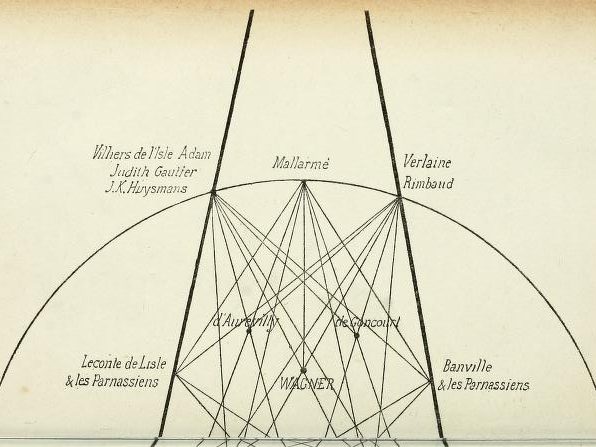

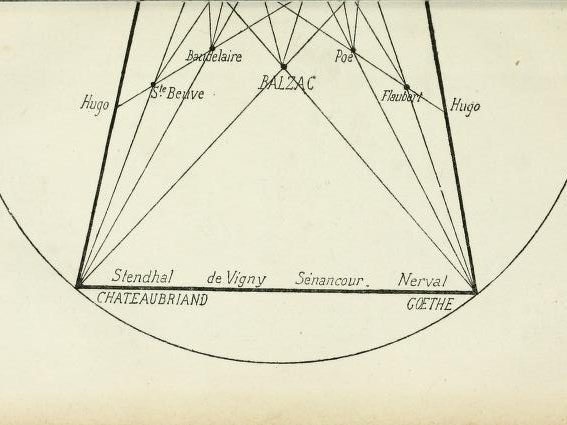

Summary — Chateaubriand and Goethe. — Stendhal, Vigny, Senancour, Nerval. — Hugo. — Balzac; Wagner. — Poe; Baudelaire. — Flaubert; Sainte-Beuve. — Leconte de Lisle; Banville and the Parnassians. — Goncourt; Barbey d’Aurevilly. — Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Verlaine, Judith Gautier, Huysmans, Rimbaud, Mallarmé.

As the brief Romantic and Naturalist periods unfolded in the wake of the exhaustion that came with the long Classical age, certain poets—most of whom found themselves swept up in one or other of these latter movements—discovered, or more vaguely sensed, an aesthetic ideal more complete than any school could offer: more distant, free from the plodding constraints of analysis, at once broader and more penetrating, claiming for itself a universal domain where it might pursue the Absolute. Not one of these Poets—supreme though they be—whom I shall now discuss with reverent joy, awakens in us that perfect, consummated admiration we long for. In none does that genius blaze forth of which Edgar Poe speaks, “resulting from mental powers equally distributed, arranged in absolute proportion, such that no faculty enjoys undue dominance.” No doubt such genius will forever refuse to manifest itself, lest it discourage posterity. Yet all these poets possess illuminations unknown before their time. Their half-open books reveal new paths to those who can truly read, paths of infinite vista. Nothing written hereafter will be new without owing these masters its grateful homage.

Chateaubriand and Goethe stand at the wellsprings of modernity, marking the base angles of a great spiritual triangle whose apex disappears into the infinite. In them the mystical spirit and the scientific spirit—both deeply sensual, though in strikingly different ways—collect themselves and achieve self-awareness. They stand worlds apart, occupying the outermost boundaries of human thought. Yet through their mutual exchange of aesthetic sensuality, they herald that profound, that urgent contemporary yearning of the human spirit: to unite the mystical and scientific currents into one broad, living stream where Beauty meets Truth in Joy. One might have expected the scientific to swallow the mystical whole. Recently, Science had crossed out the word Mystery. With the same stroke, it had eliminated Beauty, Truth, Joy, Humanity. Naturalism bore this out completely, offering us its dreary, vapid brutes, certainly devoid of mystery. Therein lies the problem: they lack in truth precisely to the degree they lack in mystery. The deleted words have re-emerged beneath the erasure: the ink was inferior. In the sphere of Art, their principal battlefield, Mysticism has reclaimed from encroaching, grasping Science not merely what had been stolen, but perhaps something of the domain held by Science besides. The backlash against scientific literature and its insolent and desolating negations has manifested itself not as a grand surge towards joyful Beauty, but rather through a revival of psychological studies that barely acknowledge the organism whilst remaining beholden to science on one hand, and through an unexpected poetic restoration of Catholicism on the other. Three among the greatest Poets of our age—Barbey d’Aurevilly, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, and Paul Verlaine—are Catholics. Yet their Catholicism, which Catholic and Roman priests greet with hostility rather than mere indifference, bears every mark of a profound return to Origins. These Catholics may well have heeded Goethe’s great word. Taine, having catalogued the inadequate responses the past offers in pursuit of answers to modernity and its challenges, observes:

“Do these even qualify as answers? What do they propose but satiation, stupefaction, deflection, oblivion? Another response exists, more profound, which Goethe first articulated, which we begin to suspect, towards which all the labour and experience of the century converge, and which may well form the substance of literature to come: ENDEAVOUR TO UNDERSTAND YOURSELF AND TO UNDERSTAND THINGS.”

These Catholics may have encountered Catholicism at its zenith of splendour and truth whilst returning to the living sources of the past. Its vanished beauties seduced them, and they have brought them back to life. Yet with the actual religion (which is false) that lives (though dead), they form an anachronism that horrifies it. The day a Pope ordered draperies painted over the nudes in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement marked the death of Christian art. Contemporary Christianity invariably assumes Tartuffe’s posture when confronted with the audacities of these Poets who profess to serve it whilst possessing genius! Hence, they belong not to this Church. They have caught up with and overtaken Chateaubriand. Their faith bears the unpolished lustre of an ancient artefact whose brilliance lay preserved beneath dust: theirs is a rediscovered faith. It serves as pretext more than reason for achieving mystical certainty, though one says this without questioning their obvious sincerity. The mystical spirit exacts revenge upon the scientific spirit that humiliated it by arresting at one of humanity’s oldest and simplest “explanations of man and things” some of the world’s finest minds, who were suffocating in the airless chamber of science alone, science that neither respects nor comprehends Mystery, and who sought refuge in antiquity and its spacious epochs where the spirit could breathe… What mattered was that the word Mystery be spoken again. Far from preventing us from hearing Goethe’s answer, it reinforces it. The sense of Mystery awakens and sustains our passion for Causes. In this grand dialogue of modern thought, Chateaubriand and Faust, Goethe and Le Génie du Christianisme can find common ground. They converse on the heights, their voices disturbing the same rarefied air. One day their words will fuse into a single magnificent Logos.

Stendhal, Vigny, Senancour, Gérard de Nerval… What shared thread, one might ask, binds these poets together? They share but one trait: they wrote, roughly speaking, between 1820 and 1840, for generations that would read them circa 1880. Le Rouge et le Noir, Les Destinées, Obermann, Le Rêve et la Vie—our sacred texts! Books ignored at birth.

In Stendhal we encounter a constructive mind, sharp, nervous, an unerring psychologist, utterly modern, nearly indifferent to formal beauty, attuned to the soul’s expression, to physiognomy, blessed above all others with an intimate grasp of life—a grasp he possessed only with pen in hand, inventing truth with astounding certainty. His pen was a divining rod, the talisman that reveals buried treasure. There exist such men, Balzac and Stendhal for instance, who comprehend life before living it. Their souls are microcosms wherein they need but look to see the world entire. Perhaps they never truly live at all. When roused from their dreams, they pursue only trivial or outsized preoccupations—Stendhal chasing worldly triumphs that slip through his fingers, Balzac launching vast commercial ventures that overwhelm him. Yet these very minds that life makes fools of, once restored to their poetic element, grasp and lay bare life’s most hidden workings. One teaches the art of securing victories he never won; the other conjures businessmen whose faces startle with their truth, initiating us into the vast daily machinery of commerce and banking. For others, whose inner realm enchants and consoles them for existing, “Life itself is the dream49.” For Stendhal, his dream is life. The concept of passion, more than passion itself, enthrals him. He is a great intelligence in the grip of passion.

Alfred de Vigny: a Raphael painted in shadow, a recluse, a soul at once proud, tender, and wounded—a true Poet.

