarmé’s name amongst those predestined Poets whose existence stands as historical necessity.

This is one of 50+ rare French literary texts translated into English for the first time on this site.