Forever engaged in silent colloquy with himself on humanity’s gravest concerns, he rarely breaks his silence except to write—with a kind of bitter, fierce joy—one of those sombre, pristine pages: La Mort du Loup, La Maison du Berger, Le Jardin des Oliviers. This joy isn’t despair wrapped in cruel irony. Rather, the Poet draws from his unblemished pride and conscious honour the will to live and capacity to love. These works are trembling protests, rebellions more profound than any of Manfred’s, against the injustice of the God who would have ordained the conditions imposed upon our lives.

S’il est vrai qu’au jardin sacré des Écritures

Le Fils de l’Homme ait dit ce qu’on voit rapporté,

Muet, aveugle et sourd au cri des créatures,

Si le ciel nous laissa comme un monde avorté,

Le Juste opposera le dédain à l’absence

Et ne répondra plus que par un froid silence

Au silence éternel de la Divinité.

[If it be true that in Scripture’s holy ground

The Son of Man spoke words we see recorded,

Mute, blind, and deaf to every creature’s sound,

If heaven left us stillborn and aborted,

The Just shall meet absence with disdain

And answer only with cold silence

The eternal silence of the Divine domain.]

The austere tone, the restraint of this rebellion proclaims the rare qualities of the soul that ventures it—one passionate in conviction yet composed in its protest. Vigny descends from Pascal. Less mighty, less inspired, more concerned with external and emotional dimensions, Vigny has the same unflinching honesty as Pascal, and their meditations share a theme: Les Destinées. Some have deemed Vigny an atheist: he is no more so than Pascal. Pascal feels the Temple he champions collapsing beneath him. Vigny surveys the wreckage, pronounces it bereft of divine resonance—bereft at last!—and moves on. Yet like every Human worthy of the name, he seeks God. His boundless melancholy springs from living in an interregnum. His sorrow mirrors Musset’s, mirrors Senancour’s.

Qui de nous, qui de nous va devenir un Dieu!

[Who among us, who among us shall become a God!] 50

Each lacks a symbol of the Infinite answering their soul’s every yearning. Art—Beauty in itself—cannot yet stand alone, whilst the Gospel now speaks in a tongue long dead. Yet Vigny, perhaps unconsciously, strives with all his might to invest Art with its absolute mission. In Stello, Vigny depicts the rare atmosphere a Poet needs: he must be surrounded by those who know to treat him with reverence and thoughtful discretion. The verse of Les Destinées approaches modern verse itself. It trails only slightly behind the innovations of Sainte-Beuve and Baudelaire. Moreover, Vigny grasps the supreme vocation of the Poet, naming him “the late-coming conqueror.” He even intuits that this Poet’s true calling, his first and final duty, lies not in amassing beautiful ruins of chance, but in raising a monument51—and more remarkably still, that this Poet will create in full consciousness of his inspiration.

Sénancour52 embodies all the beautiful, piercing sorrows of the poet of his time.

He is not yet resigned to being less than a man, to letting himself, like Goethe, be branded with hypocrisy and egoism so as to raise, far from the frenzy stirred by passion, that monument Vigny spoke of. Sénancour, ever the genius adrift in solitude and doubt; a desolate genius caught between what the mind dreams and what the heart needs, satisfying neither, yet whose plaints and shadow-murmurs carry a raw sincerity I find more authentic than the shouts of many so-called living souls. The sickness of hope—how far his dreams outstrip his powers—here lies the chief source of Sénancour’s melancholy, and indeed of every sadness in his age. But there are others, and these two further causes constitute those aspects of his genius for which our own era might particularly cherish him. This man, who shuns civic duties and lives “wretched and almost ridiculous on a subjugated earth,” who speaks with strikingly immediate conviction of love’s natural freedom, possesses—like Shelley at the same moment—a less lyrical but more penetrating feel for a pantheistic poetry where man would not dissolve into nature but would become faithfully, truly her son and bear her likeness. This likeness Obermann discovers within himself, drawing from it a pride that places him inwardly beside man as he ought to be. He finds it in that instinct which, more than to anyone else, yields to him the meaning of natural things, above all flowers:

“The jonquil or jasmine alone would suffice to make me say that, such as we are, we might inhabit a better world.”

People say this Obermann, like all his contemporaries, read Rousseau and took from him both this revulsion from society and this love of nature. They forget, though, that both spring from an extraordinarily intense inner life, so intense that it perhaps yields, in its day, only to the dreadful meditation Balzac pursued without rest. Here is the second and nobler of the two personal sources I promised for Sénancour’s sadness: he never learnt to choose between the sentimental joy of action and the austere happiness of dwelling within oneself. Yet at least, failing to choose, he had the strength to point to the better path.

Gérard de Nerval—the wondrous mystery of that inner life!

In him this sense would at times grow so exalted as to shatter the equilibrium and harmony of the other senses, disturbing life itself. While they remain more intuited than proved, supreme gifts—gifts whose full flowering brings all elements of genius into balance and strength—unjustly monopolise the entire spirit: pierce it, intrigue it, threaten to corrupt it. Thus the same gift, belonging to Gérard de Nerval, produces Le Rêve et la Vie, — sublime passages in an incoherent work where the inner life, instead of governing the outer without merging with it, now annihilates it, now depraves it; whilst belonging to Balzac, it produces Louis Lambert and Séraphita, works of perfect poise. Yet Nerval’s intuition remains lucid. This perception—of two simultaneous existences dwelling within one soul—falters only when he either arrests its movement toward symbol or detaches it too sharply from the wholeness of ordinary experience. He shifts between direct and indirect approaches in an enervating hesitancy.

But what extraordinary pages! That madness—what astonishing intelligence of the invisible and unheard!

“…Everything in nature assumed new aspects, and secret voices issued from plant, tree, animals, the humblest insects, to warn and hearten me. My companions’ speech held mysterious turns whose sense I grasped. Objects without form or life submitted themselves to my mind’s calculations. From combinations of pebbles, patterns of angles, cracks and openings, leaf-cuttings, colours, scents and sounds, I saw emerge harmonies hitherto unknown. How, I asked myself, could I have existed so long outside nature without identifying myself with her? Everything lives, everything acts, everything corresponds. Magnetic rays emanating from myself or others traverse without obstacle the infinite chain of created things. A transparent web covers the world, whose delicate threads communicate, link by link, with planets and stars. Captive now upon earth, I commune with the choir of stars that partakes in my joys and sorrows.”

To this magnificent intuition of works where art would rest on metaphysics, Nerval adds both a feeling for legends and for the truly modern line: far nimbler than Vigny’s, far tauter than Lamartine’s, and infinitely more poetic than Hugo could achieve—authentic dream-verse of which Les Chimères provides brief, rare, but undeniable specimens.

I have just named Hugo. I have already observed that he is the storehouse of all formulae and stands at the brink of all intuitions. Yet as for concrete achievement, his work lies in ruins and his influence on the future will be virtually nil. Perhaps we shall, somewhat cramped by our hunger for the rare, the particular, the acute, profit from plunging again into Hugo’s inexhaustible torrent—but no one will seek his guidance anymore. He believed that by gathering into his hands the threads of the spiritual web stretching around him, he would erect the monument before which posterity would kneel. And behold, that monument has collapsed, leaving only some superb stretches of wall standing—things like L’Homme qui rit and Les Travailleurs de la mer (perhaps too literary, but flawlessly literary), admirable verses here and there (not one entire poem!), and scattered passages of prose53. Still, let us pay him substantial tribute: by legitimizing the freedoms his age knew it needed, he illuminated—in his own fine phrase—”the twilight of things to come,” stamping his name upon a decisive hour in modern evolution. Moreover, if he lacks direct rapport with the new generations, he affects them indirectly through their immediate masters, several of whom declare themselves his disciples, all of whom have felt the sway of ideas that, rightly or wrongly, are embodied in these syllables: Vic-tor Hu-go54.

I turn now to this century’s two genuine masters: Balzac and Wagner.

Honoré de Balzac invented the modern world and painted it with the thoughts of a modern man who vastly outstripped his hour. Without once copying, he achieved truth—that personal, superior Truth which seeks to clothe itself in Beauty. Accepting Madame Necker’s definition that “The novel must be the better world,” Balzac adds, “But the novel would be nothing if, within this august lie, it weren’t true in its details.” In its details, meaning in the deployment of elements that passion brings to life (“Passion is all humanity“), and in faithfully reproducing the neutral social surfaces, those conventional conditions of collective human existence. But Balzac animates these principles through his synthetic vision of the world’s unity of composition and society’s kinship with nature. By grounding a literary work on this scientific law of compositional unity, which represents the enduring and elemental law that governs nature, Balzac inaugurates authentic foundational Modern Art, whose essence is to return, through science, to original nature and proceed as she does. By distinguishing “truth in the details” (though this phrase may not capture Balzac in the entirety of his thought) from the “august lie” through which the novel must “aspire to the beautiful ideal,” Balzac inaugurates authentic formal Modern Art, whose essence is to bind with Fiction in an arabesque knot these weighty details of truth seized from nature or society through observation or intuition. Finally, far more clearly than Alfred de Vigny, Balzac grasps that the Poet mustn’t be left to the mercy of inspiration but must master it, that genius is precisely the deliberate capacity to be inspired, that genius thus ruled by a will itself ruled by reason must devote itself wholly to erecting a single monument, complete and unified55. The unity of Balzac’s monument is more contrived than genuine. No doubt it should have rested on ideas rather than characters. But Balzac’s chief failing—and I venture this criticism with full reverence for this omnipotent genius in whom we discern shadows only through his own reflected light—was this: though dissatisfied with the “Beautiful ideal” he invokes, he left the human soul as he found it, torn between Religion and Art already drifting apart, stretched between the Religion of the Cross and the joys of pure, unfettered Beauty. He who divined everything else failed to divine this: that Art doesn’t appeal to merely one part of the soul but claims it entirely, holding as it does the secret of everything, the power to fulfil every desire. Balzac would have grasped this truth had “truth in the details”—so revolutionary then—not commandeered his primary attention, diverting it from the “august lie.” Hence surely those flaws we lament in La Comédie Humaine‘s style and, occasionally, those slight deficiencies of thought. The world’s greatest mind courts countless perils if, in its artwork—an artwork that utterly transforms art itself—it doesn’t channel all its beliefs and dreams, all its loves and hatreds, all its hunger for happiness towards their natural end. This habit of awarding Christianity a certificate of social utility whilst actually dispensing with it in the work, recalls the strategy of the sacred ark used by Descartes. Fundamentally, Balzac’s true Religion is his Art, and what is truly True for him is what he discerns in humanity and strives to extract. One speaks convincingly only of what one believes. Had Balzac pressed through to pure fiction, he would have elevated his ideal of human truth into an Art-Religion. In works like Séraphita—sublime riposte to those who accused him of “regarding man as a finite creature”—he grazes this supreme realm, this promised land he won’t enter.

But isn’t he aware of this himself? I believe so. He knows what he lacks and perhaps views his magnificent achievement as the reality-foundations for the art envisioned for times to come, the artwork of dream! Isn’t this the meaning behind those strange words he inscribes to Madame Eveline de Hanska when dedicating Séraphita to her? He hopes this novel will be read only by minds “shielded from worldly trivialities by solitude. They would know how to impress upon it the melodious rhythm it lacks and which would have made it, in one of our poets’ hands, the glorious epic France still awaits.” And he asks that this book, which he seems to favour in his œuvre, be accepted from him “like one of those balustrades carved by some faith-filled artist, against which pilgrims lean to contemplate man’s end in quiet admiration of the church and its choir.” Here are unmistakable intimations of an aesthetic Absolute.

But Balzac doesn’t always own them. His preferred position is that of the sociologist: his agenda is to write the history of manners56, to “capture their hidden sense” and declare “how societies stray from or approach the eternal standard of the true and beautiful.” He went much further, and I believe he knew where his native genius was heading, where it would lead at least through its future influence. I believe I also detect a generous resignation resonating within his Work’s incomplete magnificence.

Richard Wagner accomplished two great things: he united all the art forms and synthesised observation and experience through Fiction. Today, none of his contemporaries—I mean those who think and speak sincerely—doubt any longer, after all the interested or merely foolish attacks that greeted his glorious endeavour, that along the path Wagner opened, at its very terminus, there stands resplendent the dazzling triumph of Art itself.

There seems little point in explaining how Wagner’s theatre, whatever certain critics have claimed, does not resurrect Greek drama57; how all the aesthetic resources the Master demands—music, stagecraft, poetry—serve the Action. These truths are well known to those for whom I write. Nor need we belabour the profound and weighty influence Wagnerian thought exerts—and will increasingly exert, so fruitfully!—upon minds committed to the luminous path.

What bears consideration is why this Thought does not itself constitute that triumphant gesture of which I spoke, the gesture that would bring everything to its conclusion (and which doubtless never will exist). Why this singular Work still leaves a gap between itself and the ultimate Goal? These are regrets and desires to whisper only in hushed tones, between two or three respectful yet independent souls—final regrets and desires which I nevertheless set down in print, secure in risking them without peril in our clamorous age when no one listens, confident they will prove harmless in this time when, as I have observed, silence has ceased to exist.

Three regrets, then.

First: union, not synthesis, of the art forms.

No single art dominates—and there’s the rub. Let us spare ourselves the hoary debate about which art takes precedence. Better to be decisive: the art that stands foremost is that which approaches most closely the source to which all must return—Thought itself. What stands nearest to thought is what speaks with greatest precision. This is manifestly Poetry. Yet precisely because it speaks with precision (even when it manages to cloak itself in enchantments—as the new Poets have shown, M. Paul Verlaine among them), Poetry may lack that essential Vagueness, the shimmering, translucent veil that Beauty requires. But if Poetry enlists the other arts to supply this vital atmospheric and emotional Vagueness, then let Poetry rule them! Otherwise, we have juxtaposition, perhaps union, but never synthesis or fusion.

Language forms the natural bond between spectator and spectacle, transforming the semblances of reality that listen into the realities of dream that speak. Language and Light together extend the theatrical experience from Stage to Auditorium, creating between the gesture seen and the faces watching an exchange of sympathy and emotion that flows back to nourish the very Gesture that sparked it. Let Language, therefore, permit Music to create the atmosphere in which the Word achieves its fullest significance, the way a sovereign prepares his route before setting out, not appearing immediately but sending his retinue ahead. Then, upon this prepared stage, let Language reveal itself in its true majesty.

Think about this: perhaps because he failed to give Poetry primacy over the other arts, Wagner felt compelled to eliminate that secondary drama played between Stage and Auditorium—a drama I sorely miss in this theatre where only the Stage receives illumination, as though to demonstrate through a device too crude and conventional (and therefore demonstrating nothing) that the Dream, being alone visible, alone matters, that light silences shadow. (Or perhaps the French—the Latin—temperament simply resists this arbitrary diktat of the German Master?) Art’s misfortune was that Wagner proved more musician than poet.

Second: Wagner synthesises observation and experience through Fiction.

But what manner of fiction? Historical fiction, though he pushes History back to the very borders of Legend itself. He conjures a specific time, a specific place. How worthy of Wagner it would have been to crown his work (after all his predecessors’ attempts to achieve dream through that old stratagem of temporal and spatial distance) with the total abolition of time and space, with the blossoming of Dream in its true homeland—timeless and place-less, not the forgotten but the unknown, not what lies too far from the solid ground beneath our feet, but that magnificent Country you won’t find on any earthly map.

Third and finally: though Wagner certainly graced the splendours of his music drama with the profound power of religious feeling, he has achieved little more than Balzac or any other in wedding Religion and Art through that inevitable return to the original unity of Truth and Beauty.

His thinking, more nakedly revealed in his theoretical writings than in his dramas58, admits no ambiguity: Wagner failed to recognise the divine calling of Supreme Religion that belongs to Supreme Art. He restricts Art’s pursuit of Truth to clarifying the divine truth within religion through idealised representations of religious allegory. But which religion does he mean, in our modern era when Criticism has shredded the Myths preserved and worshipped since antiquity? Contemporary Criticism forbids belief in the incredible, yet the modern spirit, like its ancient counterpart, hungers for sublime mysteries. How could Wagner not grasp that since religion survives for art only by shrouding its kernel of truth beneath ever-mounting layers of incredibilities, and since humanity now refuses to have these beautiful illusions submitted to reason, they must be offered to imagination ALONE! These incredible, marvellous elements that maintain truth at its proper distance—adorably remote, perpetually just beyond reach—belong to Art not as consequences, not as handmaidens to some Gospel, but as principles in their own right! Wagner’s position here might have sufficed in an age of religious triumph—but at present…

Then there are those who worked on a smaller scale but cut deeper: Edgar Poe and Baudelaire—that illustrious pair standing guard at the sacred Feast.

It’s old news now that Edgar Poe, barely glimpsed in France59, found there what proved the natural home for his glory—a glory left orphaned in his actual, thoroughly artificial homeland. He and Baudelaire share a spiritual kinship that deserves to be understood as indivisible.

Before Poe, this feeling for poetic consciousness was scarcely more than a presentiment; through him alone it gains its full rights, his entire work lending beauty’s authority to what logic could only hint at. This work survives only in fragments, left by life’s circumstances, yet divine fragments nonetheless. Here he could seldom display this consciousness directly through pure art, but rather obliquely, in pages where the most sublime Poet revealed only his less rare gifts. There he made Curiosity into an extraordinary passion. We admire him less for the flawless architecture of his Tales, for his perfect command of suspense building to its final burst, than for his profound grasp of that uncharted territory of nature and humanity which Victor Hugo had seen only in outline: the grotesque and the horrible. Quasimodo remains a vulgar monster, interesting only for his hump. Poe finds the grotesque in the soul, in the heart, and especially in the mind; he speaks to our souls, not our eyes alone. Everything becomes spirit in his hands, achieves spiritual synthesis. His fictions, though quivering with the most violent sensations, preserve a wholly spiritual character. His passions exceed humanity. His grotesque creatures are demons, his beautiful ones angels. And like humanity, he surpasses life itself, whether through sheer intensity of feeling or through death, beyond which he perceives an ardent, mysterious existence.

Let us grant him his due: he is the Poet of Love in Fear, Love in Madness, and Love in Death.

His creations preserve the singular quality natural to their exceptional atmosphere, which he explicitly identifies as one of Beauty’s laws. The Exception! Here perhaps lies Poe’s most telling feature, his richest contribution to art. Only through the exceptional can the new Poets achieve their lofty dreams of learned aristocracy and pristine beauty. And these exceptional, singular figures—Ligeia, Morella, the two pale denizens of the House of Usher—what passionate frenzy pounds in “their inert angelic breasts60“! This frenzy belongs to the Poet himself! Yet it never clouds his awareness, and through the most tangled webs of horror, madness, or fear, he keeps the unshakeable clarity of the Master who has tamed Chance. Death and Horror he gladly sets in sumptuous frames—a deliberate choice—where objects’ ironic life seeps through, where splendour hones anguish, where the heroes of sorrowful dreams watch their nightmares pull faces at them. The sense of the Exception, the Spiritual (singular) sense of Beauty in intensity, and the Lyrical sense of Science constitute Poe’s three most glorious claims to eternal admiration.

People ask how Science and Art will achieve the great synthesis yet to come? Pascal, Balzac, Edgar Poe, M. Villiers de l’Isle-Adam have the answer. Art will use Science as a foothold to secure firm ground, then vault over it on Intuition’s wings. Read Eurêka, that romance and poem, that sweeping religious, scientific and lyrical vision that makes Faust jealous. Poe singles out Melancholy as what is fundamental to Beauty. I sacrifice neither respect nor wisdom in observing that at the time Poe gave voice to his vision, this was indeed Beauty’s essential character. But his words, if merely echoed today, would ring false to his vision’s true intent. Life being the wretched thing it is, while Art still lacked the means to fully realise our dreams of happiness, it had to remain in mourning for the joys life withholds and Art could not yet conjure in dreams.

Poe never knew Wagner. He lived in that hour like the vigils before Christian feasts, when the Church demands every physical and moral suffering from the faithful, so that tomorrow’s celebration might blaze brighter against today’s shadow. But Wagner has spoken, and Science, coming to Art’s aid, offers miraculous means of realisation. Today Poe would declare that Beauty’s essential, fundamental character is Joy61.

Poe and Baudelaire were creatures of the same era.

Baudelaire has catalogued, as it were, our grounds for sorrow. Like some prince of darkness, he has drawn through Art a beam of black light. “He has laid bare the morbid psychology of the spirit reaching its sensations’ October; chronicled the symptoms of souls claimed by suffering, chosen by spleen; exposed the spreading rot of impressions when beliefs and enthusiasms held in youth have withered, when only the dry memory remains of miseries borne, intolerances endured, bruises inflicted by minds crushed under absurd fate.62.” His glory rests in “having managed, when verse served only to render the outer surface of beings and things, to express the inexpressible through a muscular, fleshy language that possessed, beyond all others, the uncanny power to capture with disturbing precision the most elusive, most troubled morbid states of spent spirits and grieving souls63.” He dedicated his sad vigil to blazing secret trails through the soul’s depths. He took the measure of evil, of artifice, and fell for them perversely, joylessly, like someone pronouncing his own damnation for love of Justice. Baudelaire is a sensualist sentenced to mysticism, alien to scientific explanation, adrift on the currents of modern vice yet watching them with an eye as stern as a Latin priest—a fallen priest, no doubt, all the sterner for it. Latin and traditional in his exacting moral taste, in his thought’s logic amid dreams; Latin and Roman in the squared force of his brief genius—not short, but concentrated—utterly assured, rich, dark, in his very poetics and especially his rhetoric, in the razor-sharp discipline of his expression. Baudelaire both discovered modern verse and plunged French genius back into its living springs, refusing it those illogical liberties that had been corrupting it. He distilled French Poetry into his verse and his prose—that matchless prose of the Petits Poèmes and the Paradis Artificiels! This mighty effort and the desolate object of his relentless vision left him incurably bitter. What a tragic and magnificent face this Poet wears! Look at him, not in the poor portrait from Les Fleurs du Mal64, but in the aged Baudelaire a late photograph reveals. That scornful mouth and those probing, judging eyes, perhaps without much interest left, but without pity either! Every vile thought reflected in that handsome face, like an endless vision of punishment. The hair still long and going grey, one side of the face mocking, the other rigid as death, the eyes wild, the lips clenched in disgust…

Flaubert, Sainte-Beuve, M. Leconte de Lisle and the Parnassians65, all have contributed, in formal terms, to a great literary revolution. Fundamentally, each has produced work of uneven interest, yet each, in its way, anticipates what is to come.

Whether languages ever reach a fixed state is an idle question. Every writer today fashions his own language to some degree. Yet I believe that for those more eager to articulate new things than to mint new words, it is infinitely precious that a man of genius should have dedicated his chief endeavour to achieving the most assured, most powerfully beautiful form of literary French—classical and romantic at once, both traditional and animated, perfect. This endeavour constitutes Flaubert’s achievement and his glory. To the first-time reader, this Poet seems to have created French prose itself, and to have created it as though from without, from afar, omitting to sign his page. Avoiding nuance for this purpose, he fosters the illusion that each thought, each idea, each sensation, each feeling finds its designation in a single, certain word. His gaze sweeps wide but remains somewhat general; he feels in a manner more extensive than profound. Sainte-Beuve, conversely, reveals his own failings, his inadequacy to high ambitions, forever speaking of himself, signing his every word, offering us the subtle analysis—which would be exhaustive—of his faults, his remorse, his intentions, his scruples, the whole resolving into a dense yet somehow weightless ennui, the tedium of a reasonable, mature mind determined to be neither the dupe of others nor of itself. With him, all is nuance. Ideas and feelings divide, scatter, and the desire to reach that primary, precise element—which perpetually eludes—draws the Poet into a delicious, bewildering vagueness of both soul and style. Someone has delightfully compared Sainte-Beuve’s sentence to a chorus of shades beside the black river, imploring the traveller to utter on their behalf the fateful word that must deliver them, which they have forgotten, which they seek in vain and which the traveller may never discover, yet which he is confident he knows, which trembles perpetually on his lips. This word is the mot juste—the word that does not exist, the one Flaubert wields with illusory and magnificent boldness, on condition that he remain within the universal realm of general representations66. Sainte-Beuve possesses that thoroughly modern desire to say everything. This mind steeped in the classics touches constantly upon the insufficiency of the education they have afforded him. At every moment he would invent new vocabulary, yet timid, doubtless prudent, he settles for creating verbal alliances through which he suggests what he wishes yet cannot express. His sentence—I speak of the writer of Volupté, not of the Lundis, where he becomes merely an exceptional literary journalist—takes pleasure in equivocal turns that are precisely the sole honesty of the artist in possession of delicate and subtle thoughts and sensations, his only “integrity”. It carries the echo of a gentle plaint that, discreet as it is, will never cry out. — Yes, the plaint of a shade, a lament that does not utter itself yet wishes to be divined.

From Sainte-Beuve dates the first essay in literary suggestion. He neither explains nor describes, yet knows how to make us see and feel. He achieves this even more distinctly through his verse than his prose. In truth, his verses are often curious rhymed prose—that Monsieur Jean, for instance, his most singular experiment. The very taste for detail brings about this unexpected yet logical result: In his case, the fine points of feeling overwhelm the fine points of articulation. All yields nothing. Everything is underscored. The poem, like an exceedingly fine, exceedingly ordered, exceedingly fluid fabric, has neither rents nor spangles. The subjects Sainte-Beuve deems worthy of his attention, subjects best served by attending to small matters, inertias, and tenderness, necessarily called for this form. It wears upon the reader, as do those subjects that bring it into play.

With greater force and intensity, either Sainte-Beuve would escape himself, become mere vapour, or he would arrive at that deliberately personal, nervous and liberated language which the Goncourt brothers have made their own. Sainte-Beuve wavers too much between Tradition and this need to express new sentiments in new forms67.

Thus Flaubert and Sainte-Beuve, each in his distinct manner, had recast French prose. What they accomplished for prose was achieved for verse by M. Leconte de Lisle, M. Théodore de Banville and the Parnassians68.

The absurd imitators of Lamartine, Musset and Hugo, and Hugo himself—that vague philosopher of Religions et Religion and L’Âne—had let Verse go slack: impoverished rhymes, hateful padding, makeweights and slovenliness. Verse in their hands had grown flaccid, limp, bodiless and headless, hollow yet bloated—it was amounting to nothing. They believed they filled it with witless cries they mistook for passion and platitudes they mistook for thought. Against this deluge of cowardice and nullity, M. Leconte de Lisle, with an unerring sense of the necessities imposed by the moment, set disciplined form, austerely beautiful, and moral impassivity. M. Leconte de Lisle is a great conscious artist, and his melancholy, elevated work bears the hallmarks of an imposing perfection. The finest among the younger minds followed his lead. For them, irreproachable form and dispassionate thought became rallying cries. The Parnasse, which stands as the symmetrical antithesis to the Romantic school, has rendered Art signal services. Some claim there was excess in their doctrine of Art for Art’s sake. I believe there was prescient clarity, and that the School’s sole error lay in not daring to pursue their principle to its ultimate conclusions. Indeed, that grand formula—art for art’s sake—transcended the Parnassians’ own conception. They confined Art to being scarcely more than Expression, and for many it amounted to nothing but form for form’s sake. Yet even so, such as it was, their doctrine was salutary and necessary. They reforged and retempered the noble Verse, rendered it worthy of serving genuine works, fit to undergo final and essential modifications. Is it not a telling spectacle, this Art of the nineteenth century in the aftermath of Romanticism? Whilst the final Formula evolves—the naturalist formula requiring neither numerous practitioners nor extensive time—the true Artists undertake a far more arduous and valuable labor: the refinement of Art’s instruments, Prose and Verse. Among these artists, one actually propels the Naturalist movement itself: Flaubert. Others include Sainte-Beuve, Messieurs Leconte de Lisle, Théodore de Banville, Catulle Mendès, Léon Cladel, Léon Dierx, François Coppée, Paul Verlaine, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Stéphane Mallarmé, José-Maria de Heredia, and Armand Silvestre. Yet beyond this shared endeavour, and concurrent with it, each of these artists devotes themselves to the completion of a personal work in which, admittedly, the artist-element prevails over the poet-element.

Flaubert and M. Leconte de Lisle stand as the last of the historical Poets. In their work, the scrupulous pursuit of truth, that “fidelity to detail” Balzac made his watchword, becomes, though scarcely to their credit, a tyranny. They remain bound to Fiction’s imperatives yet bring to them no fresh voice. La Tentation de Saint-Antoine and Salammbô, Les Poèmes Antiques and Les Poèmes Barbares belong to the same fictional order as Les Martyrs and Notre-Dame de Paris. The only substantive difference lies in their varying degrees of factual precision. Yet in form, in the sentiment expressed, and in their choice of subject matter, they effect a revolution. Flaubert and M. Leconte de Lisle cry out with less violence, more inwardly than their forebears, but their lament cuts deeper and springs from more authentic pain. They no longer pine over love’s sorrows. Their affliction strikes at the very core of their being, at the dread of knowing nothing, at

La honte de penser et l’horreur d’être un homme.

[The shame of thinking and the horror of being human.]

And remarkably, their lament—though it plumbs greater depths than the already passé Romantic complaint—proves far more controlled, aesthetically finer, possessed of a beauty that satisfies (perhaps unconsciously) half their souls’ hunger for transcendence. Through them, Art strides towards its sacred calling. Beauty that consoles through mere presence, or at least sustains the will to live—is this not already a Religion? As for established faiths, neither Flaubert nor M. Leconte de Lisle spare them much thought, least of all the so-called living religions, which seem long dead to their eyes. They make no attempt to reconstruct the machinery of a society ruled and inspired by great faith, nor to stage for us the noble contest between Christian belief and earthly love. To them, this Gospel lies deader than those it destroyed. It is to those ancient victims, rather, that they would appeal for answers, or to others the Gospel never even imagined. Saint-Antoine reveals a soul tortured by visions of Life’s Paradises; Salammbô serves as priestess to Tanit. M. Leconte de Lisle subjects Vedic Art and the religions of classical antiquity to careful examination. These two Poets brought modernity its most valuable gift: Art that draws from formal perfection the consoling thrill of a Religion of Beauty, and Thought that returns to its wellsprings to seek the metaphysical nourishment for that Beauty. Beyond this, Flaubert is praised for his “objectivity”, M. Leconte de Lisle for his painter’s eye for landscapes and beasts, and his stoic detachment. I maintain that Art is fundamentally and exclusively subjective. Impassibility was a truth that has become an error—a momentary necessity, nothing more. As for M. Leconte de Lisle’s creatures, their pulse beats no stronger than that of figures captured in oil. They are catalogued. The very techniques of description sometimes want for subtlety. Those elephants, for instance, that make the earth tremble, recognized mostly by the noise they make, strike one as rather stock figures. The vaunted fidelity to detail falls short in this instance. We miss that shuffling gait of the ancient, enormous monk dragging his sandals that so distinctly marks the elephant’s tread; that rhythmic, sacred sway of the massive head and trunk… Shift the angle slightly, and this philosophy of nothingness reveals itself as rhetorical posturing rather than serious reflection.

“M. Théodore de Banville belongs, through his genius, to the generation now coming into its own. While he finds solace for living in our prosaic and dismal age by recalling the Hellenic roots that ground our race, he has nevertheless felt and understood all our afflictions. Among our Masters, he wields the most vital and blessed influence upon the future.”69

To call M. Théodore de Banville merely the greatest living poet who has fulfilled his promise falls short. I believe Poetry itself animates his soul. How, one wonders, amidst this critical century, suffering its miseries like any other, in this land of censorship and academies, could a man of this time and place recall humanity’s true, pristine, primordial joy, stand against the relentless tide of convention, and not merely write or speak but sing (like those bards who went in company with the Greek host to Troy, rousing them for battle and soothing them after), yet in singing appear, lest he offend, to do nothing more than write or speak like his contemporaries. With a language of dead vocables, worn smooth as old coins beneath fingers idle for two centuries, how did he succeed in conjuring the blessed illusion of an endless cascade of fresh jewels? His soul, I insist, must be Poetry incarnate, which is why his eternal youth no longer leaves us in a state of bewilderment, nor his lyrical genius that plays with words, compelling them to trace harmonious, startling, meaningful arcs, so profound yet allowing itself to seem artless. The Poet of Les Exilés and Odes Funambulesques has rescued Parnassus from the potential absurdity the pomposity of its bearing nearly invited, and recognising that Melancholy cannot be Art’s final destination, has blazed the trail towards that joyous dawn where all shall be renewed. This single word proclaims his exalted station: Joy dwells in him! Joy in ideas, joy in colours and sounds, the supreme joy of Rhyme and Ode. M. de Banville has demonstrated in verse and expounded in his Petit Traité de la Poésie française that Poetry is intrinsically lyrical and Rhyme the quintessence of Verse. He has likewise affirmed and proven that Drama must be an ode in dialogue. Though certain contemporary innovators appear to have forgotten this, and though we must certainly nurture and advance the reform already achieved, forever liberating Expression further—within, naturally, its inviolable limits—I believe Integral Art will remain deeply indebted to the Master who first articulated these twin principles. Better than anyone, he has illuminated the relationship between Truth and Fiction, shown how life’s raw material must be enriched by Imagination’s conquests, and defined the dual calling of Art: to realise Dream through Life, to beautify Life through Dream.

“This double purpose: to make us forget Life while representing it still. For nothing can engage us that is not life, yet we cannot rejoice unless our troubles are magically dispersed and banished by almighty Illusion.”

And elsewhere, declaring the need to breathe spiritual essence into the objects of the artwork:

“No material object speaks directly to our soul, and our soul responds only to what calls to it without mediation.”

He understands that everything resides in Beauty, that a poem’s worth lies in its beauty. While he hasn’t explicitly declared that Beauty presupposes Truth, that mankind will one day allow the former to guide it to the latter, I doubt he would resist this notion. Finally, as much as Gérard de Nerval himself, though with greater self-command, M. de Banville has a genius for conjuring the marvellous, paired with the restlessness before the enduring miracle at the heart of life, as well as the worship of woman for the mystery she embodies as much as for the delights her beauty inspires70. He has felt the great tremor of the young generation that pushes for answers where previous generations had been content not to know. He understands that Art now roots itself in profound metaphysics. As witness who admires and comprehends, who knows these noble sufferings, this ultimate struggle between Man and Nature, he observes:

“No longer a chivalrous duel but earnest combat that he must wage against eternal Isis; he seeks not merely to lift her veils but to rend them, destroy them utterly, and bereft of his vanished Gods, to possess at least immutable Nature herself, sensing that from her these Gods shall rise again to populate anew the wildernesses of boundless azure and the mysterious gardens where stars spring into bloom.”

This is the Poet who has been called—and has allowed himself to be called—unthinking, simply because, as consummate artist, his verses touch thought only through the sounds and colours of the Symbol that embodies it. Let them chatter on, just as he permitted them to. We who understand, let us admire and love.

I believe M. Catulle Mendès is endowed with the gifts of a supremely great Poet. If he remains merely the most prodigious of artists, should we hold him, or his time responsible? The Parnasse, as we know, is his achievement above all others, born of his energy, his tireless activity, and his undeniable talent. Perhaps he has remained too loyal to the school he championed so brilliantly. Perhaps the very nature of his talent—so pliant, so multifaceted, so adept at mastering every technique—has prevented him from achieving that singleness of vision essential to unified work. He is without question the most brilliant of men, the most receptive and erudite of artists. He could not possibly be blind to Art’s ultimate destiny. Of this I am sure—he knows. Form itself, omniscient as it is, must surely have whispered all its secrets to him. Yet he does not serve these higher ends. He is content to write things—admirable past all doubt—that gesture towards an ideal suspended between past and future. His energies are spent on perfections that matter less. If this springs from indifference or scepticism, we cannot absolve him.

The oeuvre of M. Léon Dierx stands noble and pure. This Poet, whom success has scarcely courted (nor has he courted success), will endure, treasured above all by the young. His is a melancholic intelligence of Nature and her human echoes, an art of profound harmony from one who both feels and thinks. As M. Mendès so aptly puts it71: “I doubt there has ever lived a man more intimately, more essentially poet than M. Léon Dierx.”

M. François Coppée presents a most curious and appealing figure. One can hardly imagine the rising generation turning to him for the key to fresh inspiration. His work marks an ending. Yet it has merit, and he is right to trust in it. His vision is entirely his own, justified, though not supplied, by glimmerings from Hugo, from Baudelaire and M. de Banville, but above all from Théophile Gautier and Sainte-Beuve.

M. de Hérédia, whose talent is infinitely less subtle though more thunderous than that of M. Mendès, is likewise above all an artist. From dreams of gold and blood, splendidly theatrical, he fashions poems devoid of thought yet brimming with movement and colour, verses at once sonorous and vigorous.

M. Armand Silvestre—in whom the prose writer might eclipse the poet, that poet intoxicated with pure Lyricism—has written, particularly in his Paysages Métaphysiques, some of the finest verses I know. The very title of this section from M. Silvestre’s first collection reveals how this singer, who later let sensuality flood his work, possessed a true instinct for the new paths ahead.

M. Léon Cladel, Baudelaire’s disciple, remains the bard of his Rouergue skies and fields. The City taught him that in its eyes, the Countryside stands for an ultima Thule, and he sings the Countryside with the voice of a countryman who knows, with rustic shrewdness, how to present simple fruits to city-dwellers in ways that startle. He lacks the gift of verse, but this astonishing stylist has forged his prose into a true poet’s instrument, better suited, however, to conveying physical stirrings and exertions than sentiments, ideas, and thoughts. Yet, since he magnifies his actions and characters with epic intensity, one might say he crowns them with a heroic aura in the reader’s imagination.

To these last six Poets let us offer our disinterested tribute. They have been keener to work, on their own account, the veins already opened than to prospect for new ones. We salute these accomplished works as handsome monuments beside the road.

Finally, among the undisputed Initiators, I have reserved two Masters: M. Edmond de Goncourt and M. Barbey d’Aurevilly, who, despite their differing principles, have brought equally fertile consequences to Art.

M. de Goncourt’s genuine merits seem to me quite other than those he most wishes acknowledged. History reduced to deciphering century-old curios, the human document, initiating the modern public into Japanese Art—these form the most visible portion of his work, not the most substantial. M. de Goncourt has grasped, with greater acuity than any who came before, what we must term (for want of a better word, since linguistic tradition inevitably fails when addressing what most specifically distinguishes today from yesterday) Modernity. He has perceived how the uniform mask science imposes on nature wherever it directly touches humanity drains the human element from things, while things themselves reclaim, in threatening silence, their autonomous life, alien to a humanity thus vanquished by its own triumph and powerless to reclaim its ruins as they revert to nature. He has observed how in society, whose members, sacrificed to the collective, also bear this yoke of uniformity, certain abominable or exquisite exceptions rebel against the decree to wear a single mask, concealing beneath it their true face: their Physiognomy72. Through his paramount attention to human physiognomy, M. de Goncourt has achieved the synthesis of the human soul. This matters far more than his pursuit of human documents, which tend to distort the whole through magnified detail rather than establish what the Naturalists pedantically call “the great inquiry.” Such an approach often reduces books to mere inventories. He has tracked across this ever-shifting physiognomy its manifold and elusive expressions: he has captured the uncapturable. We know, in this mode, the truly extraordinary pages in Madame Gervaisais, in Renée Mauperin, in La Faustin and in Chérie, which have seduced countless imitators into efforts that ended in failure. This pursuit and conquest of the elusive naturally led M. de Goncourt along paths Sainte-Beuve had already traced. But M. de Goncourt has ventured incomparably further—to the ultimate boundary, I believe. Here, for the first time, we witness the writer fashioning from whole cloth “a personal language.” I am aware of every objection to this enterprise of writing in a private idiom that readers must learn to properly comprehend, and I know that all such objections, to use Molière’s phrase, count for nothing against this is beautiful, which is the verdict any enlightened sincerity must give voice to. Critics contend it robs the work of enduring clarity. But this complaint is childish when we consider that time itself forges for each century a distinctive language the next cannot grasp without study. The writer may claim any liberty, provided his particular language bows to the native genius of the tongue and to the genius of those dead languages that shaped it73. M. de Goncourt’s language meets both demands. Through modernity, through the life of things (though placed in service to human life and physiognomy), through personal language, M. de Goncourt belongs to the new generation. He stands apart from it in his indifference to divine mysteries. One might suppose that too scrupulous an attention to details—however significant, however reflective of the whole—suppresses in him that higher imperative to marshal all mental energies towards a single end. M. de Goncourt lacks the religious temperament. Beauty captivates and gains mastery over him primarily by piquing his curiosity, but when curiosity kneels, it does so to see better, not to worship. M. de Goncourt embodies the Modern Spirit in whom the scientific puff has already extinguished the mystical flames of Revelation without yet kindling the equally mystical fire of convictions won through science. He searches, he doubts. Perhaps he lacks even the will to believe…

M. Barbey d’Aurevilly, on the other hand, stands as the gallant defender of ancient faiths. Here is the modern mind that has kept faith with the Gospels, admitting what Science holds as opinion only when it passes Gospel scrutiny. He delights in mocking Science, daring it to explain the mysteries it can merely record. Yet he too feels the great commotion of our age, and he too, when reading faces—scarcely concerned with the arrangement of features—becomes utterly absorbed in this tragicomedy of tears and laughter. Where M. de Goncourt observes a mutual influence between social environment and physical constitution with incurious curiosity, M. Barbey d’Aurevilly sees God instead. His vision may not be surer, since he lacks due respect for Science, yet it is at least more illuminated. He knows that beyond these dense shadows lie superhuman radiances. The great drawback of this personal God is that it becomes a word spoken too soon, a word carrying above all the oppressive weight of a prohibition, a door barred against the Beyond. And this door, however magnificent and imposing, still graced with mysterious Gothic carvings, the Modern Spirit has resolved to break down, to press onward, to peer deeper into the vast forbidden Beyond. Such impiety is itself pious. Perhaps it even lends a grand mystical character to the appalling vandalism of the Revolutionary crowds. Those people had no notion what they symbolised. Theirs was the invincible, irresistible thrust of the human soul towards the God it desires, conscious or not of its desire. M. d’Aurevilly shows no mercy to this love that knows not its own name. Yet this ruthless severity has furnished him with the solid cornerstone that makes his work so commanding. From the summit of this outmoded mysticism, as if retrieved and blackened through long centuries, the Poet casts his gaze about without permitting any disturbance to affect him and, reducing all to his single thought, creates his own synthesis of the new age according to laws of ages past that still ring in his ears. He too understands the marvellous nature of things, possesses the keenest sense of modernity, holds the secret of Physiognomy and commands his own distinctive voice, one among the finest to be found in any literature. An eloquent and subtle voice, poetic, austere and impassioned. Think of carvings in an ancient wall that crumbles, whose ruined sections nevertheless stand by enchantment and will never fall. So this voice appears: dark, with sudden blazes of light that dominate. That definition of Hell—”Heaven hollowed out!”—captures its quality. Habitually excessive, cutting, brittle and wounding, this is the discourse of a sadistic dandy who knows equally how to grow languid and tender, to murmur, to smile. This voice seems always to describe, yet it almost always evokes instead. It leaves behind something like a taste, a wound, an affront, a dialogue overheard in darkness. Crimson, saffron, pearl-grey: this may be literature’s most extraordinary monument. Here the voice of the Past still thunders, vexed by the Present’s “Buts” and “Yets”, and rather alarmed by the conclusive “Because” that the Future stands ready to pronounce.

With this great writer we conclude our consideration of those who gave rise to and shaped the new Art. We shall yet discover their influences concentrated and crystallised, and if not fully realised, then at minimum gesturing toward ventures the past could never have imagined. We can detect these now in the Poets who remain to be briefly discussed, though in truth, what have I done until now but discuss them already?

Surely no one would contest that we must take stock of all this century’s greatest minds to comprehend the work of M. Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. In him, Mysticism and Science converge to secure the victory of the former through the latter. Fiction’s fabulous virtue—though it remains, alas, tethered to time and place—nonetheless liberates it into Dreams of pure human philosophy, where science and the chosen moment serve merely as occasions, without any longer the subsidiary concern for faithful reconstruction of historical fact or meticulous description of the contemporary moment. Consummate mastery of form, far from being that accursed compact Baudelaire describes between artist and instrument, binds all Art’s external resources—of a musical and plastic nature—to the immediate service of embodied thought. His horror of life’s degradation, though this Poet numbers among those life has most brutally treated, finds its note of bitterness only in the irony of a luminous soul, withdrawn in advance and forever into its unshakeable certainties—an irony that turns away from evil’s spectacle rather than pausing to denounce it. The sense of life’s wonder, made base though its essence brims with surprise and delight, emerges both intuitive and reasoned, served by a mind sovereign in abstraction and imagination alike, the mind of a religious Thinker, a mystical Metaphysician, dedicated to magnifying the complete work of Art. The regal nobility of this mind and sensibility, curiously allied to nobility of birth, endows genius with a magnificent accent of eternally youthful pride and makes it the exceptional soul itself in love with the Exceptional. Every book Count Villiers de l’Isle-Adam has thus far given us portrays only beings of rare human essence, made more truly and fully human by that very rarity. — Mind and work authentically synthetic.

I should like to offer some reflections that will qualify our admiration without taking anything away from it. This irony, seeking to avert the sight of evil, which M. Villiers de l’Isle-Adam brandishes—truly!—like a weapon that would prove deadly were he not generous and Christian, springs less from the usual source (the gulf between Life and Dream, between mankind and genius, between error and Truth) than from the particular circumstances of the age in which the Poet reaches his prime. He has repeatedly found himself compelled to deploy this irony against the presumptions of Science run mad, so intoxicated as to deny Mystery itself—a more temperate Science would have left the Poet both grave and glad. Doubtless it is also because this hour of wisdom, which will be the hour of gladness, has not yet struck that this Poet keeps his Melancholy so close to his heart. Perpetually he summons “the phantom of a mysterious woman, queen of pride, dark and fierce as the night itself, already twilit with glints of blood and gold upon her soul and beauty.”74 — Finally, we come to the Monument, the work’s overarching unity. This conception may have come to him in youth as he stood on his native Breton shore contemplating his future, listening to the sacred sounds of organ and ocean. Yet the mature artist has not brought this vision to fruition, and again, perhaps for the same reason.

Naturalist influence has touched M. Villiers de l’Isle-Adam only slightly, and then solely through Balzac and Flaubert. What was still-obscured irony in Flaubert has become, in Villiers, the Poet’s ultimate and most refined expression of astonishment at the World’s unworthiness. His chief inspirations are the Romantics and the Classics, along with Nature herself. More specifically, he turns to Chateaubriand and Goethe, to Pascal and to Shakespeare.

M. Joris-Karl Huysmans would stand utterly outside both Classicism and Romanticism were their echoes not still reverberating through Flaubert and M. de Goncourt. First seduced by Naturalism, he caught from it that dangerous malady, by which I mean, the hatred of ideas. His salvation came through a gift he shares with M. de Goncourt and M. Barbey d’Aurevilly alone, though neither of the latter two has it to the same degree: Modernity. M. Huysmans commands the intelligence, the taste, the love—intricate, alloyed, tempered and refined by hatred—the feeling, in sum, for modern virtues and vices, for the contemporary atmosphere and cast of minds. And as Modernity embraces the whole man, M. Huysmans, to render it, has had to ascend to a comprehension of all Art. Hence, having débuted with En Ménage and Les Sœurs Vatard, he has achieved that curious À Rebours, where his spirit still hovers between the realities of appearance and the realities of Dream, examining the latter from within the former as a curious, invested observer who dares not declare his preferences and treats these new Beauties as oddities rather than revelations. In En Rade the vacillation persists: Dream and life run parallel, and Dream consists largely of dreams darkened by memories of living. Yet against that life, that execrable life, never has a Poet voiced his revulsion with such cruelty, such magnificence. Here is mortal rage, the more terrifying for its justice, the more bitter for its exclusive fixation upon objects of horror, fury and disgust. No one can long bear such inner torture, particularly if they have already tasted Beauty’s consolations. And M. Huysmans frequents those literatures that strain against their boundaries and worships certain supreme artists, notably M. Gustave Moreau. On this painter, À Rebours contains some of M. Huysmans’s finest pages, passages that wholly vindicate M. Francis Poictevin’s dedication of Derniers Songes to J.-K. Huysmans, “that writer so penetrating and so magnificent.”

Madame Judith Gautier may well be, among this generation, the soul most singularly poetic, most proud, and—beyond all passions, dwelling in her realm of dream—most tranquil. In her work too, Fiction, though it tarries in named lands at specific dates, retains nothing of history or geography. Fiction becomes the atmosphere of Beauty, and Beauty becomes the spirit’s religion. I think I do not err in suggesting that this Poet’s soul has room for nothing but the Dream of Beauty. And this soul, within that Dream, discovers both its joy and its creed. Must not God be that which is most beautiful? Can Truth be anything but supremely beautiful? Here, granted, we return to general ideas, yet these are scarcely ideas at all. Le Livre de Jade is pure graceful beauty; Iskender is pure beautiful form. What makes Madame Judith Gautier strike us as a more complete, more unified poet than, say, her father Théophile Gautier? She possesses in her dream greater freedom, greater intensity, greater simplicity. She reveals to us, whether knowingly or not, in those beautiful forms she cherishes, symbols of everything we most desire in charm and truth. Whether she lacks intellectual depth I cannot say: she has taken care not to let us find out.

Much that I have observed about M. Villiers de l’Isle-Adam holds for M. Paul Verlaine, with this crucial distinction: prose serves as the vehicle for one, Verse for the other. Yet “in no poet do those two mighty currents that sweep the whole of modern art from Goethe and Chateaubriand to ourselves converge more decisively. At times these currents appear to diverge, but never for long: mysticism inhabits the Fêtes Galantes, sensualism pervades Sagesse. And Verlaine’s modernity lies precisely in this fusion of twin inspirations. When the moment arrives to cast his thought in artistic form, the conflicting impulses of his life toward purity and toward pleasure unite in his endeavour. The intensity of this union sets him apart from all the Moderns in this respect, and he owes it surely to his raw vitality.75.” For him, Fiction holds no appeal. He draws instead, and always, upon the eternal elements of Life itself.

“Because Verlaine embodies an intensification, an exacerbation of modern man, he has managed—consulting no documents save those of his own fate—to erect a monument of work that is both deeply personal and universal to us all; a work that, its hero gone, will grow ever more objective and resound as the most profound cry of the modern human soul. Yet he required exactly this intensity and this simplicity to reach so splendid a goal. With only his passions for artistic material, had he been more artificial or slack, he would have merely heaped up ruins without unified design, like most of our French poets. His vital instinct rescued him—that victorious Instinct which has not simply dominated intelligence but miraculously absorbed it, spiritualising itself toward intelligence whilst materialising intelligence toward itself, realising (etymologically speaking) the Ideal, ingeniously pursuing it afterwards, without ever letting imagination be snared by any mirages save those of life itself, painted as they are by chance across the screen of our desires. The poet has certainly struggled against this law, yet ultimately he yields to it, and his life’s drama has furnished the necessary painful atmosphere for his work’s drama: that elemental duel of dream and life, of spirit and flesh. How this living arena of combat suffers or exults with each contestant’s successive triumphs, which is to say, what constitutes the deep truth of modern sensations, how mysticism and sensualism divide between them, in our age, those souls not irrevocably claimed by pure thought’s horizons. To these questions Paul Verlaine alone has provided answers76.”

As with M. Villiers de l’Isle-Adam in tales like Akédysséril, we must note Wagnerian influence on Verlaine in poems such as Crimen Amoris. Through his remarkable Romances sans Paroles, he burst the constraining fetters with which the Parnassians had shackled Verse. Sainte-Beuve held the seeds of this revolution. Yet how tentatively, with what paralysing anxieties he advanced, and how he neglected to conceal his working methods! Verlaine shows no such marks of labour: Poetry takes wing and casts its spell. “Verlaine might recognise himself in M. Taine’s observation: ‘Form seems to dissolve and vanish. I venture to say this is what defines modern poetry.’ And mark this well: through his genius’s bonhomie, through his simplicity’s absolute sincerity, Verlaine transforms his verse into something airborne… windscattered… weightless and unposed… an art where form truly dissolves to reveal, in all the harmonies and shadings of their profound reality—almost beyond, almost despite language—those feelings or sensations evoked with such gentle-wrapped power. Thus he establishes the true distinction between verse and prose: verse being fundamentally synthetic, the musical and pictorial synthesis of what must be suggested, whilst prose, analytical save in special cases, whether symbolic or direct, breaks the object down into constituent parts.

Verse remains Verse for Verlaine, an untouchable, quivering entity whose protective armour he learned to forge from masters of the craft like Leconte de Lisle, Banville, and Baudelaire himself. Indeed, some of the most celebrated alexandrines quoted twenty years hence will come from Sagesse. Yet far more audaciously than Sainte-Beuve, pursuing the same end but with keener modern sensibility, he renders verse pliant, articulate when needed, according to the shades of feeling demanded and according to new logical principles—logical in him alone. Enjambment becomes both essential and deeply harmonious, though secondary to the shifting pulse of the caesura, the alliterations marking and measuring the rhythm, the assonances that deliciously disturb the verse with minor echoes whilst rhyme’s major brilliance—its horn-call glory—loses its harsh dominance, alongside those limping metres whose symmetrical asymmetry adds another harmony to this supremely artistic disorder. These techniques, deployed with a Master’s unerring touch, enabled Verlaine to accomplish what Sainte-Beuve attempted but, lacking either the means or the touch, abandoned early—a poet dead in youth. In time, Verlaine’s verses will command the admiration we reserve for the old masters’ canvases, where we marvel to find yesterday’s discoveries and tomorrow’s innovations brought to perfect fruition. Like those masters, he has penetrated directly, with that innocent intuition which complete knowledge recognises as its peer, straight through to things’ essential nature77.

Messieurs Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Huysmans, and Madame Judith Gautier command prose alone. M. Verlaine writes exquisite prose, to be sure, yet verse remains his mother tongue, the medium in which he has cast his only truly significant artistic enterprises. — One Poet wielded both prose and verse: M. Arthur Rimbaud. Within him resides, in M. Verlaine’s superb phrase78 (and we owe our knowledge of him to Verlaine) “the empire of splendid force.” Le Bateau Ivre and Les premières Communions79 stand as peerless miracles, each in its distinct genre. Absolute command of Verse’s secrets, music and painting, profound metaphysics and burning life—all are his.

Then suddenly, he appeared to abandon verse for prose, creating magnificent fragments: Les Illuminations, Une Saison en Enfer. His prose is too heavily infused with the genius of his verse. What results is still verse, merely liberated from measure and rhyme, surpassing even the rhymed verses it seems to invoke. Prose and verse have not yet managed to forge the necessary alliance or unite their forces toward a single, total effect.

— This is the union M. Stéphane Mallarmé aims to accomplish. Concerning the work of a poet who, by his own account, stands “barred from all participation in beauty’s official pageants,” I shall betray no secrets. That this work remains unknown would seem to prohibit naming Monsieur Mallarmé alongside those who have delivered books to the world. We must remember not to mistake for his true work those admirable poems in verse and prose scattered through journals and reviews. They are mere provisional sketches. I leave vulgar criticism to its buzzing and observe instead that without delivering “books,” M. Mallarmé has become, insofar as the word carries any meaning in our day, renowned. A renown, admittedly, not won without provoking laughter from the press both high and low—the guffaw of stupidity—or without providing public and private stupidity, whether pompously official or busily officious, the ready opportunity to parade its baseness when confronted by an approaching marvel. Yet this clamour gradually dies to a tentative murmur, half wonder, half reverence. Significantly, the younger journalists now affect to display admiration, though they are no better or worse than their elders. Unjust and insulting as this may be on their part, the shift is significant nonetheless.

What do we find here? Something perfectly natural and perfectly magnificent. Despite their present revulsion towards Beauty, and particularly towards Beauty’s innovations, people have grasped, involuntarily, incrementally, the force of authentic authority. They have grown—they themselves, even they! —ashamed of their witless laughter, and confronting this man whom no laughter could disturb from his contemplative serenity, their mockery has fallen silent, yielding in turn to silence’s divine contagion. Even to such people, this man who printed no books80 of personal art yet whom everyone called “a poet” became the Poet’s very emblem, one who strives to draw as near as possible to the Absolute. And for us Poets too, such is Monsieur Mallarmé. He stands as Art’s living conscience, the exacting Master we long to satisfy.

I stated we must not take the published poems for his work. Through them he has demonstrated, as it were, that he could pile up books like anyone else, books that open doors to every academy and earn the tears or applause of a public, small and select though it be.81

Then, through his silence, he declared that along this road of an art already graced with marvels, he felt no compulsion to do more than suggest significant innovations in detail, since, given the present condition of minds, or perhaps not yet having achieved his own definitive mastery, he could not bring forth the unprecedented work of art he means to create. This deliberate abstention demands a response from us, all the more so should adverse fortune deprives the endeavour of support. Our respect, or rather our reverence, is the only fitting one.

Thus, it is through the future his printed poems hold within, through rare theoretical pieces (notably the monthly Notes sur le Théâtre the Revue indépendante ran from December 1886 to July 1887), and through conversations where listening becomes joy itself, that Monsieur Mallarmé proves to be the Poet whom the living Future seeks out above everyone else. Many ideas82 that dwelt half-formed within us have found their life in this Poet’s kindred thoughts: on Art’s essential meaning and sacred office, on the true laws governing Poetry and Verse, on Theatre viewed as the supreme celebration of Art and synthesis of all the Arts, and on that vital fusion of Verse and Prose conspiring towards a single effect.

The achieved experiments in literary synthesis, or those whose design at least announces itself, would be, barring unlikely oversights, properly confined to this inventory. It seemed worthwhile to present them together, in the accompanying schema, which reveals more clearly than any commentary the bloodlines and affinities between minds.